“Therefore, dark past, I’m about to do it. I’m about to forgive you. For everything.” -Mary Oliver, “A Settlement”

Content warning: discussion of rape

The “Strength” tarot card depicts a young woman in harmony with a ferocious lion. For a deck that is structured in a gendered, monarchial way, it has always seemed endearingly odd that “Strength” features a woman. The archetypal women in tarot are mythical (such as The High Priestess), metaphorical (such as Queens for each suit), or domestic (such as part of the family in the Ten of Cups.) So I’ve always loved that Strength is a woman. She is a companion of the lion, wearing a shift dress and a flower crown, not in the act of slaying it. In this depiction, strength is peaceful, vulnerable self-assured, and most importantly, not aggressive.

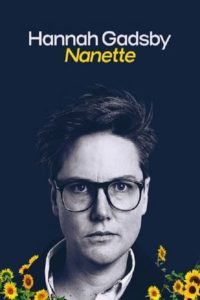

It was this depiction of Strength that was on my mind when I watched Nanette. As Hannah Gadsby herself puts it, “I happen to know that my sensitivity is my strength. It’s helped me navigate a very difficult path in life.” I procrastinated on watching because I suspected that watching Nanette would emotionally destroy me. It was indeed an emotionally intense experience– Gadsby and I have a lot in common: we’re both short and zaftig round-faced butch lesbians with art history degrees (and a deep disdain for Picasso) who are on the autism spectrum and have similar experiences with sexual assault.

Yes, of course, Nanette gutted me, but it also put me back together. Tarot is important to me. It’s a way to look at questions from a different perspective. A way to talk to myself in a way that is productive instead of maddening. Watching Nanette felt like talking to myself. There are some complex issues and emotions she covers that I have rarely heard anyone else talk about, let alone someone in a Netflix comedy special.

Like most women who have experienced sexual assault or rape, I have spent a long time finding ways to blame myself. Gadsby and I share the thorny issue of having been assaulted by men who felt simultaneously titillated and threatened by our butchness. My journal entry the day after my rape ends on the line “I’m just being hysterical.” It took me months to realize that something inappropriate happened. I have been lucky to have a strong support network. There was something incredibly affirming about hearing Gadsby talk about this experience. When she said, “to be rendered powerless does not destroy your humanity… the only people who lose their humanity are those who believe they have the right to render another human being powerless,” my jaw dropped. It was deeply healing to hear it put that way.

The “Death” tarot card is often frustratingly misinterpreted. It’s not a card of doom and gloom, but an acknowledgment that all things must end and new cycles must begin. More often than not, it’s a card of relief.

Gadsby observes that “… stories, unlike jokes, need three parts: a beginning, a middle, and an end. Jokes only need two parts: a beginning and a middle… [Jokes are] not nearly sophisticated enough to help me undo the damage done to me in reality. Punchlines need trauma because punchlines need tension and tension feeds trauma.”

Comedy has kept her stunted, dwelling on pain and struggling to heal. She feels that comedy is the only thing she knows how to do (“My CV is just a cock and balls under a fax number”) but makes the brave and terrifying choice to quit. She is undeniably angry, and while she acknowledges that she has every right to be. She also feels strongly that comedy is not the venue to express that anger. Anger “knows no other purpose than to spread blind hatred, and I want no part of it.”

I often cite Carrie Fisher’s quip “if my life weren’t funny, it would just be true, and that is unacceptable” when I make my dark jokes. It’s often just a way to avoid dealing with the painful truth. Much like Gadsby, I’ve been precocious/weird/funny since I was a child: “it was a survival tactic: I didn’t have to invent the tension, I was the tension.” Nanette made me think very deeply about the way I discuss my own dark past. Gadsby makes the achingly resonant observation.

“Do you understand what self-deprecation means when it comes from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility. It’s humiliation. I put myself down in order to seek permission to speak… I am incorrectly female, and that is a punishable offense. This tension is yours. I am not helping you anymore.”

Likewise, why do I owe it to anyone to make my experiences with misogyny, homophobia, rape, trauma, and mental illness palatable, let alone amusing?

But, regardless of whether she ends up quitting comedy for good, she’s left us with a great gift. Her mission was twofold: to empathize with those who see themselves in her and to encourage those who don’t to understand. Speaking to her straight and/or male and/or gender-conforming audience, she says, “you need to learn what this feels like because this tension is what not-normals carry inside of them all of the time. It is dangerous to be different.”

And speaking to her female and/or lesbian and/or gender-nonconforming audience, she remarks that she would have loved to have heard a story like hers as a child “to feel less alone. To feel connected. [So now] I want my story heard.” I often struggle with pride because, like Gadsby, I “I sat soaking in shame, in the closet.” Nanette made me proud like little else has because I identified so deeply with everything she said. I admire Hannah Gadsby deeply and am so unbelievably proud that we are alive at the same time.