Authors: Robert L. Marshall, Traute M. Marshall

Authors: Robert L. Marshall, Traute M. Marshall

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Year Published: 2016

Pages: 280

It has been a little over three centuries since Johann Sebastian Bach walked the Earth, and over two centuries since the rest of us recognized that there was something extraordinary about the music he created. 335 years after he was born, his influence only continues to grow, affecting everything from classical music and art to mathematics and the sciences. Millions of words have been written to try and explain why that is, but Exploring the World of J. S. Bach: A Traveler’s Guide is possibly the first book that tries to show how the places he lived in played a significant role in his development.

Robert L. Marshall is a respected professor of music, while Traute M. Marshall is a writer and translator. The two scholars are more than equipped to talk about the music of Bach, but what they have chosen to publish instead is a history lesson unlike any other. It is a book that is delightful in its complete lack of pretension, coupled with unbridled enthusiasm for its subject.

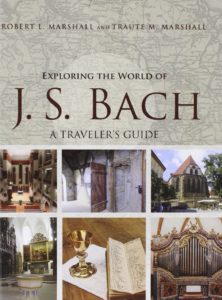

The premise is simple enough: a travelogue that covers over 50 towns in which Bach visited, resided, or worked. In 280 pages, the Marshalls manage to do more than bring the Baroque period to life. They use maps, color photographs, and nearly 100 historical illustrations to create a work that will appeal not just to Bach enthusiasts but to anyone mildly obsessed with Instagram. It is equal parts social history, travelogue, memoir, and biography, making for a surprisingly engaging look at one of the most iconic musicians of all time. What this reviewer liked best was the fact that so many of the photographs had been taken by the writers themselves.

At its heart lies a well-documented trek made by Bach in 1705, when he was 20. He walked approximately 250 miles, from Arnstadt in Thuringia to Lübeck near the Baltic coast, to study music under one of Germany’s most famous organists, Dietrich Buxtehude. The sheer passion for what he eventually spent his life doing comes through when one considers the enormity of that exercise at a time when travel was not the seamless Google-enabled activity it is today.

By shadowing that young man three centuries later, the Marshalls re-introduce a piece of lesser-known music history. They also reveal stunning locales, often far removed from tourist trails, almost all begging to be rediscovered. From the Harz mountains to Brocken summit, the Old Salt Road from Lüneburg to the legendary Marienkirche church that Buxtehude played in, there are a thousand points of interest, irrespective of whether one loves the music or not. There is even a photograph of the gold chalice that Bach and his wife took communion from, supposedly still in use at St. Agnes’s Church in the city of Köthen. These images all throw into sharp relief the sheer size of the shadow Bach cast, given his humble origins.

There are all kinds of scholarly studies on Bach, classical music, the Baroque period, and even the evolution of the German nation. What there isn’t is a way of making sense of these weighty issues for a generation weaned on instant gratification and short attention spans. If we have more books like Exploring the World of J. S. Bach, tomorrow’s history lessons may be a lot more interesting than the ones so many of us were forced to sit through.

![[REVIEW] I MADE THE CAULIFLOWER CASSEROLE FROM ‘HAHA #5’](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Haha5-150x150.jpg)