I love people who can fix things. Not other people, and certainly not me – I don’t believe in being fixed. Small things. A cake not rising properly, a sock in need of darning, a stubborn television set. As I’ve grown up, I’ve begun to take joy in learning how to do these things for myself. Rescuing a houseplant from near death can inspire pride like nothing else; a couple of weeks ago I helped save a roux for a group meal. Fixing things has become, over the past few years, a way my friends and I show care.

Here’s another thing I love: Fullmetal Alchemist. Hiromu Arakawa’s manga was first serialised in 2001, adapted for anime for the first time in 2003 and remains, fourteen years and a far more faithfully adapted anime on, one of my most treasured stories.

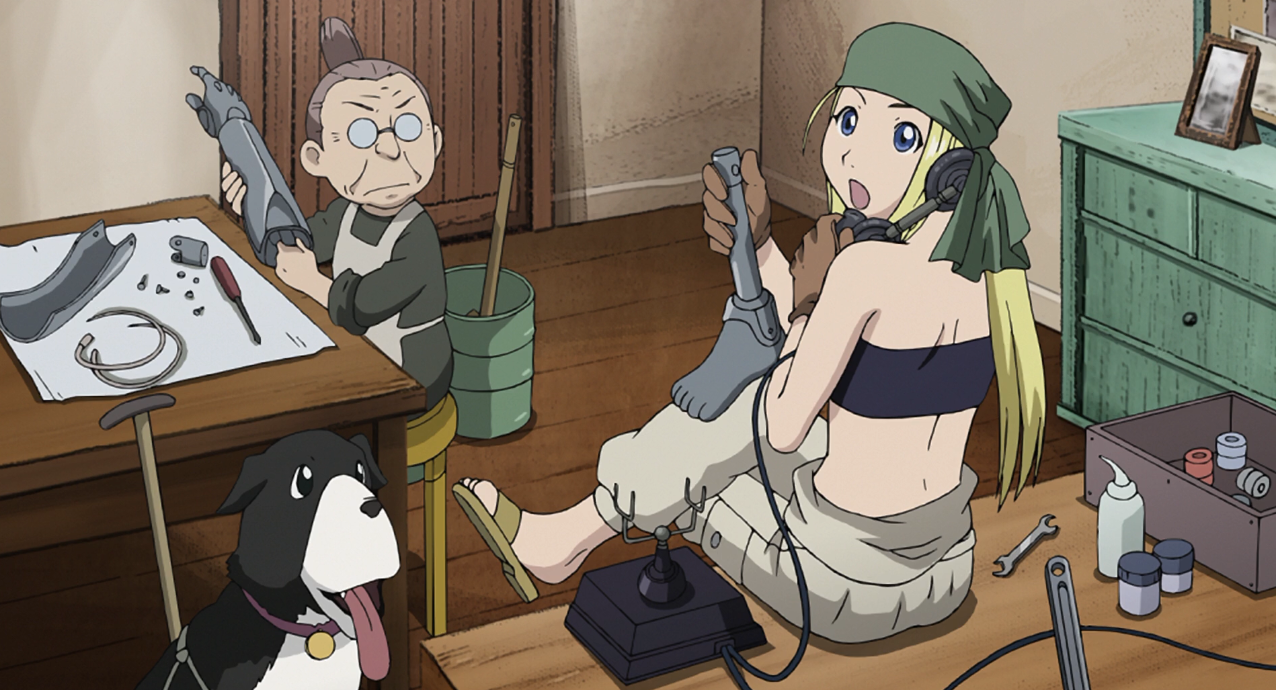

It was in Arakawa’s parallel world of alchemy and automail that I fell in love with Winry Rockbell. She, in the midst of a beautiful winding narrative of trauma and loss, was a consistent source of gain, or regaining. Winry Rockbell fixed things; she fixed arms and smiles and in my stilted, nine year-old way, I loved her.

I say I don’t believe in being fixed as though opinions themselves can be fixed points in a world of endless rapidities. It’s not that I always felt this way, and perhaps what drew me to women who seemed so certain in their craft, so able, was a sense that I myself was a confused object in need of concrete certainty. Bisexuality is – when you’re ‘just starting out’ in the self-exploration and self-reckoning required of simply being – a confusing terrain. Everybody’s story is different: the fluctuations in opinion and identity and sexual intention. It is real and true and not the all-too-readily deployed ‘phase,’ but let’s not kid ourselves in claiming it’s easy.

Maybe what I craved in my adolescence wasn’t to be fixed, but to be tinkered with. Something in my chemistry could have been adapted, I would wager, making things easier to deal with. It would have been a relief to have some adjustment made, to have things shift into place, wheels spinning with no resistance. A soundless ease.

As I grew older, grew into myself, I found some certainty in my love of science fiction. In my mid-teens, I found one show which piqued my interest in the possibilities of space narratives beyond my beloved, formulaic Star Wars. I’d just finished watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer for the first time when I came across ‘nine people looking into the blackness of space and seeing nine different things’ and met Firefly’s engineer, Kaylee Frye. My many issues with Joss Whedon aside, Kaylee was a boon to my melancholic, depressive teen years – she fixed my mood as she fixed spaceships, sunnily and fashionably.

As I grew older, grew into myself, I found some certainty in my love of science fiction. In my mid-teens, I found one show which piqued my interest in the possibilities of space narratives beyond my beloved, formulaic Star Wars. I’d just finished watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer for the first time when I came across ‘nine people looking into the blackness of space and seeing nine different things’ and met Firefly’s engineer, Kaylee Frye. My many issues with Joss Whedon aside, Kaylee was a boon to my melancholic, depressive teen years – she fixed my mood as she fixed spaceships, sunnily and fashionably.

Now, in my twenties, I occupy a strange space in academia. I am a literary and cultural studies postgraduate interested in STEM, in the social and ideological world surrounding science and technology, in the gendered divisions of labour in the field. Perhaps it is my preoccupation with binaries which led to my obsession with science fiction and the categorisation of data and experience. Either way, I continue to seek out women in fiction who know what it is to fix things. Not men, and often not themselves, but objects. The Expanse’s Naomi Nagata has recently taken up the mantle.

Fixing is laborious. It takes a certain kind of effort that is all too easily gendered. But in those first few tentative years, where I explored my sexuality with no confidence and no blueprint, I needed the kind of care it takes to fix things. I was a roux to be set right; a sock to be darned.

Women (fictional or otherwise, and often mythologised somewhere in between) who knew themselves and their craft meant something to me, even if they couldn’t directly provide that care. I did not need to be fixed, in that bisexuality was and is not a fault in my machinery, but a guide would have been nice. Instead, these competent women and their wrenches would have to suffice. Even as I know it is the world which needs fixing, I still return to them, taking notes for a time I find something I can fix myself.