The Hmong (pronounced moh-ng) are an ethnic minority based in Laos. During the Vietnam War, the CIA recruited the Hmong to help fight and guide them through the jungles. Known as the “Secret War,” many Hmong were left behind when the US pulled their troops from the war. The Hmong were then aggressively hunted down by the Pathet Lao for helping the US. However, through wise leadership, the Hmong were slowly relocated to American soil in the ’70s and ’80s, where they began new lives. Throughout all this pain and change, the Hmong have stayed resilient, and no one embodied that more than Yia “The Bull” Mua.

Growing up in California during the ’90s, Yia Mua developed and honed his muay thai kickboxing into a spectacular career. Unfortunately, Yia’s life was unexpectedly cut short at 34 years old due to liver cancer. The Bull (2020) is a celebration of Yia’s life, an exploration of his trials and tribulations, and a reminder to love unconditionally. Below, I got a chance to speak with the film’s director, Lu Vang.

What inspired you to make this film?

Vang: One of the reasons why the film took so long was because I took a year off. In 2017, Valley PBS reached out to my friend Lar (who headed HmongStory 40 with some other folks) and me and wanted us to put together a Hmong documentary on the Secret War. During that time, I think Ken Burns had put together this week-long series on the Vietnam War, and he didn’t cover anything on the Secret War. Valley PBS was like, “Lar, you’ve been doing all this work for HmongStory 40, why don’t you put something together?” So they fronted half the money, and then Lar had to raise the other half. We ended up working on that documentary in 2017, but once I finished that, I was like, “I gotta revisit Yia’s story.” And, surprisingly, my friend Ge and Kapria, Yia’s sister, started working on the documentary by themselves, so I thought, “Once I finish this Valley PBS documentary, I’m going to see if they need any help.” As soon as the Valley PBS documentary was done, I transitioned right into helping them in 2017.

But I actually took a year off in 2019. A lot of the messages in the documentary about following your dreams and letting courage drive you forth to get past all the things you’re uncomfortable with? I forced myself to make something of all the years I’ve been freelancing by myself. I’ve seen how far it can go on my own, so in late 2018 and into 2019, all I did was work on building a company. I’ve had my own production, StoryCloth Films, for a little bit. That was just solely me by myself. But then StoryCloth Media was the company that I started along with my buddies, Brandon and Nenick. We were figuring out how to build a business, where we want our customers to come from, and the type of work we want to be involved with. We spent a good year just doing that.

Who was the one that most advocated for Yia’s story to come out?

Vang: No doubt, Kapria. She was really the force behind us all coming together to help her tell Yia’s story. She made a promise to Yia on his deathbed to keep his legacy alive, and I don’t think she knew at the time what she was going to do. She just knew that she wanted to do something. The documentary only came up because Ge had approached her. I think initially it was going to be a mini-documentary of some sort, like 15-20 mins, or whatever Ge can put together. So he and Kapria, they initially started it off, and I came on board a little later. But Kapria was the core; our north star. We were looking to her to make sure that everything we were doing was in alignment with what her mission was and what she wanted to get done. So it initially started with her, but then we all collectively joined in to deliver this thing.

Watching the film, it has a lot of unseen footage. Was any of that difficult for you to find?

Vang: We didn’t know where to start. We knew Yia had movies out, but half the stuff I ended up with, I’ve never even seen. Like honestly, I’ve seen one of Yia’s movies, maybe two, including Diam Duab (2010). Before that, I didn’t know where any of this stuff was, so the only approach was, “Let’s source our networks. Our friends and family, whatever they have, make sure we get our hands on it.” It’s partially why we didn’t monetize the film, because different companies and individuals ended up shooting that footage. We couldn’t track down and figure out all that stuff, so we thought it would be best if we didn’t monetize the film. Just prioritize getting his story out and don’t monetize it, because there are production companies no longer in operation and movies he’s made that are no longer in circulation. We wanted to respect their copyright and ownership over that material. Also, we just wanted to leave it open in a way that everyone could access it.

