Writers: Anne Frank, Ari Folman

Artist: David Polonsky

Colorist: David Polonsky

Letterer: David Polonsky

Cover Artists: David Polonsky, Kelly Blair

Editor: Ari Folman

Publisher: Pantheon Books

It’s astonishing that arguments begun by people with dubious motives in the 1930s and 1940s continue to have currency today. That frightening reality is, ironically, a perfect answer to the question: “Does Anne Frank’s story still matter?” On the one hand, it’s easy to dismiss a graphic adaptation of what is already a well-known document as merely a commercial attempt to reach a new audience. On the other, it is a reflection of not just how changes in reading habits prompt revised editions, but how a message may gain potency only through the power of repetition.

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation couldn’t have been an easy task for Ari Folman or David Polonsky. They certainly had the credentials — Folman wrote and directed the animated documentary Waltz With Bashir, while Polonsky was its art director — but creating a version of a book that was already translated into 70 languages, read by over 30 million, and subjected to many adaptations, revisions, and editions, would have been daunting for anyone.

What they did have on their side was artistic license, allowing them to select portions of the original text that worked best for the medium while maintaining the overall tone of what is, at heart, the diary of a teenager struggling to cope with an extraordinarily traumatic period of her life. To do this in a mere 149 pages, using visuals to say more than words can, leads to some natural omissions but also serves to highlight particularly poignant moments that don’t shine out in the original text.

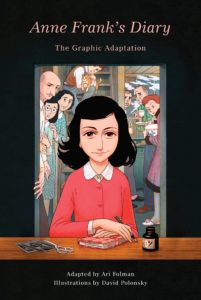

Even the cover, for example, with Anne staring out at the reader, her face revealing nothing, the seven occupants of her “secret annex” staring out at her, offers a lot of information to those who choose to spend time seeking it. Her desk holds a closed diary, a bottle of ink, and a pair of scissors placed over two photographs. There is tacit acknowledgement of her role as a memoirist, and the occupants of the annex look not just at her but at the reader, implicating us in how their personal histories unfolded.

It took a long time for Anne Frank’s diary to be published without publishers and editors bowdlerizing it to suit their personal agendas or perception of what their audiences would be comfortable with. The nicest thing Folman and Polonsky do is focus on the authenticity of what is Frank’s adolescence. It’s why her relationships with her mother and sister, and grappling with puberty, get more space than themes that traditionally occupy what we call “Holocaust literature.”

The diary itself, written from June 12, 1942, until August 1, 1944, was meant to be a source of comfort for Anne, and the graphic adaptation conveys that in a number of interesting ways. An entry on her desire to “lead a different life from other girls,” for instance, is depicted with an amusing illustration of her as a published author standing before a wall of famous magazines featuring her diary on their covers. It’s the kind of daydream any young person would have, and helps us separate the girl from the perceived victim. Elsewhere, Polonsky bases his illustrations on original photographs, reminding us constantly that all of this happened to someone very young, caught on the wrong side of history through no fault of her own.

The first English version of The Diary of a Young Girl appeared in 1952, around five years after its publication in German as Het Achterhuis or The Secret Annex. A month before she turned 15, Anne Frank expressed a wish to be a journalist and a famous writer. This edition is only another bittersweet reminder of the fact that she accomplished both goals.

![[REVIEW] A DAY OF JUDGMENT IS AT HAND IN ‘MIDNIGHT WESTERN THEATRE #2’](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/E66AB151-D25F-4691-B7F4-636734C82EE8-150x150.jpeg)