Author: Marcel Proust

Adapter: Stéphane Heuet

Artists: Stanislas Brézet, Stéphane Heuet

Translator: Laura Marris

Publisher: Penguin Random House / Liveright

It takes a particularly brave writer or illustrator to try to distill the wit and wisdom of Marcel Proust’s overwhelming novel À La Recherche du Temps Perdu into a graphic adaptation. The risks are innumerable, from a potential loss of nuance to the highlighting of sections that may lend themselves to a drawing but fail to carry the emotional heft that other written sections possess. Stéphane Heuet obviously knows what he is doing, though, which is why this second volume of a work that began in 1998 now exists.

The French hated the graphic novel when it first appeared, which makes perfect sense given how they also protested when a fast food company dared open a branch on their shores. They appear to have made peace with the former, much as they clearly have with the latter, and this has a lot to do with Heuet’s undeniable familiarity with the source material.

Proust wrote his seven-volume work between 1871 and 1922, and it is a dense chronicle that begins with the narrator’s childhood and culminates in adulthood, documenting not only France of the aristocrats but fundamental questions about life, time, and meaning along the way.

The first volume, Swann’s Way, focused on the narrator’s interactions with his family friend Charles Swann and an infatuation with his daughter Gilberte. There were other characters and events — some trivial, others that led to repercussions and prompted more powerful recollections as the narrator grew older. The second volume is titled In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, which is a pretty apt description of how tricky adolescence can be for anyone, especially a young man struggling to interact with women his age.

