From Fallout, Dragon Age and Final Fantasy to another well-received and recent open-world adventure, Horizon Zero Dawn, the chisel-jawed face of heroism is ever present in one form or another – literally. Even with the advent of character creation, which allows players to painstakingly craft their protagonist’s appearance (height, weight, age, hair, eye, skin colour, even, as I have witnessed, the size of their package), the male option is staunchly stereotypical.

Forget having a fat, short, or even vaguely androgynous protagonist – if he doesn’t look like the epitome of an eighties action movie start at the height of his career, he’s not the hero game developers are looking for. Maybe this has to do with the fact that much of video game culture developed alongside the he-men of the aforementioned 80s, when characters in mainstream North American comics and action-adventure films capitalized off of cisgender heterosexual male fantasies.

As you can probably tell, this was (and is) all disappointing to someone like me, a non-binary trans person who can’t be bothered to consume any kind of content unless one or more characters are canonically LGBTQ+, or can easily be construed as such.

So let’s think of Link, then (which I do often). Here’s a bit about Nintendo’s ideal hero-type: he’s deemed as lazy, gluttonous, awkward, too short, too scrawny, and too quiet. He loves to sleep, to eat, and to avoid (in many of the games) the duties assigned to him. He’s prone to disobeying or obeying too diligently, he never seems to arrive on time, and he often seems to prefer the company of animals over other people. Not exactly hero material, and yet here Link is, three decades later, one of the most recognizable video game heroes in history. He doesn’t ever leave these rather unheroic traits behind, either. Though he may become more determined, mature in more ways than one, or realize the importance of his position, he remains much the same.

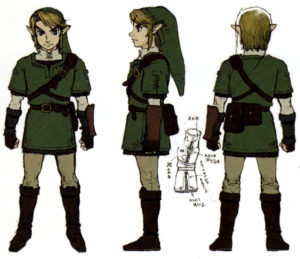

Link’s appearance doesn’t change much, either, a point of contention among a few Zelda fans. Integral to Link are his pointy ears, blonde hair, blue eyes – the very face of fae beauty frequently referred to in Western fantasy. He (usually) wears a green tunic, dons a floppy green hat, wields the Master Sword and bears a shield depicting the Triforce.