Is there any footage that you were really excited to have for the film?

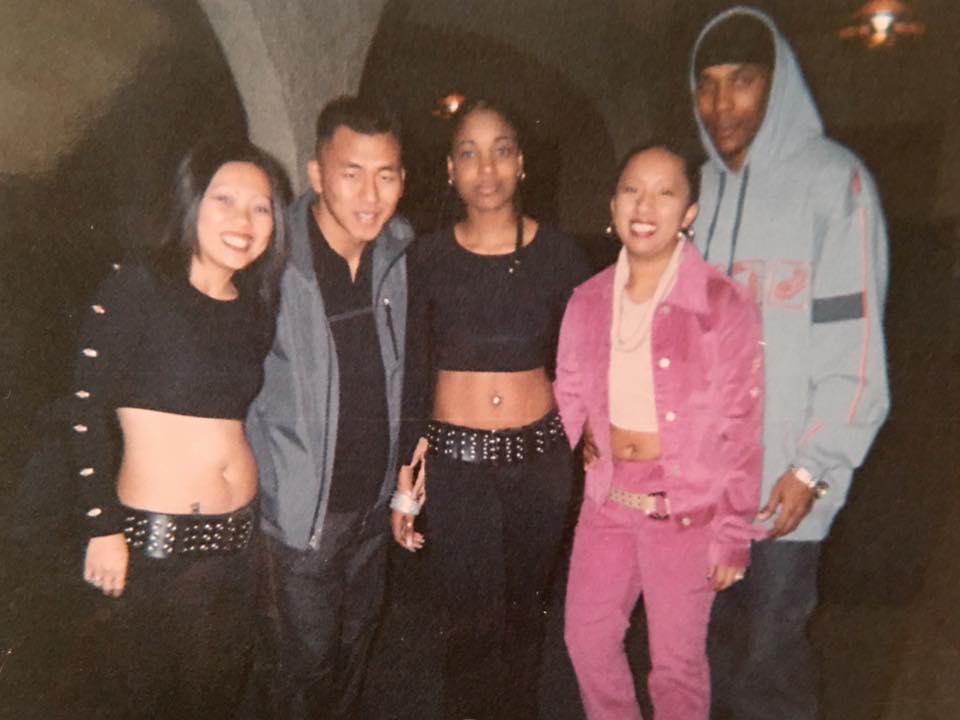

Vang: I didn’t think we could find any footage of Yia performing. I shot the one at the park when they were doing the music video, and we were just kind of messing around. But my uncle Mikey, he works for NBC, I believe, he actually shot a bunch of videos for Paradise, 2U, and Destiny back in the day. He had shot some concert footage, but Yia and them, I think they were the opening act. So my uncle Mikey reached out and said, “Hey, I have all this stuff that I shot,” and he just gave it to me all on a drive, and I was just really amazed to be able to get all that stuff because I’d forgotten about it.

Beyond the Fighter

Yeah, it was really crazy to me how diverse Yia was in terms of the things that he did. At first, you think he’s this really great fighter for the Hmong community, but then you find out he’s also a full-time student, an actor, and also a musician. I guess he’s sort of a Renaissance man in that way. But who is Yia to you, as the director of this film?

Vang: Yia went hard with everything he was doing, and sometimes maybe he didn’t go hard. He just had fun. He was a very adventurous guy, and you saw that in how he approached everything. When I found out they were making music, I didn’t know if they were actually going to stick with it. I just knew that they were really in tune with expressing themselves through it. So to me, in short, Yia’s a hero. And I think a lot of people feel the same about it because of the way he lived and what he stood for, his values and his work ethic. That really inspires people. I think Seth Godin said something about mentors and how you can’t scale them. You can’t get every mentor’s time. Not everybody has access to Tony Robbins without paying a hefty fee, right? But heroes, they scale like crazy, because you don’t need their permission to study them, to follow them, and to learn from them. So to me, Yia is a hero.

