So … Game of Thrones Season 8 was a thing that happened.

Don’t get me wrong, a part of me is relieved the show did come to an end — goodness knows how long they could have kept it going for — but seriously? This is what we get after all this time?

At this point, it’s almost too mainstream to hate on GoT’s final season, so to see another editorial bemoaning how awful and disappointing it was is, I’m sure, like a log being chucked into a forest fire. So, in lieu of nitpicking the last six episodes apart bit by bit, I wanted to take a different approach to discussing the issues in Season 8 of GoT. Let’s talk about why, from a storytelling perspective, the final season of GoT falls short, and some (minimum) ways it could have been fixed.

The Abandonment of Storytelling

I’m a writer by trade and an avid reader, so crafting and understanding story is part of my daily life. Recognizing the masterful storytelling of the first few seasons of GoT was what dragged me into the show’s audience. For me (and I assume many others), it wasn’t about the battles, the scheming, the shocking twists, or anything else — it was how meticulously the story was constructed. How each plot point built upon the others before it. Everything was connected, the characters were well-developed and complex, all actions had consequences, big themes were deeply sewn into the narrative, and every detail mattered.

I don’t think it’s a controversial statement to say that in GoT Season 8 (and maybe Season 7 as well), much of this falls by the wayside. Character arcs are abandoned in favor of subverting expectations; plot threads run out with no resolution; fundamental character traits fall away. In his piece for The Ringer, writer Ben Lindbergh sums up this idea brilliantly:

“Even more so than in Season 7, showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss are playing the part of Daenerys, so fixated on the finish line that they don’t seem to mind how many major story lines are diminished or how many minor story lines get killed in the carnage.”

To sum it up, showrunners David Benioff and D.B Weiss (D&D, as they’re often referred to) seemed to have foregone GoT’s solid story foundations in order to get to the ending they wanted. And seeing as how they literally hid themselves away after the series finale, they know it, too. Granted, their envisioned ending was not without merit (what better way to win the Game of Thrones than to change the rules, after all?) but it petered out in execution. Why, do you ask? Because of storytelling.

Case Study: The Fall of the Night King

If the fact that the Night King was destroyed three episodes into GoT Season 8 fell over you like a bad hangover, you’re not alone. Many viewers, while initially hyped that Arya Stark was the one to kill the Night King, were met with an unsettling question bouncing in their heads: Now what? After all the build-up and anticipation over the last several seasons, the constant warnings that “Winter is Coming,” Jon Snow’s repeated insistence that the White Walkers were the only threat that mattered, they were gone in a blink of an eye.

The greatest existential threat to Westeros and all of the Known World wiped out with the stroke of a Valyrian steel dagger halfway through the final season. We don’t get a thorough enough explanation as to why the White Walkers want to kill Bran and take over Westeros, other than that they’re bad guys. There had been so much teasing and exploration about their origins and what their meaning could be, but there’s never a Horse’s Mouth moment. Arya shanks the Night King, and it’s all over.

Can’t get any more anticlimactic than that.

I’m not going to sit here and debate the merits of how the Night King’s death played out. In fact, Arya being the one to take him out–and perhaps being Azor Ahai (how “darkness” is interpreted in the prophecy can change who the Prince That Was Promised could be)–was totally believable. However, many fans were irritated by how it was executed.

Yes, Melisandre foretells of Arya’s destiny, but as Trope Anatomy put it so well in a recent video essay: foreshadowing is not character development. Dropping hints that a thing could happen is not the same as developing your character to that end. And what makes it so much worse is that, after Arya’s task is complete, she’s essentially dead weight for the remainder of Season 8. The only reason she ends up in King’s Landing is so D&D can give us what seem like never-ending splatter film sequences. She doesn’t grow and doesn’t contribute much of anything after her big moment. The same is essentially true of Bran. He sits there as prey for the Night King, then disappears until basically the last episode.