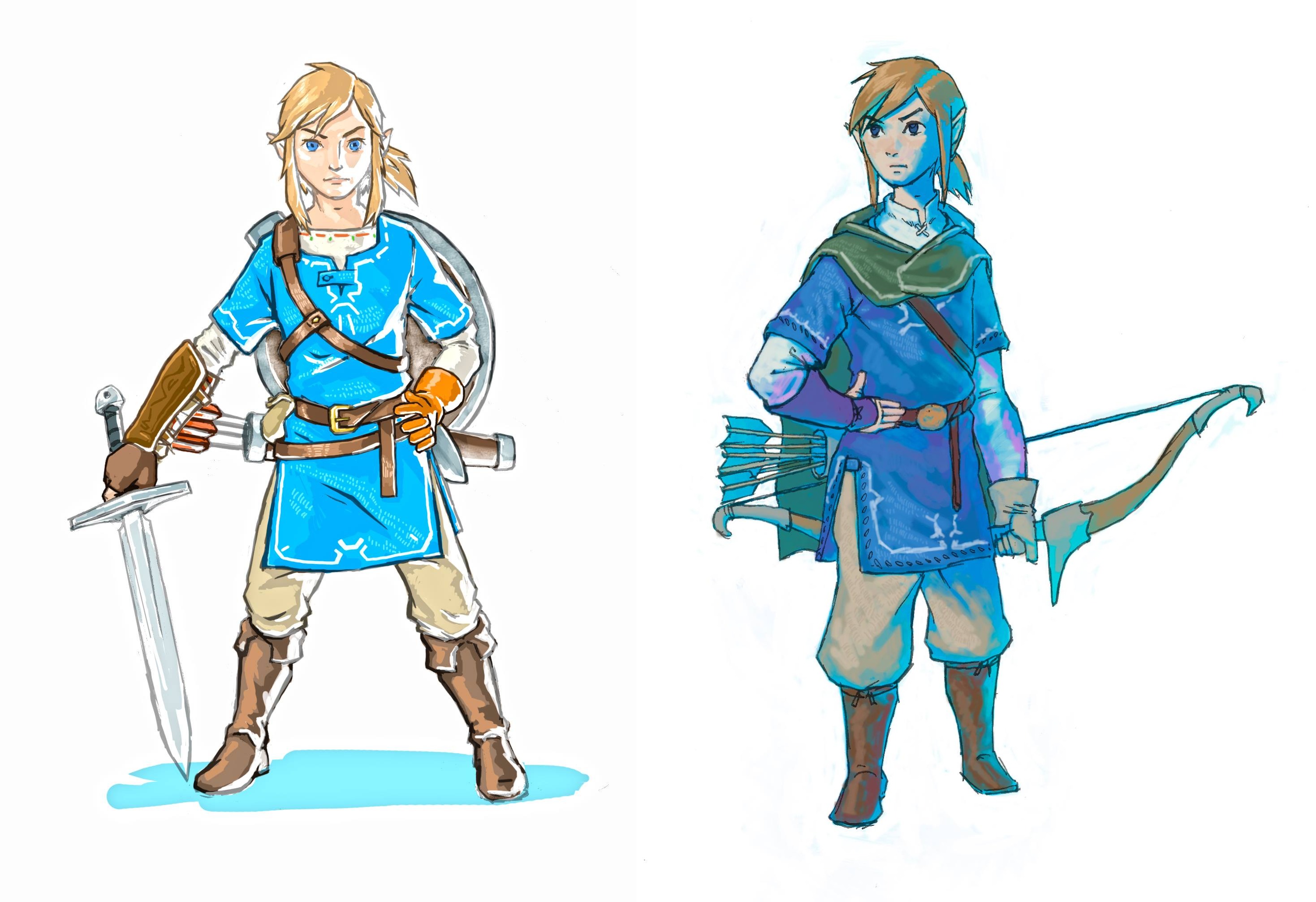

But when Breath of the Wild (2017) was announced, Link’s new design initially shocked those who viewed the game’s teaser trailer at E3 2014. No sword, no shield, a strangely high-tech bow utilizing glowing blue arrows, and – a ponytail? Video game journalists rushed to write their response and review articles, posing the question: is this new Link a girl? The cissexist speculation lasted some weeks. Link’s new appearance was markedly more androgynous than ever: sporting a ponytail, thick eyelashes, and svelte form, he certainly came across as quite “feminine,” even though it was quickly confirmed Link was still a boy – Zelda’s binarist fans, then, could then sit back and relax.

I’m reluctant to continue using the masculine/feminine dichotomy to address the situation here, but this is the language I am left with, language that is used to describe and understand characters and character design in any and all video games.

Language aside, we can turn to producer Eiji Aonuma, who explains that

“…during the Ocarina of Time days, I wanted Link to be gender neutral. I wanted the player to think ‘Maybe Link is a boy or a girl.’ If you saw Link as a guy, he’d have more of a feminine touch. Or vice versa, if you related to Link as a girl, it was with more of a masculine aspect. …I’ve always thought that for either female or male players, I wanted them to be able to relate to Link.”

Maybe, then, it was just a neat marketing ploy. Or perhaps it was just how Aonuma saw Link’s character evolving. Ultimately, though, Link’s appearance – and presumed gender – is up to the character designer/concept artists, who brings Link to life, and then to the player, who fully animates him.

Some early art of Link by illustrator/character designer Katsuya Terada was featured in Nintendo Power, among other official publications, in the late 80s. It depicts him in the same vein as other 80s fantasy, drawing a clear line of influence from North American comics like Conan the Barbarian and Red Sonja, among others. Walk into any used bookstore and you’ll see covers bearing muscled men wielding swords and women, taking up arms against some monstrous evil.