In the film, it’s like he always had a smile on his face no matter what. He never rapped before? Doesn’t matter; he’s just going to smile and do his thing. I can see how that can be really inspiring to watch.

Vang: Yia had this intense side where people were like, “He’s like the nicest guy, but then when it goes ‘ding!’ and he’s in the ring, the shit’s gonna hit the fan.” But I like that about people, how they can have extreme dynamics. They can be really shy but then so articulate. Or maybe very humble and then in the ring, just so intense. And so, I love the dynamic of a fully formed person.

So going off of that, when I first saw the trailer, it looked like it was about Yia the fighter. But in the film, you delve into Yia, the person. How important was it for you to portray an almost mythic legend in the Hmong community as a 3-dimensional person?

Vang: I think it’s easy to make Yia out to be this unstoppable, legendary force in our community, but that’s not the truth. Werner Herzog had a very interesting perspective on documentary filmmaking. He’s like, “It’s not enough that you have factual truths; you should be pursuing ecstatic truth.” There’s a certain poetry in ecstatic truth. The only way you can arrive at it is through fabrication, inspiration, and through cultivating these unique details about a person, their life, and their story. It’s up to you to make it into something and say something with it. That’s always been my approach to filmmaking. Yes, we have the facts, but what does it mean, and what do we want to say with it? So it was really important that we had a fully formed representation of Yia, but more importantly, for us to try to look at his life and collectively experience some aspect of it and learn from it. Those were the priorities.

Storytelling, Unconditional Love, and Community

What do you want the newer generation of Hmong people to take from this? I didn’t know about Yia until I saw the trailer.

Vang: There are generational gaps where they don’t know a thing about Yia, right? I think there are a lot of figures in our community where they’re not on everybody’s radar. There are a lot of amazing people, and we just don’t have enough storytellers who are actively prioritizing the telling of those [Hmong] folks and their stories. But more importantly, through the work that we’re doing, I just want to convey across the generations that it’s important to tell our stories. It’s important to give our voice to those stories and not rely on other people to tell those stories for us. But at the core of it, it’s just all love. Do everything that you want to do and do it from a place of love. It seems simple, but not everybody lives by that. It’s like okay, everybody has their spouses, their girlfriends, boyfriends, whatever the case is, and they think love only means a certain range of emotions. But to be able to dive into the type of love that Yia stood for? That’s the most important thing that I think I want everybody to take away from this film. Really dive into what love is, and then do everything from that place.

I think it’s really important what you said about telling stories for the Hmong community. It’s good that you guys are telling this story because, as I’ve said, I’ve never heard of Yia’s story. Now I do, and I think that’s great. But what do you think love meant to Yia when he was here?

Vang: I think there are some commonalities all across the board. You understand what love is from your perspective, no different than myself. But what I am trying to explore when I talk about love is the depth. How deep is your love? How deep is your love for the thing that you’re doing? How deep is your love for the community or your family? And champion that, express it. Show us how strong, how deep, and how long-lasting that love can be. Even when you’re gone, it lives on. That’s what’s compelling to me about the way Yia loved. He loved as if friends were being made, and these were going to be lifelong. He loved his wife as if this was his soulmate. So I think to me, those were my takeaways and my understanding.

Is there anything that was left on the cutting room floor that you wish could have made the film?

Vang: I was director and editor, so I got to make the film I wanted to make. I left a lot for things on the cutting room floor, but those were things that either didn’t fit into the overall arc of the story or I simply didn’t have enough information. For example, it was mentioned that Yia was going through a divorce, and it was happening right when he was dying, so I imagine some people would want to know more about that. The only issue is that we didn’t have access to the subjects who could elaborate on that. There are things like that that we never filmed simply because we didn’t have access to it. And we needed to respect everybody’s space because his kids, they love him and they’re still very close with his family, but they had no interest in being on camera.

And the family, it took them a really long time. They were out of the public eye for a very long time. They made one announcement, and that was announcing Yia’s funeral details, but that was the only time they made an appearance. They were silent for years until Kapria and this project started bubbling up, and that was the first time Yia’s mom and Kapria came back into the public eye. But not everybody was ready, so we had to move forward with the people that we had.

