In October 1966, Ray Bradbury and his daughters sat down together to watch the Halloween special It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, Schultz’ second holiday-themed special following the success of A Charlie Brown Christmas. And… none of them liked it. They were all disappointed that The Great Pumpkin didn’t show up; there was something missing and to them it wasn’t a proper Halloween film at all. Bradbury commiserated with animator Chuck Jones over lunch a few days later, agreeing that though they admired Schultz, his special didn’t quite capture the true essence of Halloween.

It’s an important holiday after all, one that allows us to freely explore our obsession with the macabre and the unexplained, to experience “the rawness and nearness and excitement of death” as Bradbury put it. And children, he claims, are fascinated by death. As a writer, he’s always understood that young readers shouldn’t be talked down to, that good youth fiction is written for children, not to children. Kids love Halloween because it’s a celebration of all the stories that offer them a glimpse into the dark, forbidden places. Facing that darkness, that horror, is a very important part of existence.

“We just can’t face nothingness. We’ve got to make something of it. So we can hold death in our hands for a little while, or on our tongues, or in our eyes, and make do with it.” – Ray Bradbury

But by 1966, Bradbury already felt that Halloween wasn’t what it used to be. Kids went trick or treating without really knowing why they dressed up, without exploring the dark mysteries of this spookiest of nights, only intent on getting the largest haul of candy in exchange for doing absolutely nothing. There were no tricks, only treats.

At lunch that day, Jones recounted to Bradbury how a young boy dressed in a rabbit hood had come to their house on Halloween only to find they had run out of treats. “It will have to be a trick,” Jones told the boy jokingly, who said “All right,” and walked straight out onto the lawn to stand on his head. They delighted in this boy’s inherent acceptance of the rules of Halloween, that sometimes you get the trick and not the treat. Somehow the history of Halloween and its purpose had been forgotten, but still its spirit remained.

