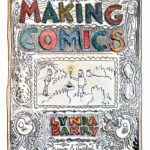

Author: Lynda Barry

Illustrator: Lynda Barry

Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly

Anyone can write or draw. That sort of statement would have been met with howls of derision if it were to come from someone less celebrated than Lynda Barry. It’s hard to underestimate Barry’s contribution to the comic arts, though, because so many of the writers, illustrators, and artists who currently occupy those sections in bookstores around the world credit her with their success. It’s also hard not to be grateful for her commitment to teaching that often surpasses her enthusiasm for publishing new work.

Making Comics opens with examples of student work from Barry’s “Scribble Monster” exercise, presumably taken from one of her many workshops held at universities, community centers, and even prisons over the past decade. It’s a smart way to open what is, essentially, an incredibly well-argued lecture on how we all possess the ability to translate our thoughts into coherent images on paper. “There was a time when drawing and writing were not separated for you,” she opens. “In fact, our ability to write could only come from our willingness and inclination to draw. In the beginning of our writing and reading lives we DREW the letters of our name.’

Readers are then invited to fill in the space below a panel that reads “This Book Belongs To …” It’s clever and, of course, accurate, because that really is how most of us first attempted to draw.

The pages that follow combine Barry’s comments on what she likes with detailed explanations of why she likes them, illustrations that drive her points home, and even perspectives from some of her youngest students such as the two-year-old who describes her drawing as “A fish in the water. And another fish. And this is the moon.” Taken collectively, it makes for an immersive experience not unlike what a discussion at one of her classrooms must feel like. It also serves to illustrate Barry’s powerful premise that anyone and everyone has an approach to art that must be accepted as valid.