The way the Battle of Winterfell and the fall of the Night King was set up, it’s clear D&D had a handful of tunnel-vision goals for the final season. Some goals were likely fan service; the rest were probably intended to subvert expectations. These are not inherently bad aims. However, when paired with the shortcuts made in Season 8, these goals inevitably sacrifice narrative, characters, and plot. This is fundamentally bad storytelling.

Flaws In Character (Development)

There are a number of things that went wrong in the storytelling of GoT Season 8. But if I have to boil it down to one major issue, it’s character development. The hard work that brought these compelling and dynamic characters to life was essentially tossed out the window in favor of driving head-on into the necessary plot points and laying out spectacle. Without well-developed characters, you don’t have an engaging story.

Prioritizing Wants Over Needs

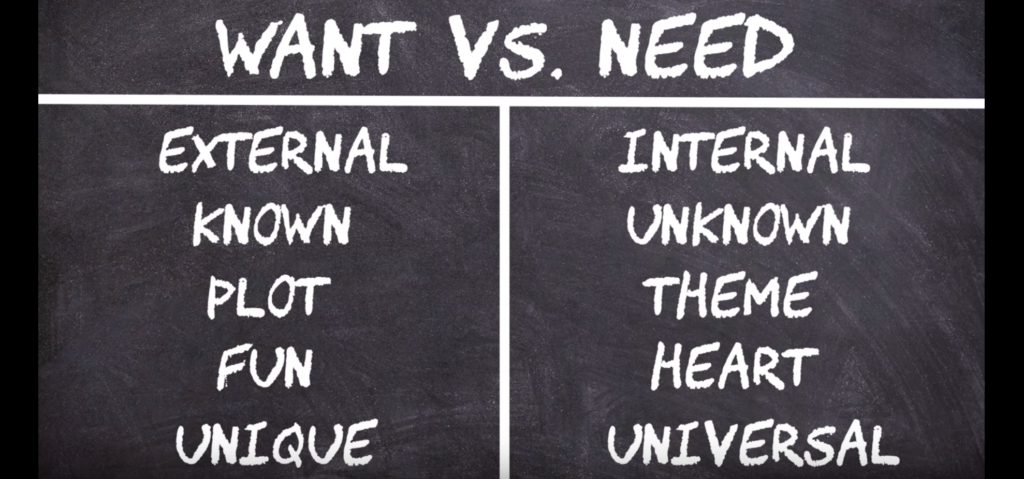

In his video essay on writing strong characters, Daniel Whidden of the YouTube channel Think Story lays out how Wants and Needs are important devices of storytelling. They can help drive well-paced plots while still supporting themes that have emotional stakes. Wants are typically external goals unique to the character, and they are what drive the plot forward. Needs, on the other hand, are universal; they are what the characters need to learn about themselves in order to grow and ultimately fulfill their Wants. Obstacles put in the character’s way can come from either Wants or Needs, but Want-driven obstacles come from the outside world; meanwhile, Need-driven obstacles are usually derived from within the characters themselves.

For a tangible example of this, look at Dany from the start of GoT’s run. With a simple glance, we can clearly identify each of these devices in her character:

- Dany’s Want – To take the Iron Throne and rule the Seven Kingdoms.

- Dany’s Need – To be accepted by others.

Throughout GoT, Dany works to fulfill her Want by building support, obtaining an army, and raising her dragons. Along the way, she also attempts to fulfill her big Need through external actions. Her campaign through Slaver’s Bay won her support from the people; likewise, her burning of the khals and emergence from the flames-inspired fear and allegiance from the Dothraki hordes.

Dany’s actions do earn her some acceptance, but she struggles to achieve the same result when returning to Westeros. The Northerners don’t trust her, and Jon–her strongest relationship besides Missandei and Tyrion–is slipping away. Grappling with the truth of their familial relationship, Jon appears less willing to accept her love and favor. Meanwhile, he continues to garner support and admiration from many more Westerosi than she. Her outward shows of power and benevolence are less valuable now that she has left Essos.