With Yia, it seems like he had a lot of plans for the Hmong community. What do you think he would be doing right now if he were alive?

Vang: Just understanding what was driving him, I think any opportunity that allows him to lift the community up. We talk a lot about this in the film, but it was really instrumental and a part of what was really driving Yia. It was about being selfless in his passions. A passion can be very self-serving, but for him, he found a way to rally people behind his passion. Whether that was in the arts or business, I can still see Yia today being an entrepreneur, starting companies, mentoring talent, and making movies. This guy was about adventure, having fun, lifting people up, and, sometimes in the process of doing good work, lifting the community up. And so I imagine he would still be doing a lot of the similar things he was doing when he was alive.

But I was joking with some of my friends, “If Yia was alive, we would totally be running a company together,” simply because there’s nobody that I know who could outwork Yia. Yia’s just on a different level when it comes to his work ethic and passion. But at the same time, it can also be distracting if you have too many things on your plate, and you’re kind of unfocused, wanting to do everything. I would like to see Yia, if he were still alive, be more focused and have a stronger emphasis on his true calling, eventually. But who knows.

In the companion article by Yia Vue, she mentions how the sport of kickboxing was underdeveloped at the time. You sort of touch on that in the film about how he needed a better manager. If he had more support, how do you think his career would play out differently?

Vang: A lot of it just comes down to business and politics, but for the most part, muay thai [kickboxing] simply isn’t getting the same amount of support, attention, and love as boxing or UFC. I wish muay thai was far along enough that there was an infrastructure there to support rising talent like Yia. Still, I’ve always understood that Yia was a guy who didn’t let the situation dictate his trajectory. He took a lot of ownership in making sure he was doing everything that he could to live out his dreams, and he didn’t always know how to do that in the right way. He didn’t even prioritize getting a manager, and I think a lot of artists, they come across the same challenges today. A lot of our [Hmong] artists don’t have a manager because they can’t afford to pay a manager. More importantly, and I’m saddened by this, people who manage don’t have enough commitment to the artist to just say, “Hey, you’re super talented. I want to manage you.” Even if they did have somebody like that, some of our artists haven’t built up that rapport with somebody like that. There’s a certain amount of trust but not enough that enables us to work and thrive together in a way that we haven’t seen.

Everybody who was around in the ’90s understands that the way we distribute music and make money off of music hasn’t changed a whole lot. Even with the world and industry-changing, some of us are still trying to sell our music at the [Hmong] New Years. But for the most part, what makes our community interesting is that we do have a lot of support. For example, Hmongstory 40 was all grassroots, and for our community to come together like that, I would love to see more of. Even if we don’t have the infrastructure, being able to put traction and community behind our different initiatives is a very powerful thing. To prove it, you only need to look at grassroots operations like what we did with Yia’s documentary. We didn’t have anybody fronting the money and providing us the infrastructure. No, we worked and gained the experience for it. We were simply operating from that place of love that I was talking about. That’s what allowed us to keep going.

Building a Team and Hmong Ghost Stories

So as a Hmong artist, what would your advice be to other Hmong artists who are chasing their dreams and breaking away from the box we sometimes put ourselves in?

Vang: Protege, Yami, Two Cycle, all those guys, they’re my friends, and we all kind of came up together in the sense that we all had our own craft, but we all knew each other. We showed up to each other’s events, and we supported each other. I think the most important thing I can do is just listen to the artists from our community. I value being able to sit down with them and finding out, “What are their challenges?” But I did that for so many years that I know what those challenges are. That’s not to say that we don’t respect and have an awareness of their unique problems, but all across the board, these commonalities I’ve noticed are because I’ve spent so much time with the artist community. So now, I’ve shifted to building and prioritizing the infrastructure. That’s why it’s more important for me now to not only find talent out there to collaborate with and help nurture; it’s important for me to be building with folks like Lar and folks who are even outside of the creative community.

