Leslie Knope finds love, inspires women everywhere, is awesome

By Molly McGowan

“If I be waspish, best beware my sting.”

Katherine, William Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew (II.i)

“If I seem too passionate, it’s because I care. If I come on strong, it’s because I feel strongly. And if I push too hard, it’s because things aren’t moving fast enough.”

Leslie Knope, Parks and Recreation (4.20, “The Debate”)

Leslie Knope is a character I deeply relate to, and I am so pleased that she exists. She reflects my best qualities (thoughtful gift-giving, work ethic) and my worst (myopia, petty competitiveness). Most importantly, I love that the show’s narrative rewards her for staying true to herself, neuroses and all.

She is not your typical leading lady. In fact, she’s an archetypal shrew: stubborn, shrill, neurotic, and unapologetically passionate, qualities that women — real or fictional — seeking romance usually attempt to tone down. It’s a tale as old as time; the shrew must be tamed. In the early seasons of Parks and Recreation, Leslie is perpetually unlucky in love, able to rattle off a selection of her bad breakups:

One time when I was in high school a guy’s mom called me and broke up with me for him. There was another time when I was on a date and I tripped and broke my kneecap, and then the guy said he wasn’t feeling it, so he left and I waited for an ambulance. One time I was dating this guy for a while, and then he got down on one knee and he begged me to never call him again. (3.6, “Indianapolis”)

Although she is a bit hung up on Mark Brandanawicz, romance never takes a primary role in her life. On the singular instance where she compromises her values to impress Mark, she feels so guilty that she videotapes an apology to every female elected official in America (1.4, “Boys’ Club”). Fittingly, Leslie’s ambition propels her forward while Mark’s apathy drives him out of public service.

Her intensity meets its match in Ben Wyatt, initially introduced as her budget-cutting adversary. While Mark begrudgingly indulges Leslie’s harebrained schemes, Ben wholeheartedly supports her and makes serious personal sacrifices because he believes in her, sometimes more than she believes in herself. (Who can forget how he never wrote a concession speech when she ran for city council?) When she makes an important Chamber of Commerce presentation despite a debilitating flu, Ben remarks, blushing, “That was amazing. That was a flu-ridden Michael Jordan at the ’97 NBC Finals. That was Kirk Gibson hobbling up to the plate and hitting a homer off of Dennis Eckersley. That was– that was Leslie Knope” (3.2, “Flu Season”). They even share some weird interests, from Margaret Thatcher/Richard Nixon roleplay (3.16, “Li’l Sebastian”) to macaroni and cheese pizza (5.20, “Jerry’s Retirement”). Ben is a rare man who finds her tenacity attractive, and encourages her ambition while calming her neuroses. In 4.13, “Bowling For Votes,” Leslie’s competitiveness is compounded by her insecurity; when she creates a large binder dedicated to winning over the prospective voter who vaguely insulted her, Ben knows exactly how to calm her down and call her out.

Her intensity meets its match in Ben Wyatt, initially introduced as her budget-cutting adversary. While Mark begrudgingly indulges Leslie’s harebrained schemes, Ben wholeheartedly supports her and makes serious personal sacrifices because he believes in her, sometimes more than she believes in herself. (Who can forget how he never wrote a concession speech when she ran for city council?) When she makes an important Chamber of Commerce presentation despite a debilitating flu, Ben remarks, blushing, “That was amazing. That was a flu-ridden Michael Jordan at the ’97 NBC Finals. That was Kirk Gibson hobbling up to the plate and hitting a homer off of Dennis Eckersley. That was– that was Leslie Knope” (3.2, “Flu Season”). They even share some weird interests, from Margaret Thatcher/Richard Nixon roleplay (3.16, “Li’l Sebastian”) to macaroni and cheese pizza (5.20, “Jerry’s Retirement”). Ben is a rare man who finds her tenacity attractive, and encourages her ambition while calming her neuroses. In 4.13, “Bowling For Votes,” Leslie’s competitiveness is compounded by her insecurity; when she creates a large binder dedicated to winning over the prospective voter who vaguely insulted her, Ben knows exactly how to calm her down and call her out.

Parks and Recreation, with its signature big heart, celebrates its characters’ idiosyncrasies, from April’s morose sarcasm to Jerry’s bumbling anxiety. Andy, April, Tom, Leslie, Donna, Jerry, and Ron could all hypothetically have character arcs centered around losing their unique qualities and a partner who made them “normal.” Ben and Leslie understand and complement each other’s quirks perfectly. Leslie refers to them as “an adorable man with a cute face and the future president of the United States” (4.9, “The Trial of Leslie Knope”), poking fun at their subversion of the Donna Reed paradigm: a quietly supportive wife and hardworking husband. But it doesn’t stop there — not only is the trope subverted, it’s demolished altogether. Having Leslie step into the ambitious husband role with Ben as the accessory would still make Leslie the punchline. The nagging wife/clueless husband is a tired sitcom trope that can look progressive, but still leaves her with both an undue share of emotional labor and a partner who does not challenge or complement her the way she deserves.This trope is delightfully parodied in 7.9, “Pie-Mary”: Ben, running for Congress, participates in an event traditionally meant for candidates’ wives, but suited more to his interests than Leslie’s, and a group of Men’s Rights Activists show up chanting “Free Ben Wyatt!”

