“Furious, fat, fabulous, fantastic

Flurries of funk felt, feeding the fanatics

Gift got great, global goods gone glorious

Gettin’ godly in this game with the goriest

Hit em high, hella height, historical

Hey holocaust hints, hear ’em holler at your homeboy

Imitators idolize, I intimidate

In an instant, I’ll rise in an irate state.”

(“Alphabet Aerobics,” Blackalicious)

Introduction

Maybe it is a bit too early to talk about the mutant metaphor at this stage of our journey through the X-Men comics. However, the idea behind this expression is such a fundamental part of the stories to come, and we have to cover the basics at least before we go any further. Why can white, heterosexual males (plus one woman) stand-in for everyone? The answer to that question may seem simple at first, but the answer has multiple layers and aspects to it, which we will talk about in this article.

Someone to Identify With

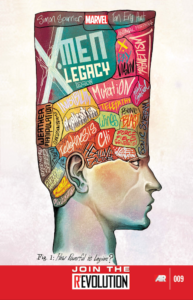

The simple answer would be, that the term mutant does not equal one specific social prejudice, but can be replaced by all or none of them. So it is not that significant if the characters themselves are black, white, man, woman, gay, or disabled. What matters is that the mutant part of them. Or at least that’s an excuse one could use. Of course, mutant is interchangeable with gay, as we have seen in past reviews. Still, their appearance matters as well. The first thing we see on the cover is not that they have powers or that they are mutants. The first thing we notice is that the white man is wielding those powers and because we live in a world where one has to declare openly, that he or she is LGBTQ or whatever in between–otherwise we consider them to be heterosexual. It is the norm.

The simple answer would be, that the term mutant does not equal one specific social prejudice, but can be replaced by all or none of them. So it is not that significant if the characters themselves are black, white, man, woman, gay, or disabled. What matters is that the mutant part of them. Or at least that’s an excuse one could use. Of course, mutant is interchangeable with gay, as we have seen in past reviews. Still, their appearance matters as well. The first thing we see on the cover is not that they have powers or that they are mutants. The first thing we notice is that the white man is wielding those powers and because we live in a world where one has to declare openly, that he or she is LGBTQ or whatever in between–otherwise we consider them to be heterosexual. It is the norm.

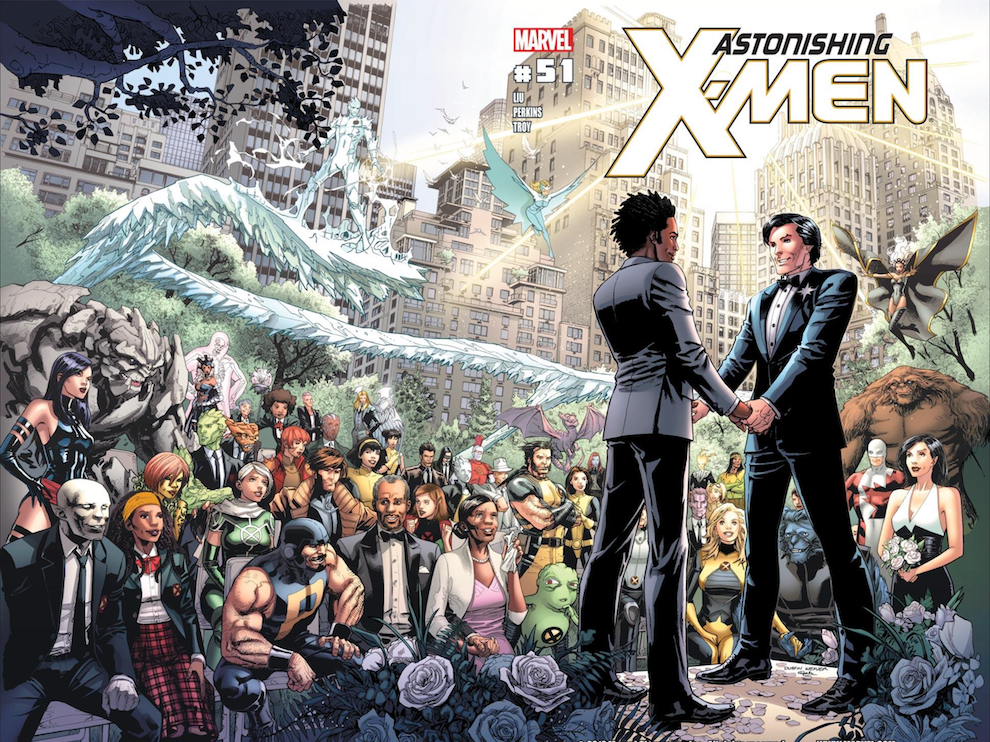

As Dussere writes in his 2017 article The queer world of the X-Men, “The point is not that the X-Men are themselves gay. […] allows the adolescent reader to see his or her own alienation in the experiences of these characters”

One thing that makes the X-Men such relatable characters, at least in my opinion, is their sheer number. There are dozens of characters who have, had, or will have their own series. Every major X-Men title features a team, be it the regular one, the X-Force, or another subgroup. You can pick the one you identify most with and follow them around with different titles. The chances are pretty good that the character you have chosen has at some point in their existence become part of a bigger storyline, or at least featured in numerous titles.

With other superheroes, it is rather binary: either you like them or not. Either you read Batman or Captain America or Superman or Vision or whoever, or not. It is simple. However, the X-Men are and always will be a team. Granted, the latest incarnation of Detective Comics and Superman also feature a lot of different characters, but that is beside the point right now.

The X-Men are much more than just a team. They are a community which sticks together: “All for one, and one for all.” They have more or less matching clothes, take on other names and live among their people. As we discussed earlier, they behave like drag people.

