When little girls watch Disney movies, we assume they want to be the princess. Disney stores sell dress-up sets from Snow White to Tiana, jewel-toned dresses with plastic tiaras and tiny jelly-sandal heels, Mulan’s silk hanfu and Ariel’s finned tail. As protagonists, these princess are supposed to be relatable, admirable, role models for impressionable young girls.

But I never wanted to be the princess.

For a long time I assumed that it was because I felt uncomfortable with all the trappings of traditional femininity. But I came to realize that it was more than that: it wasn’t just that I didn’t see myself in the ever-expanding catalogue of Disney princesses, but that I did see myself in someone else. The villains.

Countless people have written about the queer-coding of Disney villains — Scar’s effeminate lisp, over-the-top gay-best-friend Hades, Ursula’s Divine drag looks. Countless people have also written about how this queer-coding is problematic; how harmful a message it is to send to queer children that queer people are always the bad guys, selfish and dangerous and violent. That, just like movies try to teach us not to be bad people, they also do their best to teach us not to be queer.

I am not arguing that that’s not the case. There is historical context, here: monsters have always been used to delineate what is and is not socially acceptable, to illustrate the defeat of those who defy expectations that have been set forth as “normal” and as “moral.”

The stories that serve as bases for Disney movies originated as bedtime stories meant to keep children in line. Even before Hans Christian Anderson and the Brothers Grimm, these stories permeated cultures all over the world, teaching children cultural norms and values; the monsters in each illustrated what happens to children who wander off, children who misbehave, children who do as they want instead of as they should. Stemming from the Ancient Greek tradition that outer beauty corresponds to inner goodness, these stories have always functioned on the implication that the beautiful ingenue is “good” and that those who do what society condemns — the witch, the exile, the outsider, the queer — are ugly. Are monstrous.

But is that all monsters are?