In these illustrations, Link looks older, haggard, haunted by his journey, bullied by monsters, and exhausted by his duty, but he’s recognizable as Link. Still, those jarring colours, deep shadows and “adult” look are very different from the Zelda we recognize today: bright and welcoming, despite the danger that lurks within green fields and colourful towns.

Twilight Princess (2006), however, returned to Zelda’s 80s fantasy roots with a muted colour scheme and an older, more “traditionally” masculine Link. Concept and promotional art pictured a broad-shouldered young man with a sharp face and furrowed brows; someone harrowed; someone who had seen some shit and lived to tell the tale. Ironically, this iteration of our beloved boy was the one I found myself most drawn to.

Past the concept and cover art, into the actual graphics of the game, he looked… different. Softer. Dirty blonde hair, wide blue eyes, (aside from one iconic scene) wearing layers and looking all the world like a farm boy who was dragged into a mess of a world much more dangerous than he had ever imagined. That’s the Link I connected to: someone who looked so distinctly out of place that he couldn’t be anyone but the protagonist. It was hard for me to reconcile this with my own understanding of gender at the time: that to have a gender was to fit in, to follow rules, to look, for lack of a better phrase, the same as everyone else.

As a gender-dismissive preteen who was more invested in fiction than reality, Twilight Princess certainly helped me to see that not everyone had to fit into a box. The binary of rugged hero/damsel in distress is largely absent from Twilight Princess, as well as the earlier Ocarina of Time (1998), where Link is aided by Zelda herself in a masculinized disguise, or in Wind Waker (2002), where she takes on the tomboyish persona of Tetra, a pirate captain and high-seas adventurer who first aids Link in the doomed rescue of his younger sister.

The androgynous characterization continues in characters like Impa, who evolved from nursemaid to chief of Zelda’s royal guard to leader of her people; like Fi, who is the graceful and observationally cutthroat anthropomorphization of the most powerful sword in Hyrule in the series’ origin story, as told through Skyward Sword (2011). Link, too, is subject to such a blend of traditionally masculine and feminine traits. However, his androgyny reached in a rather egregarious element of Breath of the Wild, in which he must don “women’s clothing” to traverse Gerudo Town, known for its tradition of only allowing women to enter. He does so with much success.

While this aspect excited those like me who were deeply invested in Link’s diffusion of the binary, it soon took a rather transphobic twist: the player, in order to get these clothes, has to essentially out a transfeminine NPC in order to get past those gates in what is called a “disguise.” Link, despite his gender ambiguity (enforced, of course, by a non-binary player like me), is complicit in this. It’s certainly a less than ideal situation, to say the very least.

Though many NPCs say the clothes suit him (and Link certainly does look lovely in delicate shades of blue and gold), it doesn’t make up for Nintendo’s insensitive treatment of everything they had apparently wanted to do with Link, which was to make him relatable to everyone who picked up a controller and stepped into his shoes.

As a non-binary person who has appreciated Nintendo’s efforts to keep Link’s androgyny alive and well, it felt like a slap in the face. Presuming that everyone is simply “performing” their gender or donning a “disguise” is one of the most dangerous arguments against transgender people, and is still prevalent in today’s transphobic rhetoric.

But if Link doesn’t have to abide by binarist rules, then neither do I. He is, after all, an avatar. With that, though, I am wont to be reminded that projecting isn’t the same as seeing, and making representation isn’t the same as representing. But Legend of Zelda’s strange dance with Link’s gender identity is at odds with his current gender presentation. Though Nintendo claims he’ll always be a boy, I can’t help but wonder how his character will continue to change.

![[BLU-RAY REVIEW] ‘THE RHYTHM SECTION’ IS A TENSELY INTIMATE SPY THRILLER](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/rhythmsectionposter-150x150.jpg)

![[REVIEW] THE IMMORTAL HULK: FLATLINE #1](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/immortal-hulk-feat-150x150.png)