Another thing that makes the X-Men relatable to the LGBTQ community is their mutancy itself. It is a hidden difference. Of course, there are some exceptions like Mystique, Nightcrawler, or, later on, Hank (when he is blue and furry). However, most of them pass as ordinary human beings. This feature is especially true for the first iteration of the X-Men. Later on, their mutations, as the three examples above show, became more and more visible.

Something to Fight For

Question: What do women, the LGBTQ community, as well as black people and other minorities have in common? Answer: Their continuous fight for equal rights. At some point in history, they formed a civil rights movement, with a considerable number of subgroups. They fight for their rights and tell you exactly what they want.

As Darius writes in his article X-Men is Not an allegory of racial tolerance, the X-Men do not fight for anything. Again, at this point, it might be too soon to talk about it, but until I have gathered some more information on my own (by that I mean read a couple more issues), I take Darius’ opinion seriously. He has an intriguing point when he says: “They do not demand representation or an end to discrimination. They do not demand anything.” Up until now, the only time I saw them fight for their rights in politics or similar channels happened during the movies (most prominently in the first one). So far the comics say the public fears them, but the X-Men fight for themselves nevertheless. What do they do to end those allegations?

Granted they fight for the humans and respect authority, but most of the mutants seem to be evil. Moreover, as we saw especially in the first iteration of the team, the mutant community is mostly split “between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ factions” (Darius, 2002). The fact is, that “mutants almost never support mutant civil rights; there is no such noticeable peaceful movement in the comic books even today” (Darius, 2002). What is the reason for that? Darius suggests:

“But it’s hard to implement this in a line of 20 books a month, generating massive profit for the company. Also, the fans of X-Men would probably rather not see Cyclops in Birmingham jail for twenty issues, or X-Men take on more the tone of Stuck Rubber Baby than the easier dichotomy between “good” and “bad,” told with a copious dose of spandex fetishism.”

Another part of this discussion would be the cure for the mutant gene (as it is called in later issues) and the Holocaust references especially during the storyline “Days of Future Past.” But those are such huge topics; I want to discuss them in-depth in a separate article.

For now, we keep in mind that mutant can mean anything that is not right in our society and symbolize any reason for feeling alienated from it. As Darowski puts it: “racism, sexism, or homophobia are forms or prejudice which alienate groups of people, there are many people who still feel alienated from society without being a target of those kinds of prejudice” (2011, p.48).

Somebody to Reinvent

One of the best articles I read regarding Chris Claremont’s run on the X-Men was written by Andrew Wheeler. In his text How Chris Claremont reinvented the female Superhero, he talks about Jubilee, Kitty Pryde, Psylocke, Rachel Grey, Rogue, and Storm: “What these characters have in common is no mystery; they were all written by Chris Claremont, the man whose name is synonymous with strong female characters.”

One of the best articles I read regarding Chris Claremont’s run on the X-Men was written by Andrew Wheeler. In his text How Chris Claremont reinvented the female Superhero, he talks about Jubilee, Kitty Pryde, Psylocke, Rachel Grey, Rogue, and Storm: “What these characters have in common is no mystery; they were all written by Chris Claremont, the man whose name is synonymous with strong female characters.”

As of writing this article, I have just begun to read the Chris Claremont run, but there is something different about the way he handles his female characters already. Ororo, on the one hand, is not called any ridiculous names and MacTaggart, who is hired by Xavier as a “housekeeper,” is not objectified. OK, Banshee is flirting with her, but he is the only one which makes it look like a genuine effort.

Of course, I have to mention Jean as well. In the last couple of issues, up to #103 (where I am currently at), she got to do much more than in the Kirby/Lee or Thomas/Adams runs combined. It is incredible to see the character thrive under the direction of Chris Claremont already. I am curious to see where we go from here and how the characters mentioned above will be introduced to the title.

“The X-Men launched during the golden age of the superteam. Between 1958 and 1964, DC Comics and Marvel launched the Legion of Super-Heroes, the Justice League, the Fantastic Four, the Avengers, the Doom Patrol, the X-Men and the Teen Titans. One thing these teams had in common was that they each debuted with only one woman on the roster. Even that was a step-up from teams like the original Justice Society of America and the Seven Soldiers of Victory, which didn’t have any” (Wheeler, 2013).

The important thing is that Claremont puts women at the center of various stories and “each woman had a different story to tell, and none of them could have stood in place of any of the others” (Wheeler, 2013).

Conclusion

My goal for this article was to talk about the mutant metaphor and how deep the meaning of this expression can be. We are not only talking about the LGBTQ community, which may identify most with the X-Men (that’s just a feeling) but also how the metaphor can mean different things to different people. Lastly, I wanted to give you a little glimpse of what may come next by mentioning upcoming characters and what other people think retrospectively of Chris Claremont’s run. I am sure we will be coming back to this topic in the future and talk about more specific aspects as I mentioned above.

Sources

- Darius, J. (Sep 25 2002). X-Men is Not an allegory of racial tolerance. Retrieved from http://sequart.org

- Darowski, J. (2011). Reading The Uncanny X-Men: Gender, Race and the mutant metaphor in a popular narrative (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.lib.msu.edu

- Dussere, E. (Jul 12 2000). The queer world of the X-Men. Retrieved from: http://www.salon.com

- Sanderson, P. (1982). Interview with Chris Claremont. In Peter Sanderson (Ed.) X-Men Companion I. (pp. 89-122). Stamford: Fantagraphics Books, Inc.

- Shyminsky, N. (2011). “Gay” Sidekicks: Queer Anxiety and the Narrative Straightening of the Superhero. Men and Masculinities 14(3), 288-308. DOI: http://journals.sagepub.com

- Wheeler, A. (Feb 19 1013). How Chris Claremont reinvented the female Superhero [blog post]. Retrieved from http://comicsalliance.com