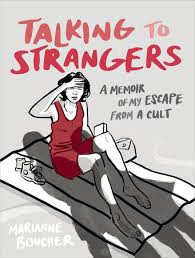

Title: Talking To Strangers

Creator: Marianne Boucher

Publisher: Doubleday Books

There is something undoubtedly titillating about the word cult, thanks in no small part to the endless dramas and documentaries that flood bookstores and streaming services the world over. They are always compelling for readers and viewers, because a part of us is drawn to the idea of these “safe spaces” that are so radically different from the outside world.

What we tend to gloss over, conveniently, is the real damage they inflict upon those who live within them, and it is this crucial fact that makes Marianne Boucher’s memoir valuable.

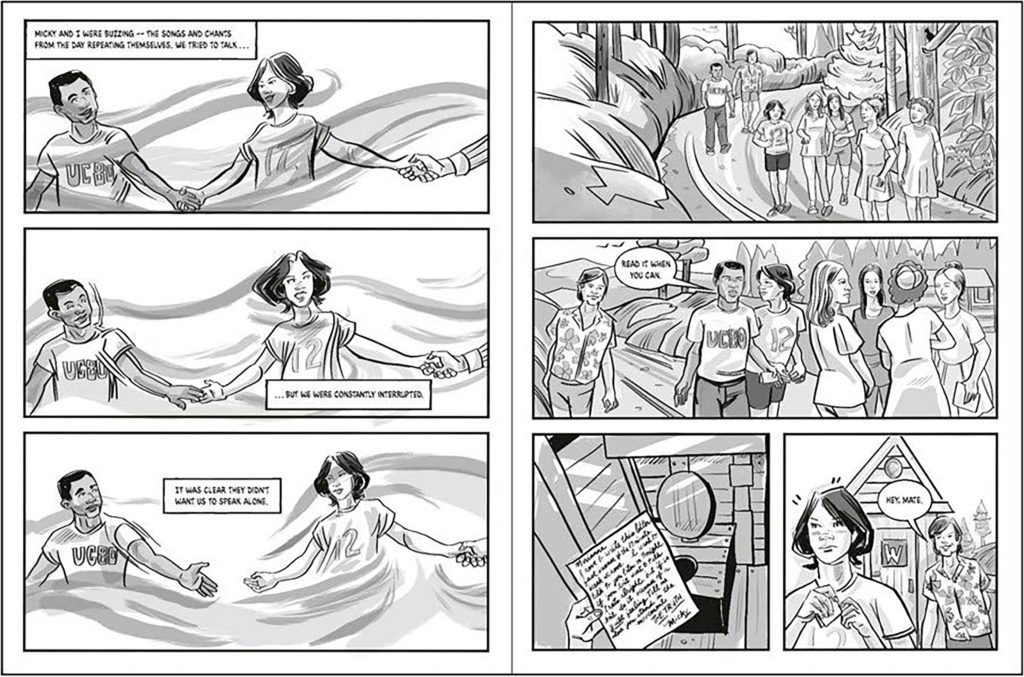

For a Canadian teenager like her in 1980, it’s hard to imagine how a trip to California could have been anything but magical. Boucher was a figure skater at the time and ended up meeting an interesting bunch of people on a beach in that country. They seemed to have an outlook on life that was radically at odds with everything she was taught at home, and offered her a refuge as well as a grand mission that involved saving the world. How could anyone in her position resist?

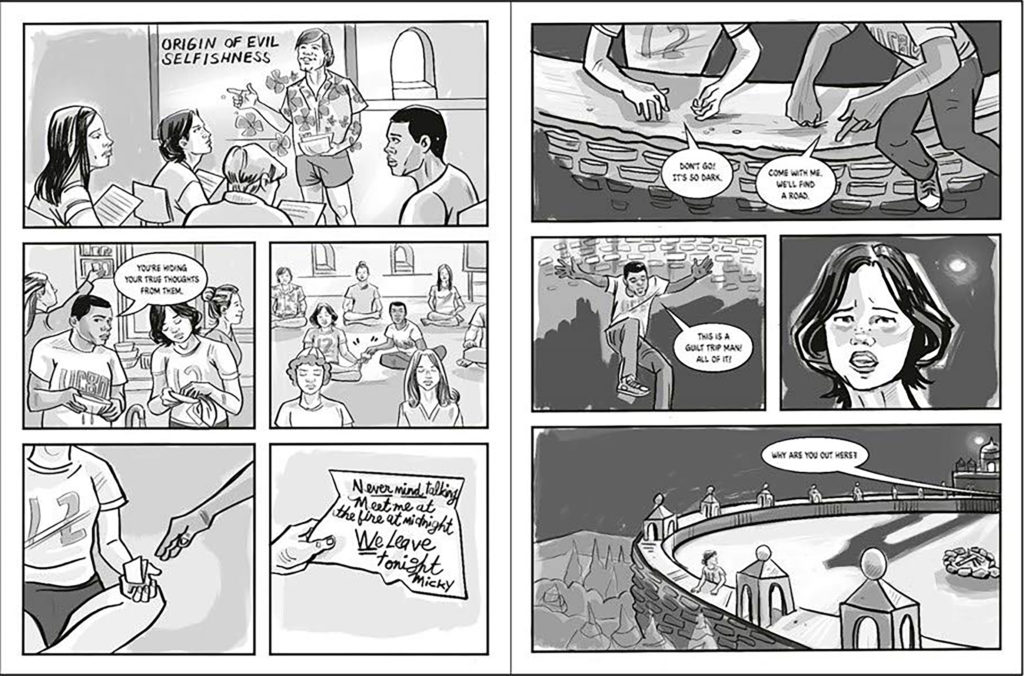

Talking to Strangers is eye-opening not because the writing is particularly powerful or the art ground-breaking, but because it reveals just how mundane a cult can be until the moment one realizes that it is anything but. In terms of style, Boucher uses a rather mannered approach, with her characters well-defined but ultimately hard to distinguish between. In a way, however, this makes sense given how members of a cult often seem to merge into a faceless blur. The postures are also often clichéd, which is presumably done on purpose as well. When Boucher’s mother offers to come and get her, for instance, she holds a hand to her forehead in despair, clutching an Air Canada ticket while her daughter at the other end pulls on a telephone cord in much the same way thousands of teenagers have in coming-of-age indie movies.

For this reviewer, the acknowledgments page was particularly satisfying. Boucher cites the 1976 book Let Our Children Go, by Theodore Roosevelt Patrick, Jr., for further reference. A bit of research revealed that Patrick is known as the “father of deprogramming,” which refers to helping people change their belief systems and getting them to abandon allegiances to groups that most of us would call cults. A lot of these practices are controversial, which is unsurprising, and I wouldn’t have stumbled down that rabbit hole if it weren’t for Boucher.

There aren’t as many memoirs about surviving cults as one would imagine, presumably because those who manage to get out aren’t always excited about reliving a part of their lives that suddenly stops making sense. For Boucher, then, this must have been more than an act of catharsis. For a reader, the brainwashing techniques she chronicles are chilling in their efficiency. There is fear, too, in the form of a spiritual abuser who commands obedience.

What Boucher ultimately manages to do is show that the hardest part isn’t escape, but the aftermath, when one has to rebuild one’s notion of self and regain a sense of identity that has been systematically eroded.

“Welcome to a place where you are valued,” is the promise made by her cult, which sounds like something any professional recruiter would use to entice a new employee. It is this simplicity that also makes it terrifying.