Class Warfare? The One Percent in Comics

The return from hiatus of The Black Monday Murders gives us occasion to check in on an increasingly-popular subject in the comic world: the one percent. Comic companies have come under fire of late for their treatment of social issues such as race and gender, but how have they fared in their consideration of income inequality? Jonathan Hickman’s recent effort joins Renato Jones and Green Arrow in hinting that wealth disparity is beginning to garner serious attention in comic books, but that creators have yet to exploit the subject to their full advantage. For now, class conflict is a one-sided affair, limited to warring groups of rich who battle one another for control over the destiny of a declining middle class.

All Hail, the God of Greed

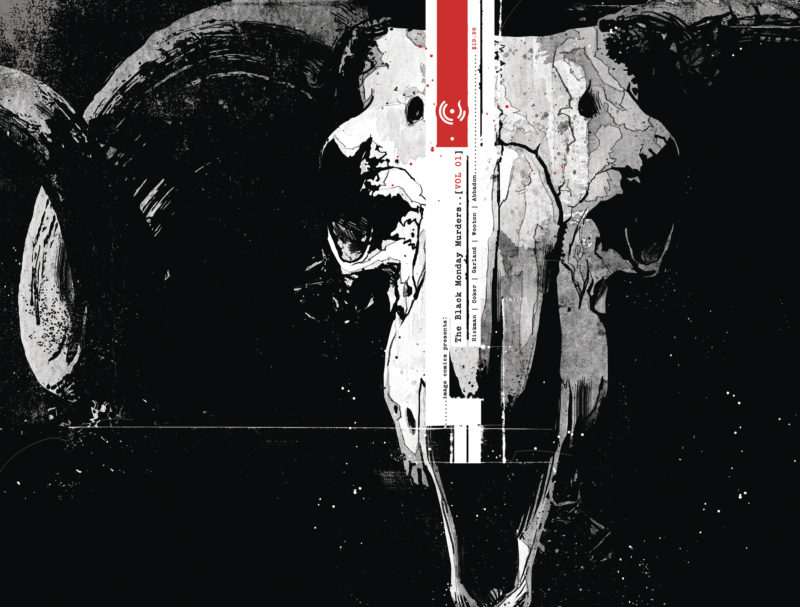

The simplest takeaway from all three comics is that the global economy is rigged in favor of the wealthy. In Black Monday Murders, detective Dumas’ investigation into a ritual murder uncovers a conspiracy of financiers who use magic to manipulate the stock market. The spooky refrain that echoes across both arcs of this Image book, All Hail, God Mammon, is a prayer to the god of greed and a rallying cry for the haves against the have nots. The protagonist of Image’s Renato Jones meanwhile fights this war on behalf of the poor. This vigilante travels the globe, murdering a gallery of thieves and rapists who bear an uncanny resemblance to famous members of the one percent, such as Donald Trump and Steve Jobs.

Rich-on-Rich Violence

But the narrative conflict in both comics centers almost exclusively on the super rich. Hickman’s story has thus far focused on warring factions of rich occultists, led my Ria and Viktor, who seek to dominate the global economy. And, if the last issue is any indication, Detective Dumas has no interest in standing up for the ordinary folk trod upon by this struggle. Neither book makes an effort to treat the working poor as more than ‘suffering background’ against which aristocrats, including Renato Jones, jostle with one another for control. Seasons One and Two of Kaare Kyle Andrews’ comic, treat us to a Bruce Wayne-like billionaire who, with the help of his butler, uses his considerable inheritance to snuff out the worst of his class. Even this anti-hero’s nickname, The Freelancer, obscures the issue of wealth inequality by linking Jones to a generic gig economy that could apply as easily to a computer programmer as an Uber driver.

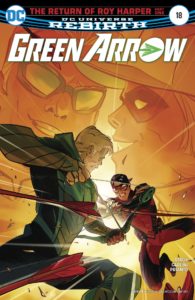

Paradoxically, a former billionaire is the closest these recent comics have come to depicting an authentic working-class struggle for economic justice. By stripping Oliver Queen of Queen Industries, Benjamin Percy has turned DC’s Green Arrow into one of the most progressive mainstream comics in the recent past. Queen’s struggle to escape the machinations of a corrupt police force, his fight against an evil multinational syndicate of CEO’s and financiers known as the Ninth Circle, and his Middle American odyssey pulls the focus away from privileged superheroes and onto the struggles of everyday people.

But not enough to make readers forget that this is still a story about the one percent. Queen is not rich anymore, but he not ordinary either, and the heart of this comic is a moral tale of an advantaged person who makes amends for the privileges afforded to him by his status. The ordinary people of Star City and Seattle are still rendered in the abstract, as anonymous evidence of the suffering that drives Queen to be a better person. Green Arrow is a bit like Renato Jones – both are about the rich learning to police themselves. That is why the Queen’s argument with Lex Luthor about social justice in Green Arrow #28 felt a bit like listening to Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg discuss what it is like to live on minimum wage.

Who Gets to Fight for Economic Justice?

Comic creators hoping to make a point about income inequality lose an opportunity by relegating the rest of us to deep background. Portrayals of ordinary people as victims, not soldiers in their own wars for economic justice, raise issues of agency and representation similar to those applied by comic fans to women and people of color. A working-class (super)hero fighting the class war only complements the meaningful discussion unfolding in comics about witches, vigilantes, and archers who rig our economy.

![[MAY THE 4TH BE WITH YOU] NINE OF THE WEIRDEST THINGS IN STAR WARS LEGENDS](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Untitled-design-150x150.jpg)