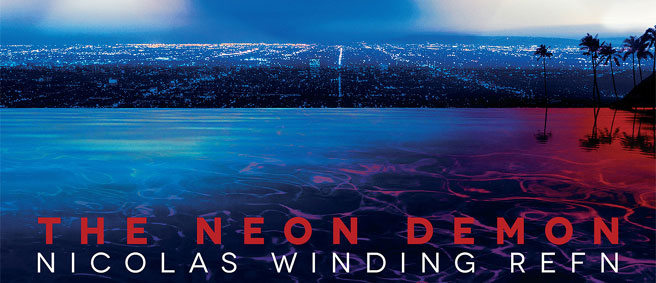

The Neon Demon Movie Review

Review By Thanh Nguyen

A beautiful, young model and an amateur photographer walk into a bar. They meet up with a fashion designer and two other models, one of which is referred to as a “bionic woman” (due to her excessive amount of plastic surgery). The designer disparages her artificial beauty, inciting the photographer to rebut with the naively-sounding truism that “beauty isn’t everything”. In turn, the designer responds: “Beauty isn’t everything. It’s the only thing”.

A beautiful, young model and an amateur photographer walk into a bar. They meet up with a fashion designer and two other models, one of which is referred to as a “bionic woman” (due to her excessive amount of plastic surgery). The designer disparages her artificial beauty, inciting the photographer to rebut with the naively-sounding truism that “beauty isn’t everything”. In turn, the designer responds: “Beauty isn’t everything. It’s the only thing”.

Such is the case in a scene in Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon – one punctuated not with a crude punchline, but with an ugly truth that is lived by the characters in the film. It is a telling scene that is integral to our understanding of what the film is about and how it tries to denote that, which is a grotesque look at the fashion industry through a cinematic exercise of vanity.

Refn deploys an excess of beauty within the film as a result, filling it with eye-candy images that call attention to its own aesthetic and artifice. Shots look like pages pulled from a glossy fashion spread; overtly lit and obviously staged, and featuring a plethora of attractive women that posture like mannequins. Like Todd Hayne’s stylized melodrama Far From Heaven, Sophia Coppola’s lush period piece Marie Antoinette, Harmony Korine’s neon-saturated Spring Breakers, or more recently, Ben Wheatley’s mosaic of debauchery in High-Rise, The Neon Demon conveys a sense of hollow, aimless and vapid lives being lived through the focus on the film’s appearance. Beauty is not used as a distraction, but a device that allow us to see what is most important to this world that Refn depicts. As such, the film never moves beyond the surface level of things.

Characters themselves only convey vague impressions of who they are. The protagonist, Jesse, is a 16-year-old girl who we initially learn very little about, and remains an enigma to the audience till the very end of the film. In her most revealing monologue, we learn that her parents are “gone”, and that she was never good at anything. She moves to LA to become a model because she believes she can “make money off of being pretty”. The film becomes a character study on her mounting vanity and growing ego as she is featured in scene after scene either fully dolled up or getting dolled up. Refn often creates the illusion of Jesse as an eye-catching centrepiece, stripping away her natural surroundings and placing her against an eerie, abstract-like backdrop that is similar in style to Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin. The end result is that we view Jesse as nothing more than a pretty picture.

After following Jesse’s subtle transition from the sweet, starry eyed girl to a self-indulgent model, the film veers towards a violent climax and ending, changing unexpectedly into a Brother’s Grimm-like cautionary fairy tale with all of the allusions to witches and lycanthropic animals intact. The Neon Demon ultimately serves to exemplify the perils of vanity and how fame can eat you alive, although with an allegory that occasionally feels a bit too heavy handed and on the nose. Nonetheless, it’s a daring and bold film that subverts the conventional storyline of the “girl from a small town with big dreams who goes to hollywood” with a nightmarish quality and Lynchian sensibility. The Neon Demon is an experimental, art-house horror that some will find hollow, but will certainly leave an impression as haunting as the beauty that it depicts.