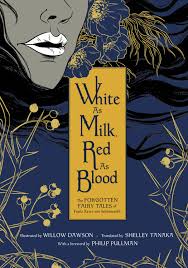

Title: White As Milk, Red As Blood

Title: White As Milk, Red As Blood

Writers: Franz Xaver von Schönwerth, Shelley Tanaka

Artist: Willow Dawson

Publisher: Knopf Canada

Fairy tales are often mistakenly believed to be meant for the amusement of children. The Brothers Grimm can be blamed for this, although, to be fair, a lot of their collected stories were adapted to modern sensibilities in ways they couldn’t possibly have foretold. How could they have assumed, for instance, that the Third Reich would use them to foster nationalism? Or that Walt Disney would sanitize the brutality of much of their work to build an empire upon?

This is what makes the archives of civil servant Franz Xaver von Schönwerth important. Discovered exactly a decade ago in Germany, they were everything the Grimm collections were not — unpolished, darker, often shocking, always based on oral traditions. Schönwerth and the Grimm brothers were contemporaries, and presumably they had access to the same Bavarian storytellers, which is what makes the former’s collections seem so surprising when juxtaposed against the more popular editions promoted by the latter. It may also explain why the Grimm tales went on to compete in sales with the Bible, while Schönwerth’s raw compilation languished in obscurity.

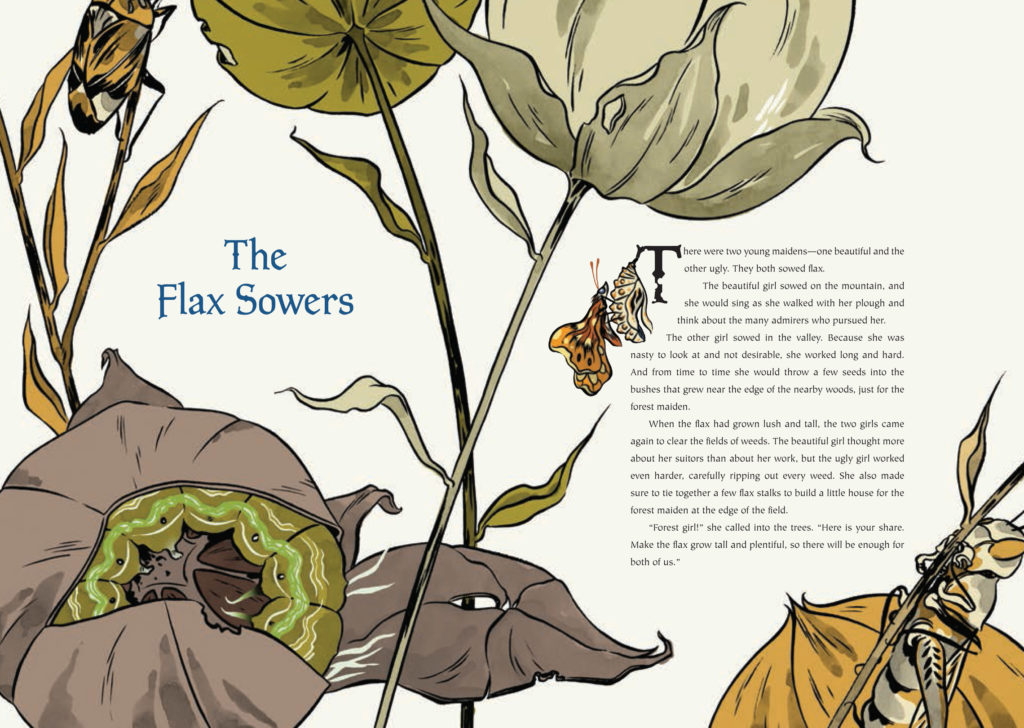

Luckily for us, this illustrated (by Willow Dawson), translated (by Shelley Tanaka) edition brings those forgotten tales kicking and screaming into a world that has forgotten what fairy tales once were. They are twisted, racy, foreboding, and intense narratives of witches and shape-shifters, giants and even a serial killer, all of which ought to be kept from the reach of children.

This is a win-win for lovers of storytelling as well as graphic novels, given that the tales are engrossing and extremely entertaining, and that the illustrations follow a woodcut-style that is both apt as well as striking. It makes for a collection that more than earns pride of place alongside any respected study of mythology or classical literature. Much of its power — as Philip Pullman explains more succinctly in his Foreword — stems from the odd sense of comfort we have come to expect from fairy tales, combined with the strange sensation of being introduced to something completely new. In taking what appears to be familiar and making it seem odd, von Schönwerth compels us to look at the world from a fresh perspective.

Apparently, there were around 500 stories discovered in the archive, along with other things recorded by Schönwerth — including nursery rhymes, children’s songs, proverbs of the time, as well as children’s games. Some were published by von Schönwerth in his lifetime, but most were not, which is why they emerge almost like snapshots of a forgotten era, chronicling the morals by which Bavarians lived as well as the dialects, clothing, and customs that governed their everyday lives.

This is the kind of mix one can dip into at random, with some stories coming across as fully formed, and others seeming almost abrupt. There is none of the loveliness and charm one expects while reading what we think a fairy tale should be like, but that is precisely why they matter.

Interestingly, Jacob, the elder of the Brothers Grimm, believed that Schönwerth was the only person capable of continuing the brothers’ work. If that’s not a decent celebrity endorsement, what is?