When I was freelancing, a lot of the relationships I had were these one-off things where people would pay me to do a job, I do the job, provide the service, and that’s it. Over the years, I’ve prioritized transitioning those one-off transactional relationships and finding a way to give it depth and finding a way to provide more value and invent on the customer’s behalf, because there are things that we don’t know that we need in our community. There’s no guarantee that a Kendrick Lamar Hmong equivalent can come out of our community, but there are people with talent. If we can give them the type of guidance and development they need to grow into their own, those are many wins.

It comes back to Yia always bringing his team with him. Kind of what was said in the film too was Yia saying, “I can teach you how to fight, and you can teach me a little bit of break dancing.” Just building that community and that support.

Vang: I used to work for this startup, and my old boss said to me, “Everybody wants to build a company with A+ players.” But the reality is sometimes you can’t get “A” players. You just leverage whatever you have. A lot of great companies are built by “B” and “C” players. They have one or two “A,” but a lot of times, companies just have their humble beginnings. You only need to recall that story that Jack Ma told. He came to the states and hired a bunch of PhDs thinking, “Okay, they have PhDs, they should know what they’re doing, and we should be able to build a kick-ass company.” But man, it fell apart. It just didn’t work. And he went back home and rallied up some folks that were down to live at his apartment, and they worked together to build Alibaba.

So I feel the same way. I don’t know how to build a Disney, but I know that if I can put a kick-ass team together, we can do anything. I imagine you [Geek’d Out] have something of a team too, and it might be lonely in that not everybody is going to stick around. People are going to go their own way. That’s why community is so important. At the end of the day, that community that loves your work, that wants to see Hmong films, that wants to see Hmong people rise? That community isn’t going to disappear.

Lastly, do you have any projects you want to plug or anything you’re excited for the future?

Vang: That’s one of the most challenging things I have right now. I’m very good at being able to deliver on somebody else’s vision, because it’s been part of my job to do that, but throughout my whole career, I’ve struggled with finding my personal projects and then championing it. Maybe you can help me with this: Should I do something that’s different from the documentaries or should I make another film? Or do I do this graphic novel that I have in mind? I’m trying to ask myself, “Do I want to do something that’s a little bit self-serving, or do I do another project that’s selfless in the sense that I want to prioritize bringing everybody together to do something that’s beyond myself?” Which one should I prioritize?

But let me tell you about the graphic novel idea and see your take on it. So imagine all the different superstitions that we have in the Hmong community, right? Essentially, it’s me just taking all those goofy superstitions and then remembering what we did as kids. My generation, growing up in the ’90s and ’80s? All the dumb shit that we did as kids, I just wanted to find a medium that was appropriate for me to tell those stories. I figured I didn’t want to do reenactments or anything goofy like that, so I figured maybe animation or graphic novel.

Here at Geek’d Out, we cover a lot of comic books, so if you’re asking me, the graphic novel is a good format because you can basically do anything. You don’t have a budget. You just have to draw.

Vang: Okay, I’m happy you told me that. You can tell people that you influenced me into going this direction. But yeah, I really do want to do something that’s different from what I’ve done. The Valley PBS The Hmong and the Secret War (2017) that was a really serious film. Yia’s film, his mom told me, “Don’t forget to make it funny and fun,” so I tried to inject a little bit of that into the film,. However, for the most part, it was still a really traumatic experience for a lot of people, especially those still working through their feelings and whatnot, so I think I want to do something that’s a little more light-hearted. And there’s a ton of stories from my friends, myself, and from our childhood that I would love to be able to put on the screen or on the page. That’s really where I’m at right now.

The Bull is available for free on YouTube.

Support your local artists.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

![[EDITORIAL] CHADWICK BOSEMAN: THE UNTIMELY LOSS OF A KING](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ChadwickB-150x150.jpeg)

![[LIST] AUGUST STAFF PICKS](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/STAFF-PICKS-1-150x150.png)