For a fair share of us, Comedy Central is a staple of our television viewing diet. Whether it’s staying up late to catch The Daily Show, or spending a lazy Sunday on the couch watching the classic Young Frankenstein, Comedy Central has fueled the comedic itch for many a fan. But how did a station solely focused on comedy get off the ground and become a ubiquitous part of the modern comedy nerd’s existence?

Enter, Art Bell.

Bell, a relatively junior employee at the time, defied odds and successfully pitched the idea of a 24/7 comedy network while he was at HBO in 1988. His work in founding, programming, and branding Comedy Central not only helped make comedy accessible as a whole on a national scale but also helped bring cult classics such as Mystery Science Theater 3000 to the forefront.

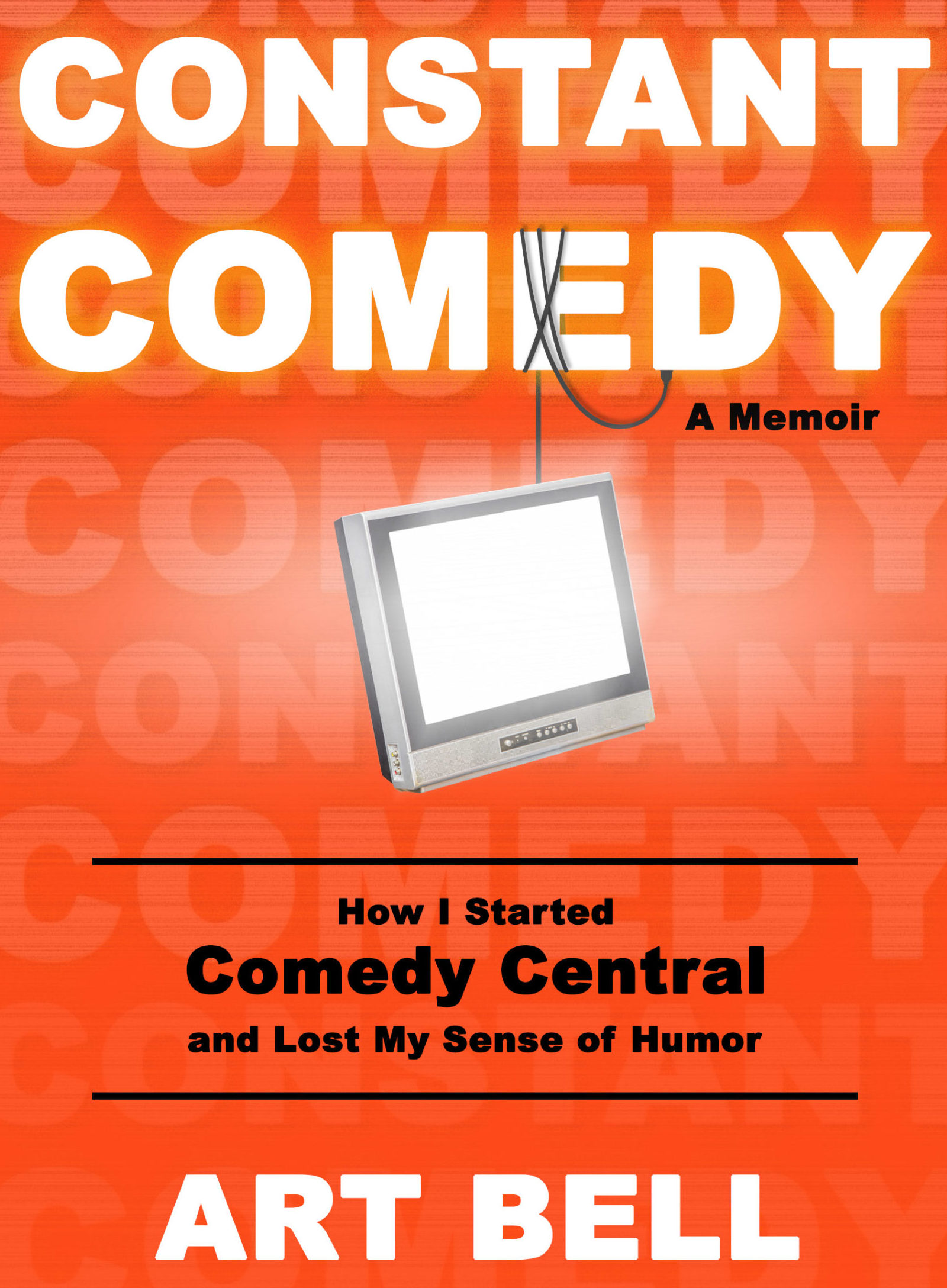

Releasing on September 15th, Constant Comedy: How I Started Comedy Central and Lost my Sense of Humor is Art’s memoir exploring Comedy Central’s unlikely creation, the early days, and how it became a staple in the television pantheon. Geek’d Out was lucky enough to sit down with Art and chat about the early days of Comedy Central, what makes a good pitch, and the value of classic comedy.

You were fairly young career-wise when pitching The Comedy Channel (Comedy Central). How exactly did you land the pitch? 24 hour networks were still relatively new at that point.

Art: The idea came to me, strangely enough, around the time I graduated from graduate school. It was really motivated by my passion for comedy. You talk about Geek’d-Out; I was a comedy freak as a kid. I listened to Robert Kline albums, George Carlin, and Bill Cosby albums. All those albums were all around me and Lenny Bruce. I had a fascination with Lenny Bruce, who was as you know is a breakthrough comedian, because he told it like it was and got arrested for it several hundred times. He set the course for stand up for some time to come.

Even outside of standup comedy, I was fascinated by comedy in general. I had read a ton of National Lampoon. We read it cover to cover and backwards when it came out. It was basically our blueprint.

Then, I eventually got to college and did a little performing, but I knew that I wasn’t going to be a performer. But I did get the idea for a 24-hour channel around the time. There was an all-news channel, all documentary channel, and an all-sports channel, why not an all-comedy channel? I thought it was the world’s most obvious idea, and apparently it was not. People stayed away from it.