In Season 8 of GoT, it’s clear Dany’s Wants were prioritized over her Needs. By the time the bells are rung, she’s abandoned her internal drives in favor of revenge. As a result, what D&D did by making her the Mad Queen and burning King’s Landing to the ground–killing thousands of innocent people in the process–doesn’t ring true. Her forces have been loyal, her power has been seen, and the citizenry has abandoned Cersei. Everyone is ready for Dany to take the Throne.

So why have Dany become the Mad Queen and destroy everyone in King’s Landing? Because D&D were intent on having the gory spectacle and needed to push Dany into delivering it. Yes, this ending was hinted at before, but if I may remind you: foreshadowing is not character development. Dany’s descent into madness could still have occurred occur while still addressing her Needs. Yet the showrunners appeared intent on subverting expectations, and as a result, pushed all her inward obstacles aside to make it happen.

Disrupting the Hero’s Journey

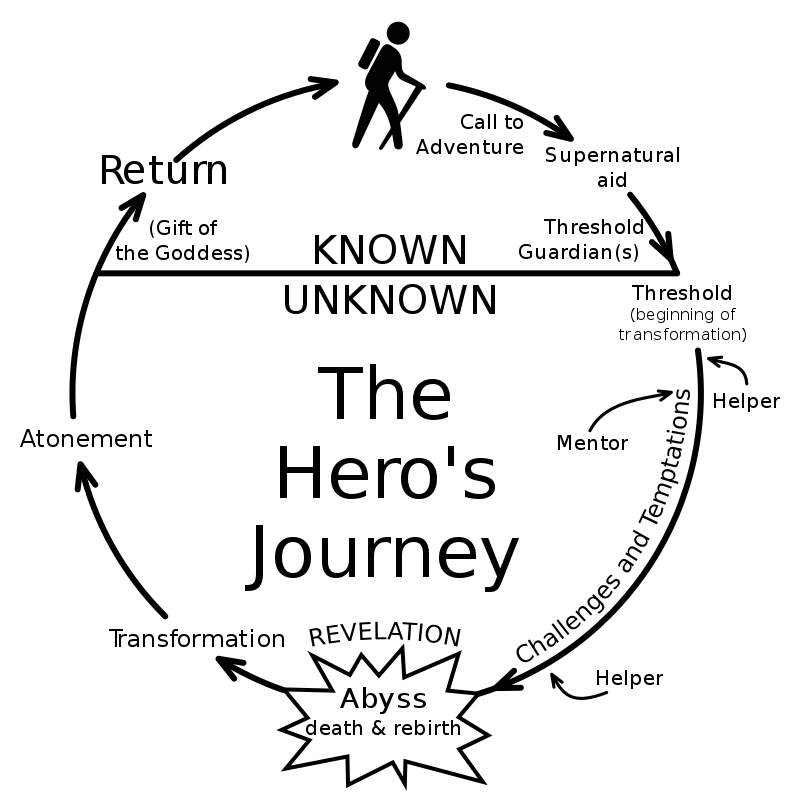

By doing things like prioritizing characters’ Wants over their Needs, D&D committed a fundamental error of storytelling–they disrupted the Hero’s Journey. As a result, motivations are upended, character traits wax and wane, and ultimately leading to a number of unsatisfying conclusions at the end of GoT.

The Hero’s Journey is a narrative structure seen in many stories told throughout human history. It’s essentially a storytelling template for the development of character, plot, and narrative. While the Hero’s Journey isn’t an absolute storytelling guideline, it can be informative. Starting in the known world with the “Call to Adventure,” the Hero’s Journey descends into the unknown. While in the unknown, the character transforms before returning the the familiar fundamentally changed.

The Hero’s Journey works well in GoT because it becomes entwined with the consistent action-consequence structure and level of detail built into the show. However, in the last few seasons, it’s slowly been chipped away at by D&D. Bran is a great example of this in action. His journey has transformed him from a crippled child to a powerful Three-Eyed Raven. But what for?

In Season 8, nothing Bran does advances him as a character anymore, nor does it do anything to the plot. Bran is just sort of … there. Bran becoming the Raven can be argued as necessary to get the White Walkers to Winterfell, but that’s all external. True, he doesn’t outright disclose a disinterest in being a king. But it’s heavily implied. Tyrion, in fact, repeats the implication in the final episode of Season 8. Yet Bran responds to Tyrion’s inquiry about becoming king at the council meeting by replying: “Why do you think I came all this way?”