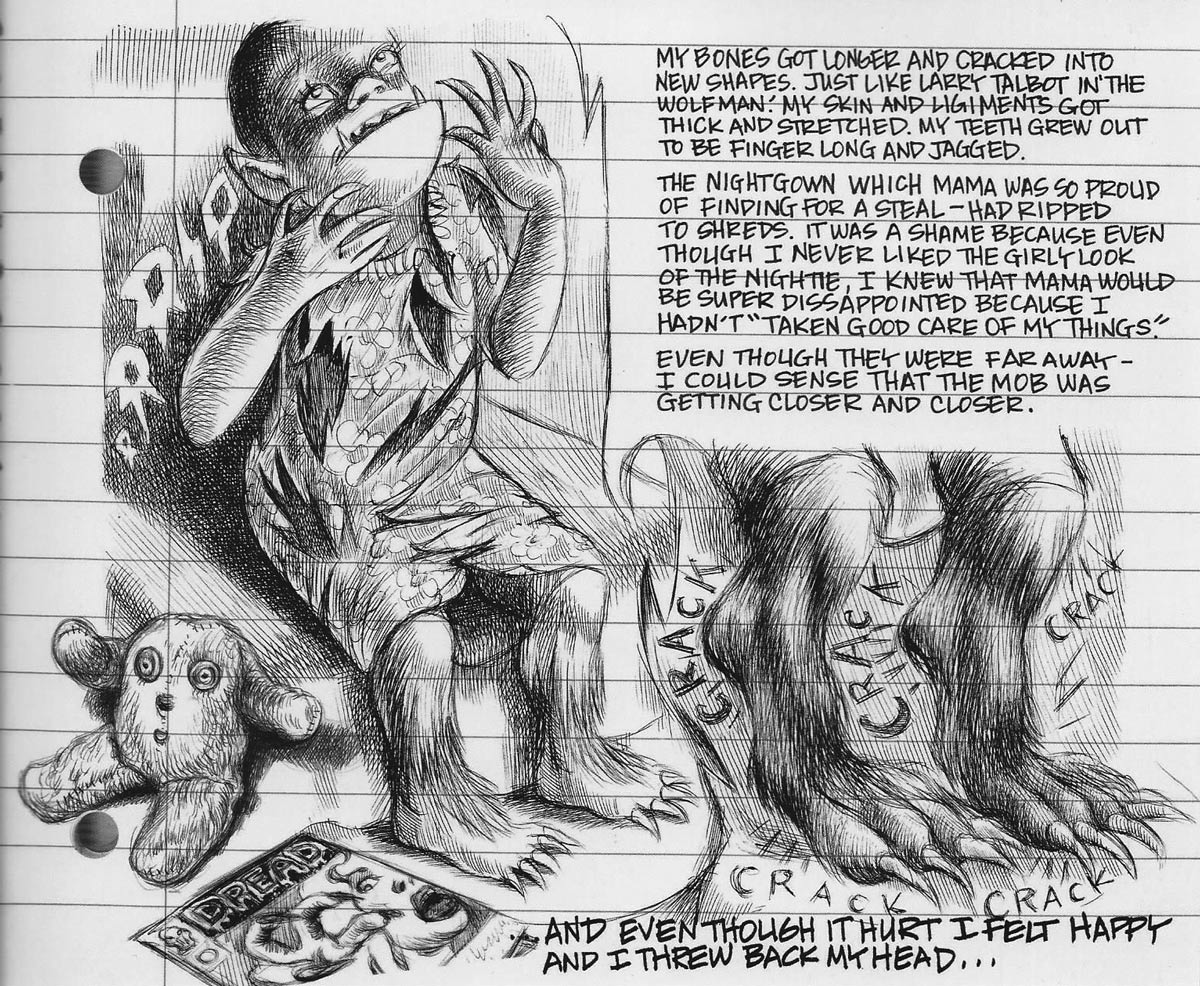

In American cartoonist Emil Ferris’ semi-autobiographical graphic novel My Favorite Thing is Monsters (2017), the protagonist — a preteen girl name Karen Reyes — draws herself as a monster, a sort of Lon Chaney-esque Wolfman creature, complete with hirsute body, protruding fangs, and heavy brow. At one point in the story, her mother begs her to stop drawing herself this way, but she refuses; until the very end of the novel where a hard look at her reflection in a mirror turns her briefly and unwillingly into a pre-teen girl, Karen is a monster.

There are a number of reasons for her monstrous embodiment, each one manifested in the text: she is from a lower-class single-parent family, she is multiracial, she rejects femininity, and she has romantic feelings for her female once-best-friend, Missy. Her friends, too, are monsters — the aptly named Franklin, an effeminate black boy with a prodigious interest in fashion, carries the iconic features of Universal’s pervasive interpretation of Frankenstein’s monster; Sandy, an abused lower-class girl who may or may not be a figment of Karen’s imagination, is a ghoulish figure; even Missy herself, a sort of proto-lipstick lesbian with romantic feelings for Karen and a hidden interest in monster movies, styles herself off of Dracula’s Daughter in fangs and a gown. They are misfits, all, in the story’s late-60s setting, and it makes them monsters.

Karen is at home in her self-assumed monstrous identity; she revels in it, more confident in her skin when it is the skin of a monster than that of a scared pre-teen girl. And that confidence, which allows her to navigate the world on her own terms, to meet it face to face instead of hiding in the shadows, is the same measured confidence that I felt as a pre-teen, facing an eight year tenure at an all girls’ school, not even sure if I was really a girl at all.

Me and my friends were the monsters, in those halls. We passed notes featuring drawings of full moons and vampire fangs. Scar’s Be Prepared and Ursula’s Poor Unfortunate Souls were the rotating backdrop to our sleepover conversations about which girls we thought were cute.

Even months before the first books in the Twilight series took my seventh grade class by storm, I was prowling the library for vampires and werewolves and zombies; when my eighth-grade almost-girlfriend stopped talking to me I retreated to the world of monsters, wore my weirdness — my queerness — as a form of armor to hold me together.

Monsters saved me.

But more than that, I think monsters taught me to broaden my horizons, to see the world for what it was rather than for what society wanted me to see. Sure, they were ugly; sure, they were “evil.” Sure, I was a weird outsider kid for a thousand and one reasons.

And yet, what is beautiful about monsters is that, amidst all of the racism, misogyny, homophobia, and behavior-policing that went into creating monsters, what survives of these stories, what is remembered hundreds of years later, is the monsters themselves, resurrected in story after story, their meanings always shifting but their forms never truly dying.

That’s the message that I took away from these queer-coded villains and monsters as a kid — not that they were evil, not that they were reviled, not that they were ultimately defeated by the forces of good, but that they seemed to be universally accepted as the best characters in these movies. Everyone loved the bad guys; they got the best songs, the most depth of character, the best motivations. Even when they were ostracized from their societies for their non-normative behavior, they held firm to their own personal convictions.

Modeling myself after them may, in fact, have something to do with the birth of my socialist-leaning politics, question-everything attitude, and fierce feminist streak. After all, Scar was a Marxist revolutionary who killed his brother to facilitate an anti-capitalist coup; Maleficent was retconned into a rape victim seeking vengeance on the man who betrayed and broke her. I learned, from a young age, that by being confident in my queer identity I was something else, something other than my peers, in the same way that the monsters and villains always were. I was not just gay, I was not just bisexual: I was queer, with all its trappings and baggage and radical defiance.

It’s the difference, I think, that Sue Ellen Case illustrates in her article “Tracking the Vampire”:

“The queer, unlike the rather polite categories of gay and lesbian, revels in the discourse of the loathsome, the outcast, the idiomatically-proscribed position of same-sex desire. […Q]ueer revels constitute a kind of activism that attacks the dominant notion of the natural. The queer is the taboo-breaker, the monstrous, the uncanny.”

Alignment with the monsters and the villains, alignment against the beautiful heroine and protagonist who did what she was supposed to do, meant that I learned at a young age that there was a world of possibility beyond what was expected of me. It meant cultural norms and expectations held very little clout as I developed my own sense of morals and politics. It taught me to listen to the points of view of the downtrodden, the outcast, and the socially maligned; it taught me to value the viewpoint of the disenfranchised, to distrust the idea that the voice that spoke the loudest always told the entire truth. It taught me to build and define my own moral convictions, rather than to accept the ones society handed to me whole-cloth.

The queer monsters of my childhood didn’t teach me how to be queer, but they did teach me how to find all of the beautiful possibilities that being queer entailed. And I think, at the end of the day, being one of the monsters is a whole lot more fun, anyway.