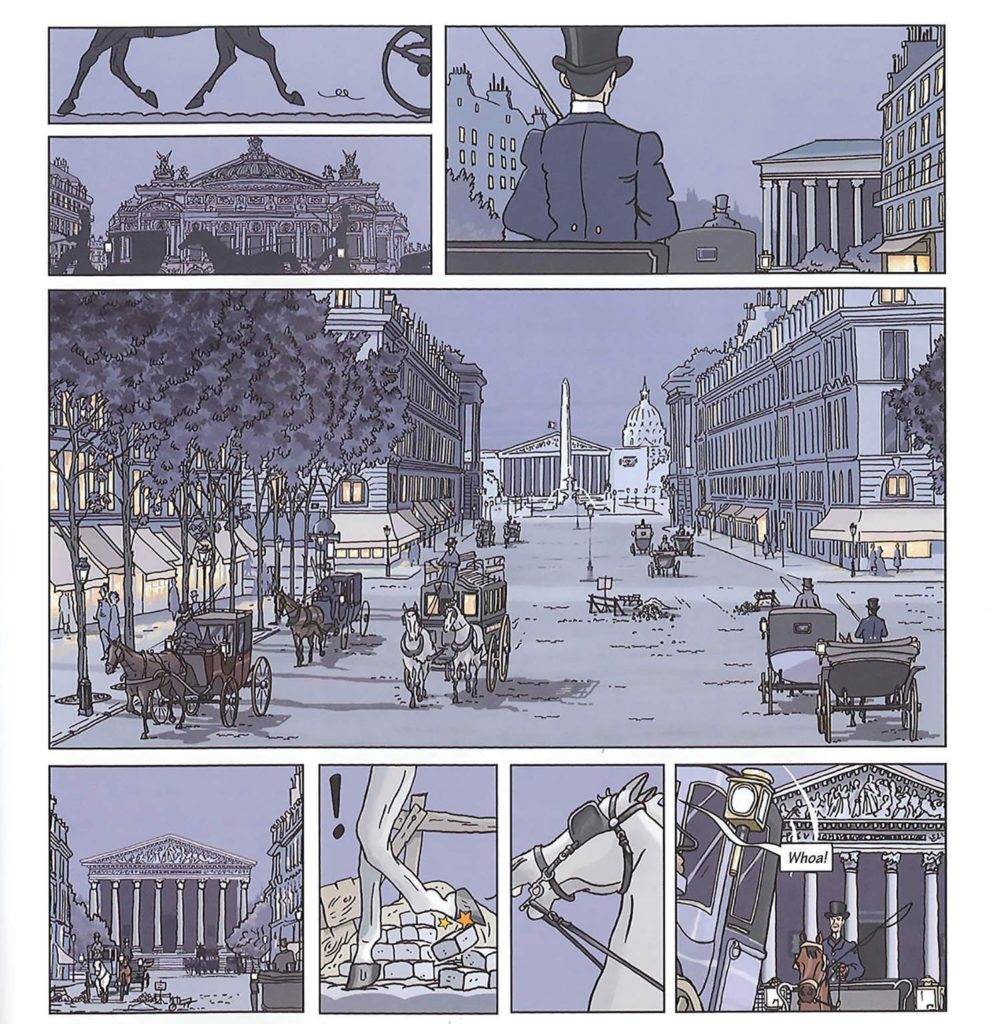

There is also a change of setting, from the fictional Combray to Balbec, a seaside town modeled on the real-life Cabourg in Normandy. The nature of experiences changes drastically here, as the narrator is exposed to darker aspects of society such as the importance of class. There is an exploration of sexuality as well, as he slowly gets over Gilberte Swann and begins to gravitate towards Albertine, a woman who will grow to occupy much of his attention in forthcoming volumes.

