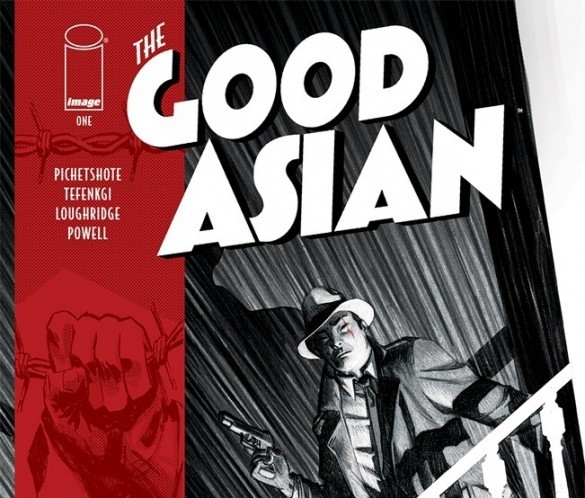

Last year, the Washington Post published an opinion article written by economist and politician Andrew Yang. Amidst the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes, Yang argued that Asian Americans should do everything within their power to “show our American-ness” as a form of goodwill. And while well-intentioned, Yang’s musings were criticized as a form of respectability politics. This is the idea that a marginalized group must earn acceptance by proving how assimilated they are by presenting good, respectable behavior. But as Yang himself proves, marginalized groups are not immune to the endorsement of respectability politics. This conflict is the central though line that drives Detective Edison Hark in The Good Asian #1 by writer Pornsak Pichetshote and artist Alexandre Tefenkgi.

Last year, the Washington Post published an opinion article written by economist and politician Andrew Yang. Amidst the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes, Yang argued that Asian Americans should do everything within their power to “show our American-ness” as a form of goodwill. And while well-intentioned, Yang’s musings were criticized as a form of respectability politics. This is the idea that a marginalized group must earn acceptance by proving how assimilated they are by presenting good, respectable behavior. But as Yang himself proves, marginalized groups are not immune to the endorsement of respectability politics. This conflict is the central though line that drives Detective Edison Hark in The Good Asian #1 by writer Pornsak Pichetshote and artist Alexandre Tefenkgi.

Set in 1936 Chinatown, The Good Asian follows Edison Hark, mainland America’s first Chinese American detective. He is tasked with finding Ivy Chen, a maid and secret lover of Edison’s surrogate father, millionaire Mason Carroway. But what starts as a simple missing persons case quickly escalates into something more dire.

Like a lot of crime thrillers, The Good Asian hits many of the same beats. There’s bad cops and good cops (or rather, fewer bad cops), sex appeal, a mystery, and violence. But at its heart, this is an unabashedly Asian American story. Instead of a drinking problem or marriage issues typical of the standard, overworked detective, Edison Hark deals with issues of identity. In fact, it becomes clear that “Edison Hark” is a mask worn by our protagonist to help him navigate the American justice system, a system that puts him at odds with his own people while simultaneously keeping him at arm’s length. To some, he is a good Asian; to others, he’s a sellout. It’s a compelling perspective that quietly subverts the trope of a detective that simply can’t do his job right because of a restrictive justice system.

I wasn’t entirely sold on the art in The Good Asian: it looks a bit too soft and round for a gritty crime thriller. But by the end, that notion is completely thrown out the window. The year is 1936 in Chinatown, San Francisco. It’s a time and a place where its citizens are treated as inferior and the fear of deportation could happen at any moment. It’s a stressful time period, and Tefengki’s art does a deft job of capturing it among the characters’ facial expressions. Scenes of violence are also paced well for dramatic tension, and it feels like the worst possible scenario is going to happen during these moments.

Contributing to the art is Lee Loughridge’s colors, which also work surprisingly well. Different sections of the book have their own color scheme, and it makes the art pop and remain engaging throughout. There’s even a shocking use of hot pink that is highly reminiscent of neo-noir films. An interesting thing is also done with the lettering by Jeff Powell, in which dialogue spoken in Cantonese is indicated by a square word balloon and anything spoken in English uses a round one. I found myself confusing the square word balloons with the standard box narrations, but it’s a neat way to create less copy, and it’s something that I quickly embraced.

Pichetshote and Tefenkgi have crafted a smart and tightly-paced Chinatown noir that takes on the model minority theory head-on. In The Good Asian, actual working class Asian Americans are featured, and it isn’t exactly glamorous. Tefenkgi’s pencils are a surprising fit for this gritty 1930s noir tale, and Loughridge’s use of colors makes each section of the story pop. The Good Asian is an evocative title, and, thankfully, it delivers. And like any good mystery, it keeps you on your toes and eagerly flipping pages. Be sure to pick up a copy of The Good Asian #1 wherever you get your comicbooks.