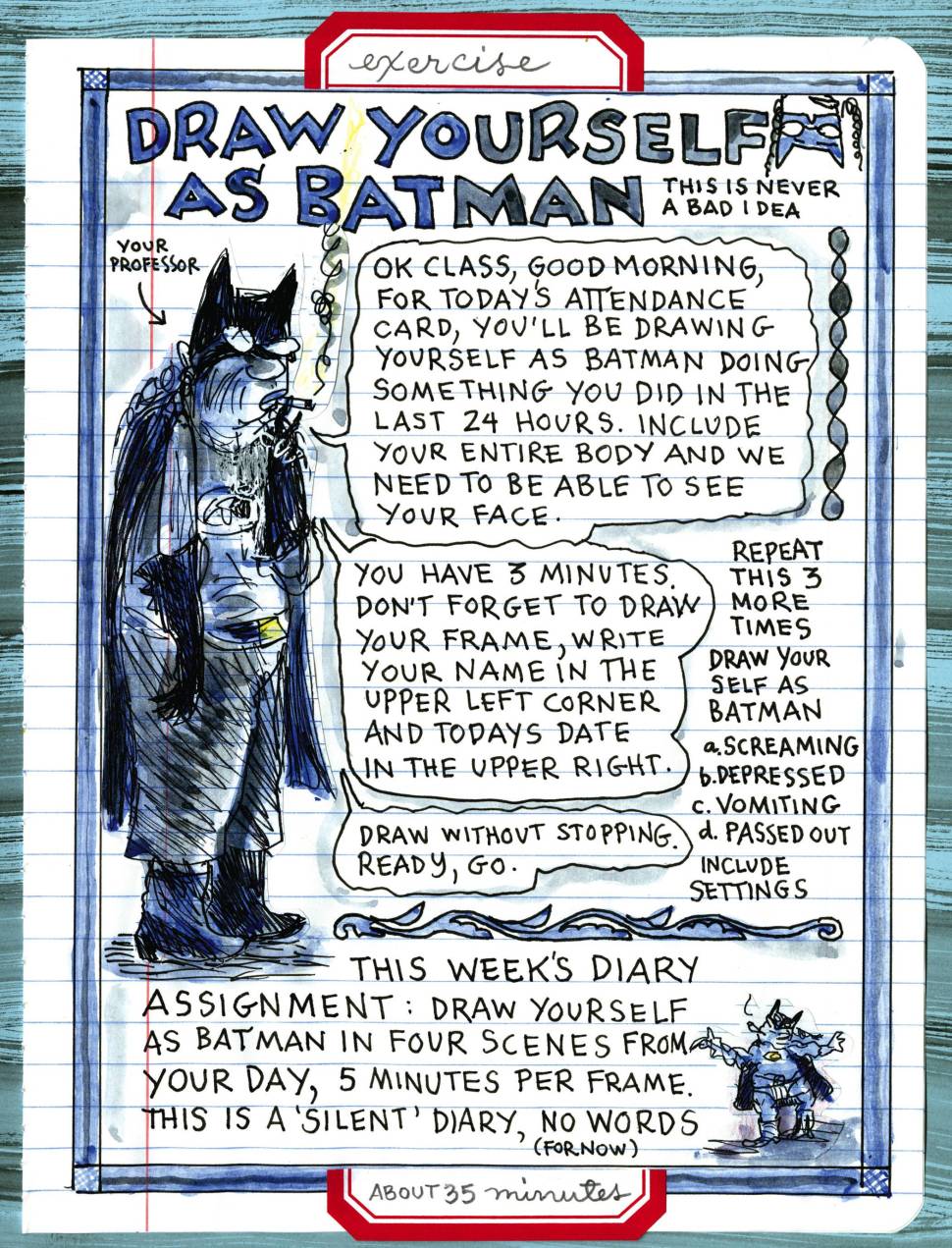

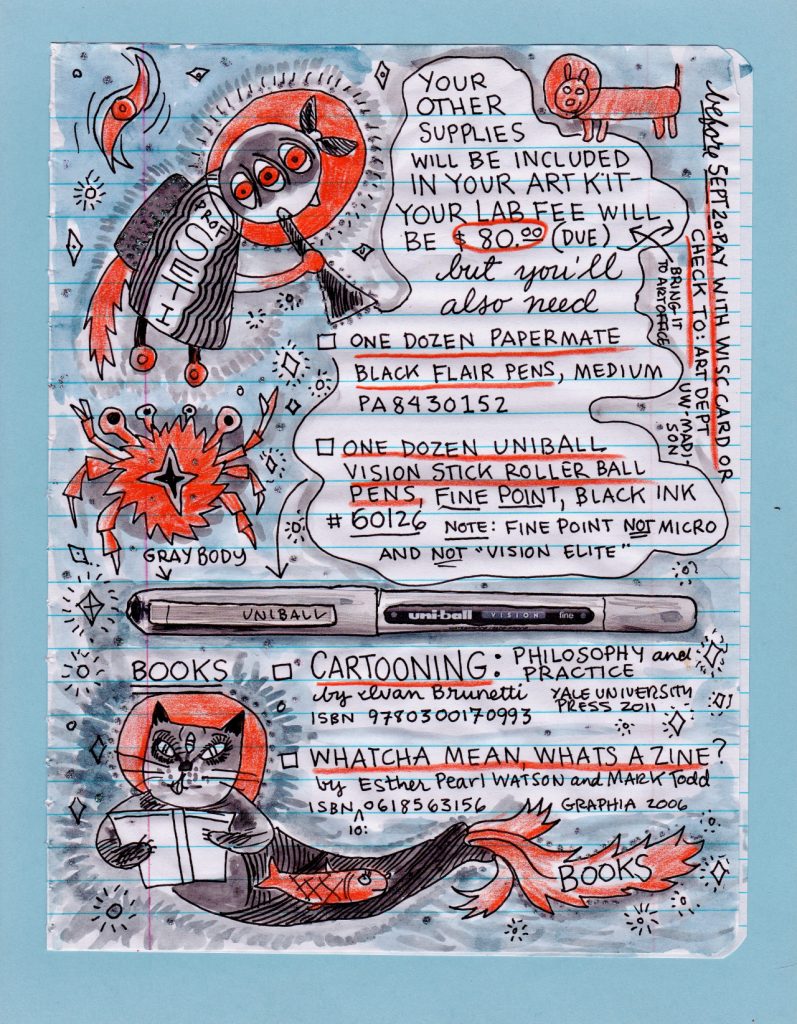

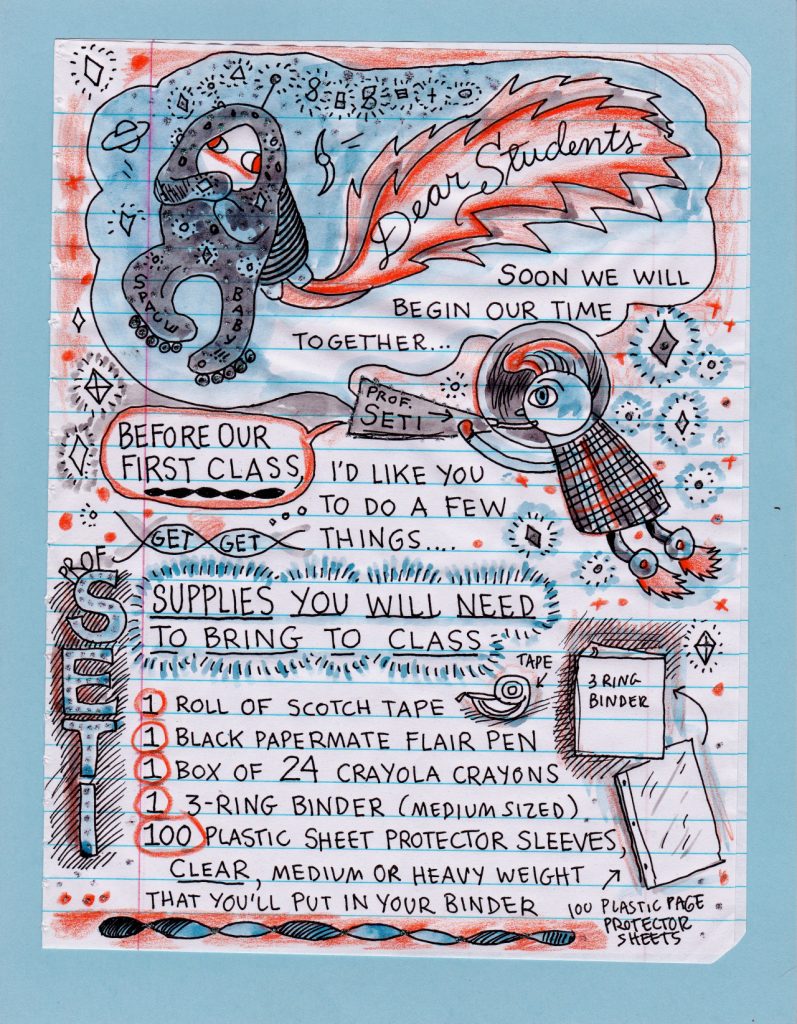

Some of the nicest parts of this book involve the exercises Barry routinely gives her students. This isn’t simply because they are fun (“Draw yourself turning into an animal”) but because they reveal the thought that goes into what they are meant to teach us about ourselves. When Barry recommends keeping a daily comics diary, for instance, she points out that making comics involves the same daily practice that learning any language does, except that part of what we are practicing is a certain way of being in the world and seeing what is around us. It is a remarkably simple yet astute observation.

As the book progresses, the exercises become more complex, evolving into full panels and fully formed characters. There are examples of silent comics, variations on themes, ideas for traditional four-panel comics, and elements of complete stories. There is also a handy “comics kit” with bags for words, pictures, settings, and even camera angles, that almost tempted this reviewer into attempting a comic strip. “Everything good in life came because I drew a picture,” writes our teacher, as her colorful, marvelous lecture draws to a close.

Brain Pickings once referred to Lynda Barry as one of the greatest visual artists of our time. This book is just one in a long list that shows how lucky we are to have her.

![[PREVIEW] ALEX SUMMERS IS ALL TIED UP IN ‘HELLIONS #3’](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/1-3-1-e1598150181261-150x150.png)