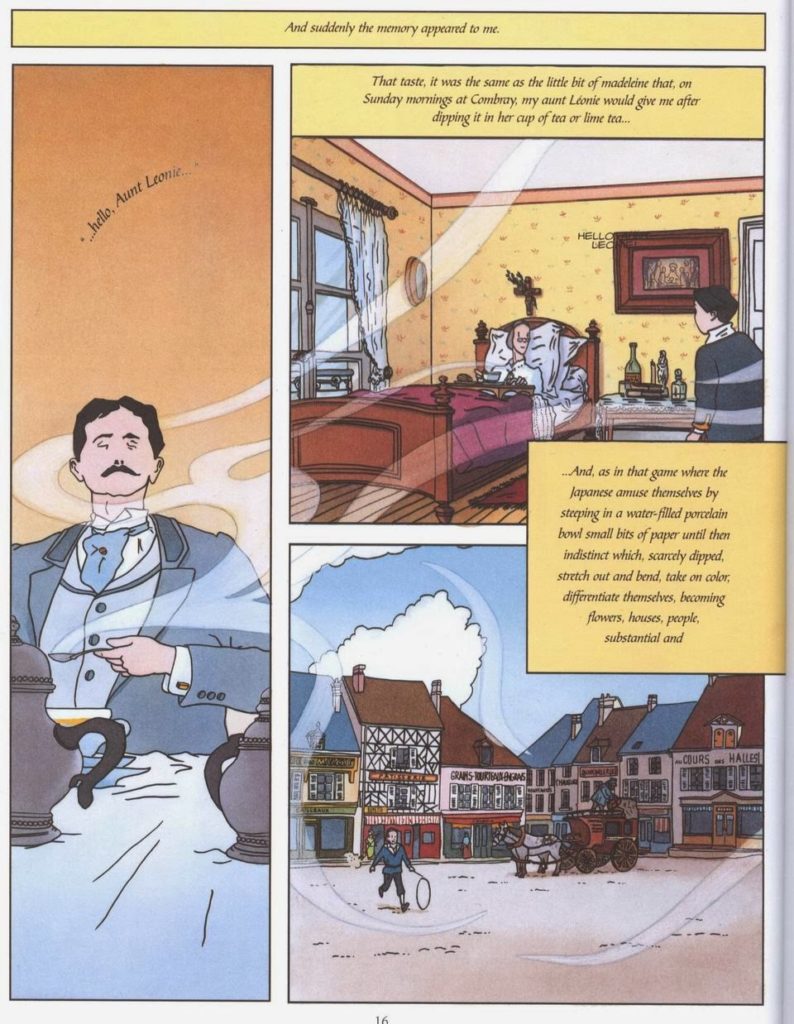

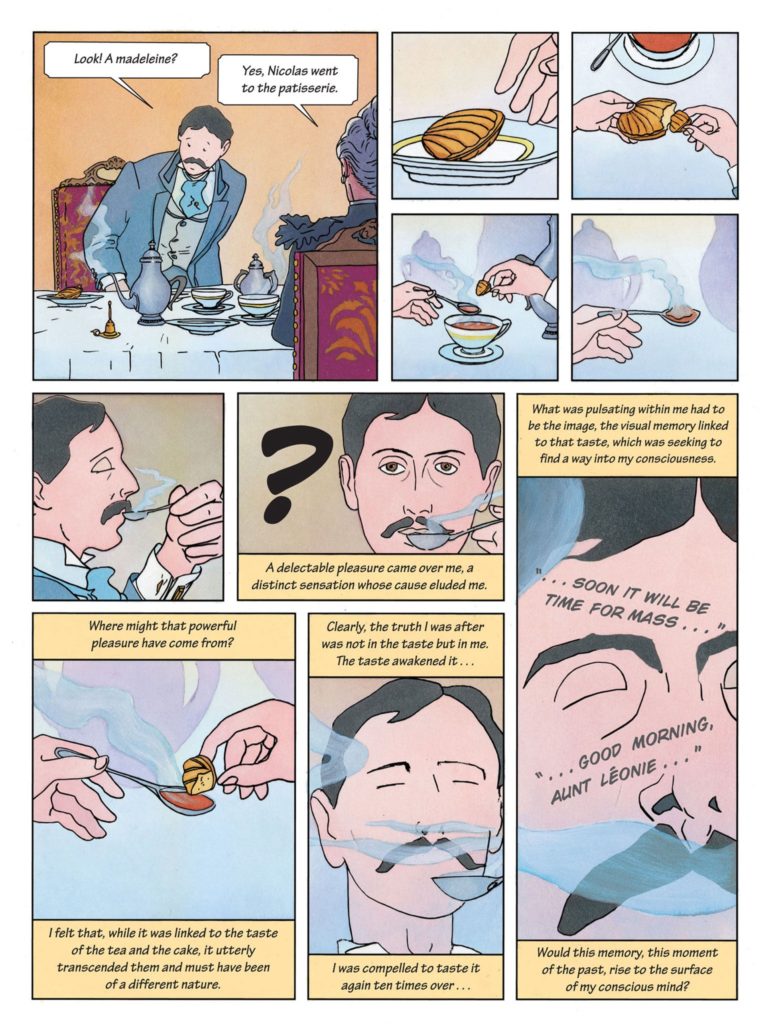

Heuet’s “clear line” approach to illustration leads to some panels of startling beauty, even as he manages to retain a sense of the particular and emphasize the importance of seemingly trivial details that will eventually trigger specific emotions in the narrator. Laura Marris also does a commendable job as translator, extracting the essence of Proust’s prose to fit these beautiful images and sometimes, wisely, letting the illustrations do all the work without words.

Together, they also manage to convey the poignancy of this volume that comes from the narrator’s relationship with his grandmother. Her death in the next volume makes the time shared with her grandson here particularly bittersweet, and Heuet treats the subject with sensitivity.

When the first graphic volume of this epic appeared in 2015, the American academic and translator Arthur Goldhammer described it as “a piano reduction of an orchestral score.” One can treat that statement as simplistic, or recognize it as praise of a high order. Ultimately, what Stéphane Heuet has managed to do is nudge more readers towards what has always been a daunting classic. For that alone, he deserves to be applauded.

![[REVIEW] MOON KNIGHT FIGHTS FOR TIME ITSELF IN ‘MOON KNIGHT ANNUAL #1’](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/clean2-150x150.jpg)