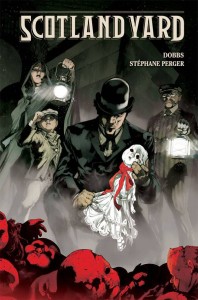

Written by Dobbs

Art by Stephane Perger

Review by Billy Seguire

Everybody loves a spinoff. Especially when it’s dark and gritty. Even still, taking the minor players out of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s universe and putting them up against creations approximating Bram Stoker is a gamble that demands a heady commitment. Scotland Yard succeeds in combining these concepts through clever world building and brutally visceral, unflinching art. The result is something akin to True Detective without the personal drama, a slow-boiling “true” crime with the themes of a society in transition persistent throughout. While there are aspects of Dobbs’ writing that keep it from being a perfect work, the well-worn Victorian backdrop gives Dobbs and Stephane Perger carte blanche to unleash a madness that overtakes the story with its vicious intent.

Everybody loves a spinoff. Especially when it’s dark and gritty. Even still, taking the minor players out of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s universe and putting them up against creations approximating Bram Stoker is a gamble that demands a heady commitment. Scotland Yard succeeds in combining these concepts through clever world building and brutally visceral, unflinching art. The result is something akin to True Detective without the personal drama, a slow-boiling “true” crime with the themes of a society in transition persistent throughout. While there are aspects of Dobbs’ writing that keep it from being a perfect work, the well-worn Victorian backdrop gives Dobbs and Stephane Perger carte blanche to unleash a madness that overtakes the story with its vicious intent.

Scotland Yard is built around the character of Inspector Gregson, an intelligent policeman originally appearing in four of Conan Doyle’s stories alongside the Great Detective himself. Following a botched prisoner transfer that leaves him disgraced, this version of Gregson is transferred to Scotland Yard’s Black Museum, something akin to a period X-Files, detached from the rest of the department. It is here the character is surrounded by a world influenced by both the fiction and history of the era, interacting with figures like Doctor Seward, Renfield, and the Elephant Man alongside Holmesian staples Wiggins and Lestrade. It’s the type of story where I felt determined to keep googling each new character as they were introduced in order to understand from what page of Victoriana they had sprung.

The book is divided fairly equally between two cases, with Gregson and company tracking two separate men who escaped custody at the beginning of the story. There’s no grand unfolding plan to their crimes, just pure unvarnished ferocity and a lust for death. As said within the book, the villains are “modern monsters who do not fit the pattern of our criminal profiles”, and if nothing else, the book continually emphasizes this theme of transition. Perger’s London is visually transitioning to a factory city at the dawn of the industrial revolution. Scotland Yard transitions its own habits, as Commissioner Fix hands Gregson his pistol in the call for Inspectors to now be armed in the face of this new breed of villain. And finally, the book highly emphasises Bram Stoker’s role in transitioning fiction through the publication of his novel Dracula, a core text on which much of Scotland Yard’s lore is based.

The story progresses with Victorian detachment, but without the heart of mystery that made Conan Doyle’s stories so effortlessly engaging and intriguing. Present instead is a carefully building dread that asks more from the reader. Unfortunately, the driving forces in that dread are all malice, no motive. In prose these actions could be deeply explored, but something about the comic medium in this story seems to preclude it. When we do get a motive, it’s told through flashback, not exploring that motive through our protagonists deftly analyzing a character’s actions. It doesn’t play towards the reader’s expectations of a mystery when compared to something like Alan Moore’s From Hell, a series that strives to capture a similar tone and atmosphere and does an arguably better job of making the audience uncomfortable while still leaving them guessing until the pieces all get put together.

Meanwhile, Perger’s art keeps your eye lingering on truly horrific visuals. There is some sickening imagery within this book, though ungratuitous in keeping with the tone, and it’s clearly something that was relished in the construction of this dark authorial mash up. There’s not a bad page in the book, with Perger bringing subtle character expression and beautiful, realistic representations of anatomy to each scene. Muted visuals consistently emphasize Victorian London’s old world fog and grime. Showing an inventive use of colour, several monochromatic sequences bring to mind the atmosphere of black and white horror films, intelligently visualizing the intended feel and evocation of the writing.

There’s an impressive understanding of how to use the formal construction of the page to create a subtle narrative experience as well. A scene with Gregson waking up in a hospital for instance, groggy with a head wound, finds the comic losing its outer panels in place of letting the watercolours fade out, giving an uneasy dreamlike quality to the conversation between Gregson and Ms. Faustine Clerval in her introductory scene. In another sequence, the regularly straight laced and orderly panels give way to crooked, unevenly drawn lines when shifting to the perspective of an unhinged villain.

Dobbs’ finale, to tease it only slightly, encapsulates the whole gruesome affair, with Renfield embracing himself as full vampiric muse in an orgy of blood and violence against the movers of the book’s plot. It’s only undercut by the remnants of his humanity left slipping through, which at this point is something of a disappointment to see the character be anything but sub-human. The full transition here would have worked better with Dobbs’ intended themes, but falls flat due to Renfield showcasing his human impotence, hurling insults at Faustine Clerval like a common thug in a scene which just makes me wish we could see one instance of a villainous reveal without calling a woman a ‘slut’.

VERDICT:

Check It Out. The highlight of Scotland Yard is the dark perspective of Doyle’s world as witnessed through Inspector Gregson. The “true crime” narrative provided something of a stumbling block in my expectations of a mystery, especially with a title like Scotland Yard. Yet Gregson isn’t Sherlock Holmes. The style is rightly different from those stories and allows the book to stand on its own. Bringing Bram Stoker himself, Carfax, and Renfield into the plot enhances the morbid realism and really gives what might have otherwise been considered a footnote a substantial hook. Their presence elevated the story enough for me to keep going through my concerns and I’m ultimately glad I saw it through. I’m still thinking about the actions of the story, and I’m definitely curious enough to be interested in the release of some of Dobbs’ other works in similar collections if Dark Horse finds this release to be a success.

![[NEWS] ‘AFTERPARTY’ GETS A HALLOWEEN RELEASE DATE](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Afterparty-poster-150x150.jpg)