As luck would have it, I ended up pitching the Chairman of HBO accidentally, and, incidentally, he thought it was, “Yeah, go and see if you can figure it out.”

Filling up any television station with content, let alone a 24/7 comedy station, is pretty demanding. In the early days, you were pretty much starting from square one programming-wise. How did you do it?

Art: We didn’t have a lot of licensed stuff. The concept originally was to have a lot of “clip programming” and have shows where comedians were throwing to comedy clips culled from movies, television, stand up routines, anything we could get our hands-on. To make a long story short, we got sign off from all the professional guilds to do that on a promotional basis, meaning for free as long as we credited them, which gave us access to a huge amount of comedy, as you can imagine.

Several weeks before we launched, one of the guilds, the Director’s Guild of America, called and said, “We changed our minds. The board rejected the idea after all, and so you can’t do it.” You can imagine my enthusiasm for that call. So, we had to really retrench at that point. Whereas we had thousands and thousands of clips prepared to go, now we had hundreds of clips, if not tens of clips. We had nothing, so little programming.

One of the things that I point out in my book, Constant Comedy, is that feeding this comedy maw day after day, especially at the beginning, was ridiculously difficult. So, you know, we obviously repeated stuff. And in the early days, you don’t have a lot of viewers, so you can get away with repeating stuff as your audience grows.

Interestingly, despite the fact that, in the first several months of the channel’s existence it was roundly panned by some people in the press, we developed an audience. We started to hear from advertisers that their kids were watching it, and we started to hear from cable affiliates that their kids were watching. You know teenage kids, young men were basically watching it. So, we did get an audience from it.

On top of that, we had one cult hit from the get-go content-wise, and that was Mystery Science Theater 3000. In our darkest days, probably three or four months into the channel, when we had to show up to a convention and everybody said, “Well, we got nothing,” I said, “No, we got Mystery Science Theater 3000, and we’re gonna put that all over the place as our hit,” and that’s what we did, and that kept us going.

Speaking of, from what I take it, MST3K was fairly small before Comedy Central. How did they come up on your radar?