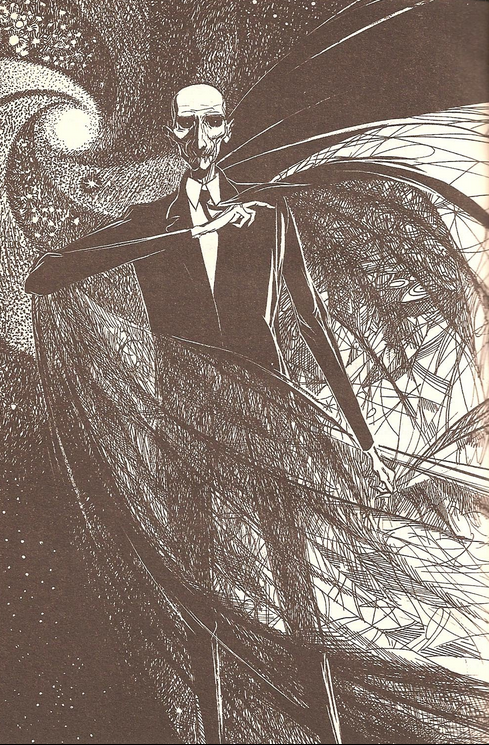

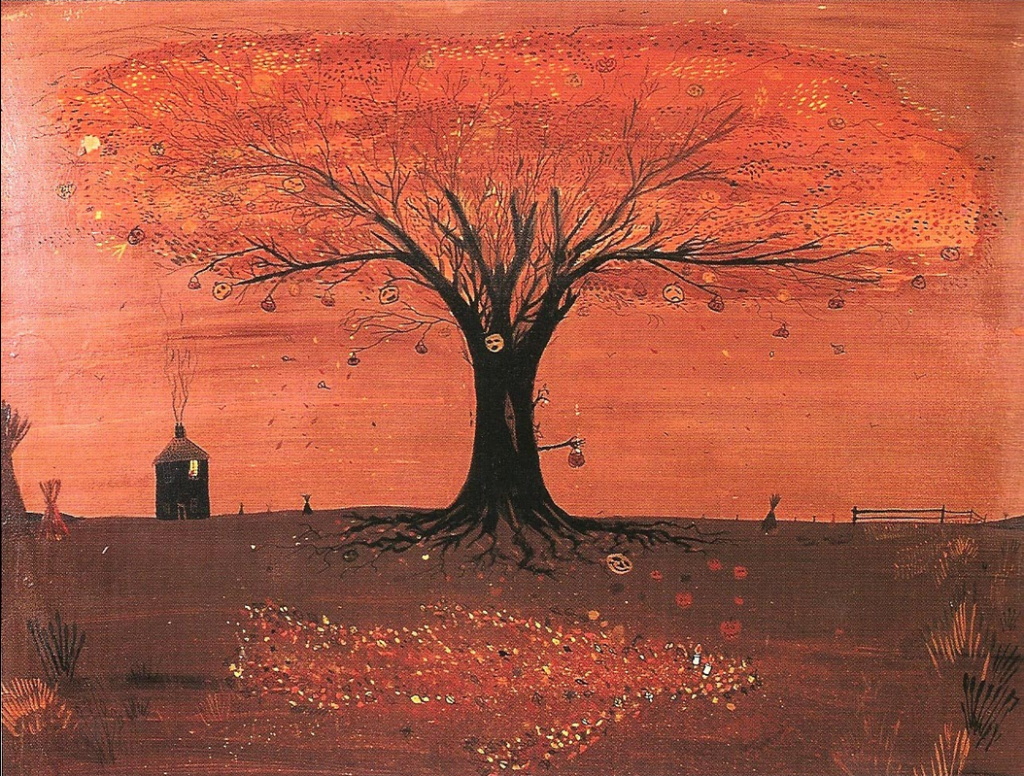

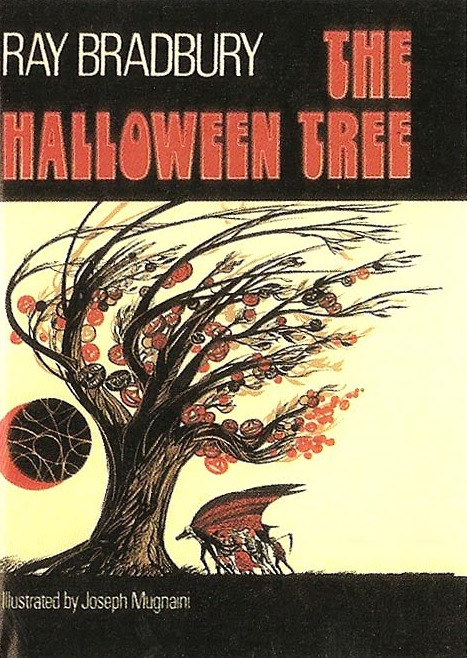

Bradbury brought Jones an oil painting of a Halloween Tree he’d made with his daughters a few years before, a dark, haunting tree decorated with jack-o-lanterns swaying from its autumn branches. In that painting, Jones’ said saw the entire history of the holiday and so he and MGM hired Bradbury to write a script for The Halloween Tree in 1967. Unfortunately, MGM shuttered its animation division soon after, leaving the script unproduced. Bradbury wasn’t able to get it picked up elsewhere and instead wrote a short novelization, published in 1972 with handsome illustrations by Joseph Mugnaini. My first encounter with The Halloween Tree, however, was the 1993 animated film produced by Hanna-Barbara for the Cartoon Network, which was also written and narrated by Ray Bradbury and won a Daytime Emmy for Outstanding Writing in an Animated Program. I re-watch it every year as part of my own holiday ritual that began so many Halloweens ago.

The film is a quintessential Halloween story about a group of trick-or-treaters who are spirited away on a journey through time and space by the sinister Carapace Clavicle Moundshroud. They travel through eras past, uncovering the eerie origins of Halloween in order to save the soul of their best friend Pipkin, who lies bedridden on this hallowed night, about to succumb to appendicitis. Pipkin’s rent is due and Mr. Moundshroud has come to collect, but his friends intend to save Pip’s spirit before it’s too late.

After I finished the film, I remember immediately biking over to the library to reserve a copy of the book. I knew from Bradbury’s poetic narration that I would get lost in his prose and the candid portrayal of dark and creepy subject matter was refreshing to a young reader. It’s the first Ray Bradbury novel I ever read, and certainly wasn’t the last. What struck me most at the time were the differences between the novel and the animated version. Even though the book was a wonderful read, some moments in the story felt peculiar compared to the film, perhaps because I’d seen it first. I only discovered later on that The Halloween Tree had originally been a teleplay, and so went back and forth in its adaptation, each version yielding a more refined and coherent story.