That doesn’t make sense from the perspective of Bran’s journey at all. Very few moments point to this twist, and nothing Bran does that suggests he knows it’s going to happen either. It just happens. It seems like someone decided “this should happen,” then wrote the necessary plot steps to make it occur. And it doesn’t seem like there was any concern for it feeling natural or genuine, either.

Jaime Lannister: The Ultimate Example of Bad Storytelling in Season 8

This is a hot take: by the final season of GoT, Jaime had probably the most compelling storyline left to tell. But again, D&D seem to have abandoned his arc. The result is wildly disappointing.

When GoT began, Jaime was a selfish, violent man without honor, only loyal to his family. In fact, his own belief that his fidelity to Cersei was the last honorable oath he had left. His sword and his sister were the Kingslayer’s only reasons for living. Through the course of the show, he loses both. He’s forced to rediscover who he is through an unlikely mentor–Brienne of Tarth.

Jaime wants to stay loyal to Cersei and serve her. He maintains a modicum of that loyalty even as he joins the armies at Winterfell in Season 8; he knows the danger of the White Walkers would result in the demise of his sister and their unborn child. Jaime might harbor resentment and anger against Cersei, but his fealty to his Queen still triumphs.

Jaime’s primary Need through the majority of GoT is regaining the higher honor that comes with knighthood. In part, that’s why his knighting of Brienne is so significant. He’s grown to respect the ideals of knighthood, and they guide him to do the just thing. After the Battle of Winterfell, however, he still needs to take one more step.

To restore his honor, Jaime has to do one thing that’s been holding him back: break his last oath. This happens when he and Brienne sleep together. He can now return to King’s Landing as a true knight. At this point, everyone in the audience knows one thing is inevitable–upon his return to King’s Landing, he must kill Cersei.

Instead, Jaime … dies in a cavern, holding her?

I get that subverting expectations is GoT’s thing, but the show never used to forsake its characters in the process. The show established each subversion thoroughly, ensuring they were impactful and meaningful to the larger story. Few anticipated the Red Wedding, but it at least made sense given the characters’ actions. Jaime dies with Cersei just to fulfill a prophecy told earlier in the show and … make Tyrion mad at Dany?

Why Dig So Deep into GoT’s Storytelling Flaws?

If you’ve read this far, you might still be thinking I’m a whiny fanboy. I accept that wholeheartedly; I’m not going to sit here and pretend like I didn’t want GoT to be something more it was in the end; that it didn’t match up with what I’d imagined since day one. I also recognize that I–and many other fans–can’t do anything to change the ending.

In certain types of mental health therapy, there’s this concept of radical acceptance. Essentially, you “accept life on life’s terms” and stop resisting things you can’t change. Such is the case with GoT; none of us can go back and fix what happened with a magic wand. Rather than continuing to harp on it, it’s more productive to just move on. What we got is what we got, and while that’s disappointing, it’s just reality.

I think it’s important, however, to leverage the distance gained with radical acceptance over any piece of media. You can use it to discuss how major story flaws came into being. Learning from failures and mistakes–whether others’ or our own–helps us all grow as both consumers and creators. A writing professor once told me you could learn more from a bad book than a good one, and I believe that to be true. Such is the case with GoT; objectively seeing what went wrong helps us all refine our tastes and our approaches to consuming and creating media. An ability to see what happened in the past–not unlike Bran’s–helps us to improve the future.

![[REVIEW] ‘CLOAKED #1’ IS YET ANOTHER RE-IMAGINED VERSION OF A CLASSIC CHARACTER](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/unnamed2-150x150.jpg)

![[REVIEW] I CAN SELL YOU A BODY #2](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ICSYAB-2-150x150.jpg)

![[REVIEW] HELM GREYCASTLE #1](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Helm-Greycastle-1-alt-cover-150x150.jpg)