Art: It’s a great story. They were in Minneapolis running a UHF (small, independent) channel. These guys were running that, and they had a big library of movies because they had licensed them. They started doing Joel and the Robots in front of the movies as a lark and then putting them on the air on this UHF station. Now, the thing is that one of the early films that they did was The Godfather, and you cannot license The Godfather to make fun of it. You know what I mean? So, that wasn’t gonna work, they were getting away with it because they were from a very small location.

We at Comedy Channel (Central) were sitting around early on saying “you know, we need a show that’s a watch us watch television show.” Because what the guys were doing with MST3K is what every comedy writer does, which is to sit in front of a TV or a movie and make cracks and tear it to pieces.

So, we’re talking about this show, and I don’t remember the timing exactly, but it seemed like in retrospect that we were talking about it on Tuesday and Thursday somebody walks in with the mail, and its a tape from the Minneapolis guys saying, “Do you have any interest in us doing this for you?” Of course, the short answer was “Well, that was a gift from God, wasn’t it?”

So, naturally, we flew out to Minneapolis, did the deal, and talked to the guys about the kind of movies that they were going to do. I was in charge, actually, of finding said movies. In the early early days, we were not licensing movies that they could do, because it would be tough to get a license to do that to a real movie. So what we did is looked at public domain movies, movies where the copyright had lapsed, nobody had any claim on it, if you had the print you could show it. That’s how they got to all those cheesy, crappy movies. Occasionally, we’d license some of the better monster films. So it was a little bit of a mix at the beginning.

As a VP of Programming, you’ve gotten and given a fair share of pitches. Do you have any particular tips on what makes a good comedy pitch?

Art: Well, I’m reaching back into the archives, aren’t I? I think a good comedy pitch is going to make someone laugh. These days, in order to do any type of pitching, you need tape (footage). I mean, I knew that in the remainder of my television career into the 2000s. Tape was becoming the important part of it, so you’d have to show a piece. If you’re going to show tape, you gotta make sure that it’s funny enough to make everybody laugh, because nobody wants to buy an unfunny comedy.

The other part of it is that, if you have something innovative, it’s certainly worth putting that out there and making sure that part of your pitch is focused on who you’re pitching it to. It’s not about how great the show is or how great the concept is; it’s about what it’ll do for your line-up, what it’ll do for your audience, and what it’ll do for your brand, all of those things.

That said, one of the best pitches I took in my life was Bill Maher pitching Politically Incorrect in a diner. He just said, “I just want to do a talk show where everybody talks, I’m the funny, and we find the line and cross over it lots and lots of times, and I want to call it Politically Incorrect.” That was the whole pitch. We said, “Okay we’ll buy it right now,” which we did.

Theoretically, if you could bring back a series, which one would you choose and why?

Art: I would have to go with Get Smart. The reason is that it was such a brilliant satire on what was going on, I mean that was the days of the Cold War and James Bond. It had a great pedigree because it was Mel Brooks and Buck Henry. Those two guys were among the funniest guys in the world, and they decided to do a series like that.

It came out so great. Don Adams inhabited the role so beautifully. The way it developed was very funny too. #99 was originally in the first episode, but she was not supposed to be a reoccurring character, and she was nothing like the character that she ended up being. She was actually like the character in the movie, capable, knew karate, and saved Max’s life.

The impact that had on the culture at the time, and again I was around then. I mean it showed up on lunch boxes and showed up in executive suite meetings. It was a show that I used to cut my last class in high school to go and watch it when it was in syndication at three o’clock, because it was such a brilliant comedy.

Interested in learning more about the early days of Comedy Central? Art’s memoir, Constant Comedy: How I Started Comedy Central and Lost my Sense of Humor is available on preorder for both physical and digital on Amazon. You can also see what Art has been up to on his Facebook and Instagram pages or his website at artbellwriter.com.

![[REVIEW] ‘PARASOMNIA #1’ IS LIKE A VAGUELY-REMEMBERED DREAM](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/STL187806fsdaf-150x150.jpg)

![[OPINION] THE LAST OF US IS AN ENGAGING STORY, BUT I HATE IT](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TLOU1-150x150.jpg)