The first distinction is the group of trick-or-treaters, which is paired down from eight boys to three boys and one girl for the film. The likely reason is accessibility; even the kids’ are conventional archetypes in the movie in order to make them more relatable, though their individual personalities are engaging and well-rounded. By contrast in the book, the boy’s identities are hidden by their costumes and most of their personalities are completely interchangeable because of it. Arguably that was the point, but this approach wouldn’t work as well in a kid’s animated feature. The roles of the four friends, Tom, Jenny, Wally and Ralph were also expanded in the movie so that each had something they needed to overcome and their personal connections to their best friend Pip are more deeply explored. The film did a better job of showing the friendship that ties their gang together and brought authenticity to their resolve in making the final grim decision.

Some viewed adding a female character as pandering to ‘gender equality’, altering the nature of a story about boyhood friendship and coming of age. After all, when describing Pipkin in the novel he “hated girls more than all the other boys combined.” Personally, I rolled over that passage without much thought. It’s the only time this aversion to girls is ever mentioned and it doesn’t play any part in the story. As a girl who grew up with three brothers, I took it for what it was: kids being kids, basically it was a non-issue. It baffles me that some people were bothered by the ‘token girl’, when in actuality there was a girl written into versions of the 1967 script; don’t forget that the original painting that sparked the idea was a labor of love by Bradbury and his daughters. Halloween has always belonged in the hearts of all children. Likely she was rewritten as a boy in a witch costume because Bradbury knew his audience and a gang of boys would be much more relatable to a young male reader, which is perfectly fine. When the story was again reworked for the 1993 animated film, times had changed and it made more sense to have a female character added into the mix.

Some may also not be aware that Pipkin, the glue of the novel’s boyhood gang known as “the greatest boy who ever lived”, was actually not in the original script. His character was added to the book to provide more motivation for the rest of the gang to follow Mr. Moundshroud on his Halloween journey. To have a young boy on his deathbed was genuinely upsetting, it’s not a gory death or a scary death, but a real, everyday death. It provided the perfect allegory for the very essence of the holiday, the celebration of life and death, the endless cycle that rules over the seasons and the gods and all manner of earthly beasts. Pipkin’s character evolved further in the movie, taking on a more active role compared to his novelized counterpart. Instead of being pulled through the past by forces beyond his control, he was now actively trying to escape Death by fleeing to the Undiscovered Country with his pumpkin soul, plucked from the skeletal limbs of Mr. Moundshroud’s Halloween Tree. In the book, Mr. Moundshroud had already agreed to take the boys on a Halloween journey when Pipkin arrives, sickly, but eager to partake in the festivities. It’s entirely coincidental that he’s whisked away by some unknown darkness to the same place they were already intending to go. Still, the journey to save Pip’s soul streamlined the plot and, in the film, provided a more engaging dynamic as he sought to escape the clutches of the enigmatic Mr. Moundshroud.

Thanks in part to the amazing voicework by Leonard Nemoy, Mr. Moundshroud is all the more villainous and cantankerous in the film. Instead of merely being their supernatural guide, he’s the antagonist of the story, secretly using the children to lure out Pipkin’s spirit in order to reclaim his pumpkin soul. Mr. Moundshroud is an aspect of Death, if not Death himself, and is annoyed when the children come knocking at his door asking for treats on his busiest night of the year, without knowing anything about the significance of All Hallows’ Eve, He’s much more cunning and sinister, and in the end delivers on his promise of giving them only tricks when he manages to snatch Pipkin’s pumpkin from right under their noses. In the catacombs of a Mexican boneyard, the four friends propose to Mr. Moundshroud an enticing bargain: a year from the end of each of their lives in exchange for Pipkin’s soul. In the novel, Mr. Moundshroud is the one who proposes the exchange, but I enjoyed the ending of the film as it encapsulates the character growth they made over the course of their journey. By offering the bargain themselves the children are facing death head on, “eyeball to eyeball” as Tom puts it, and in doing so, death loses its power over them. It shows that they’ve truly come to understand the meaning and importance of Halloween.

Bradbury is undoubtedly a favourite author of mine. I truly enjoy his penchant for purple prose, he’s one of the few authors I feel can actually pull it off, even if passages sometimes get away from him a bit in The Halloween Tree. His narration in the film was somewhat lifted from the book, but was beautifully refined and captured the nostalgic charm of Halloweens long since passed. You should definitely add this movie to your Halloween watch list. We so rarely think of it as a celebration for the dead, that cultures throughout the ages have done so in order to cope with their own mortality and that facing these truths every year reminds us how to live.

“Hold the dark holiday in your palms, Bite it, swallow it and survive, Come out the far black tunnel of el Día de Muerte And be glad, ah so glad you are… alive!” – Mr. Moundshroud