There’s something irresistible about the unobtainable. From the unnervingly realistic food in Final Fantasy XV (2016) to the simple dishes made complete with a side of visible pixels in Cooking Mama (2006), food in video games has almost as interesting a history as the history of the games themselves. Used to restore health, as plot devices, or as an added aesthetic touch, food in video games keeps people alive and draws them together just as often as it does in real life. It also has the power to actually stop you from playing a game for an hour or two in order to indulge. I’ve been inspired to try new foods or even make them to the best of my ability myself after something in a game has caught my eye (and my stomach). This, of course, is what any good game should do: inspire you.

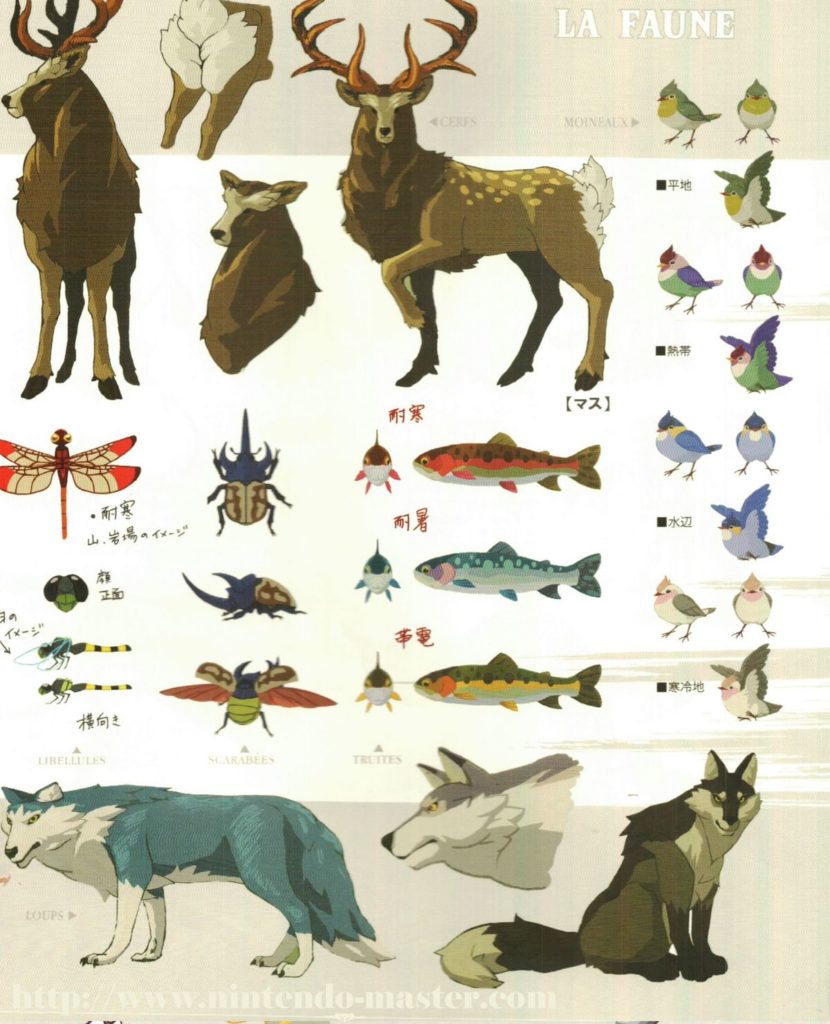

My thoughts on the importance of food in video games were refreshed recently after playing through the majority of Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. In Zelda’s latest, an adventurous and omnivorous Link can hunt, kill, and cook any of the animals that cross his path (aside, of course, from a Hylian’s best friends – horses and dogs). Interestingly, included among the meatier options are wolves, coyotes, and foxes. At first I thought this strange – despite their wild nature, those majestic canids are among some of the world’s most beloved animals. But Link can’t afford to think entirely empathetically, not now, while his world is in ruins. If it has four legs and meat on its bones, unfortunately it’s fair game. To make only herbivorous mammals, birds, and fish available for consumption would be doing the game’s theme of survival a disservice. Harsh, but true – unless of course you choose to play Link as a vegetarian or a vegan, both entirely possible in this game. A Reddit user recently discussed how Breath of the Wild helped them finally take the first step towards vegetarianism, not because of the way the animals were depicted in death, necessarily (as they alchemize rather cartoonishly into perfect cuts of meat) – but because the very act of hunting in the game had them stop and question why it was they ate animals in the first place.

In M. F. K Fisher’s cookbook (of the same name as this article’s title), cooking a wolf means working with what you have. Times of shortage, desperation, difficulty, or times without much time, mean you must make due (and creatively utilize) whatever was available was something to aspire to. In Breath of the Wild, Link can instantly transform a lean cut of wolfsteak into a rice dish imitating what we might know as beef donburi, or even add some spice and more rice to create a delectable curry. Though the recipes are not endless, combinations of ingredients are almost so, and experimenting by adding to base recipes can really liven up what might be an otherwise repetitive few minutes of play.

For me, this way of restoring Link’s health was much more meaningful than cutting down grass or smashing pots like in previous Zelda games. It created more of a fiction, allowed me to immerse myself in the environment, and had me literally put time and care into Link’s well-being. Should he eat a spicy pepper-based dish or a whole fruitcake before venturing into a snow-covered area? The answer is obvious, but the act of gathering ingredients, putting them together, and allowing Link to enjoy his hard-earned meal before continuing his trek was enjoyable from start to finish.

What makes the inclusion of food more than just a new mechanic in Zelda’s gameplay is the way it is also written into the fiction of the world itself. Several side-quests involve the gathering of ingredients and even the preparation of dishes by Link himself, give or take a few helping hands. Mild spoiler alert – one side-quest has you gather ingredients to help a family make dinner. What you end up getting in return for your foraging is an invitation to join them for said dinner, along with a generous portion of what was made – seafood paella. I won’t lie and say I didn’t get emotional at such an unexpected gesture.

In Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule, small villages are swamped by vast wilderness, and fellow Hylians are few and far between. To venture through the unknown and arrive as a stranger, only to be invited to dinner by a family who are, in the game’s fiction, just as desperate to survive as anyone else, was touching beyond belief. The side-quest doesn’t really get you anything spectacular, other than that free food and a new recipe, but that’s reward enough in itself. In fact, so meaningful was this brief diversion for me that I would have been happy with nothing at all – only the implication, as the screen faded to black, that Link had shared a good meal with some good people.

Food in video games should, ideally, be used in this way. Beyond being practical during gameplay and entertaining to create, it’s also deeply meaningful and a part of character development. Another relevant spoiler – in Zelda’s diary, she reveals that she finally got Link to open up to her over – you guessed it – food. It seems Link has always been ravenous and interested in the culinary arts, and his characteristic silence was finally broken when Zelda brought up food. Although the details of their conversation aren’t given, if you’ve seen the way Link looks so satisfied after downing a mushroom skewer or hearty potpie, it won’t be too difficult to fill in the blanks. Food is as important to the people in Hyrule as it is to us, and shouldn’t only be seen as a fun and flexible new game mechanic, but appreciated as an integral part of Zelda’s lore.