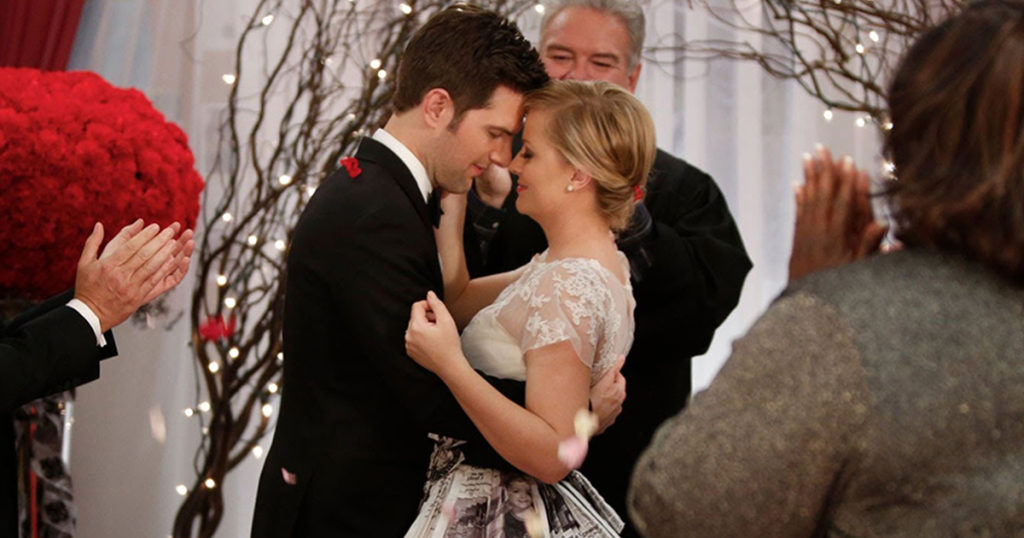

Leslie and Ben sacrifice for and support each other in equal measure. In parallel episodes 4.1, “I’m Leslie Knope” and 4.22, “Win, Lose, or Draw,” Leslie and Ben face major life changes. Leslie decides to run for city council, which would mean that she has to break up with Ben, and she is so verklempt that she runs away to Ron’s cabin in the woods. Despite her independent spirit, she broods over her conviction that Ben will hate her if she goes through with the campaign. In characteristic solidarity, he surprises her with a “Knope 2012” campaign button, taking the pressure to end the relationship off of her, and by beaming with pride as she officially announces her campaign. After the election, when Ben is similarly torn about accepting a job offer in DC, Leslie gives him a miniature Washington Monument as a token of her support. These gestures parallel each other, and their eventual engagement, reinforcing the consistent and tangible ways they encourage each other’s ambition throughout the series. On a lesser show, Ann hastily completing Leslie’s wedding dress with career-related paperwork (5.14, “Leslie and Ben”) would be a joke, but Parks and Recreation never shies away from unabashed sincerity. Leslie calls it “the Ann Perkins of dresses,” and indeed it is such a beautiful tribute to the pragmatism and work ethic at the heart of her relationship with Ben. Leslie is notorious for giving elaborate, thoughtful gifts– Ben affectionately complains that being married to her is “like being smothered with a hand-quilted pillow filled with cherished memories” (5.19, “Article Two”) — but time and time again, her generosity is reciprocated. It is incredibly fulfilling to watch everyone in her life love her as much as she loves them.

As beautiful and inspiring as this love story is, I appreciate that the romance never supersedes their other interests, friends, and commitments. A lesser man would expect to be her highest priority, but Ben conflates falling in love with Pawnee with his love for Leslie– “The town has really nice blonde hair and has read a shocking number of political biographies for a town” (3.14, “Road Trip”), and they register for Pawnee Commons instead of conventional wedding presents. In an episode that makes me tear up every time, they plan to invite the entire town of Pawnee to their wedding, and although the two-part wedding episode serves as a centerpiece to the season, is bookended with professional and personal milestones for each of them.

Leslie’s love story perfectly problematizes the conventional wisdom around women like her. In Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, ostensibly a comedy with a happy ending, the headstrong Katherine is subjected to starvation and torture until she submits to Petruchio’s will. At the play’s denouement, she demurely admits “when [a woman] is froward, peevish, sullen, sour, / and not obedient to his honest will, / what is she but a foul contending rebel / and graceless traitor to her loving lord?” (V.ii). Leslie, like Katherine, is a difficult woman. Unlike Katherine, however, she is allowed by her narrative to dream bigger and be bolder– and she finds a man who is with her every step of the way.

![[WORLD LITERATURE] CANDIDE & THE BEST POSSIBLE WORLD](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Candide-2-1-150x150.jpg)

One thought on “In Praise of the Shrew: On Leslie Knope Finding Love”