“He say I know you, you know me

One thing I can tell you is

You got to be free

Come together, right now”

(“Come Together”, The Beatles)

Introduction

In this article, I want to talk about the beginning of the X-Men. We will look at the first 19 issues. They were written by Stan Lee and drawn by Jack Kirby and later on, Werner Roth. How were they published and what are the stories about? Then we will focus on the characters. Who were the original X-Men? How were they portrayed? It is fascinating to look at those over 50-year-old stories. Joseph Darowski talks about an important topic at the beginning of his doctoral dissertation, which I also want to mention briefly: Everything is perceived differently by different groups.

And maybe most importantly: No product has one fixed meaning. It can change over time (at least the primary reading) and is a very subjective thing. In addition to that, we have to analyze those comics as what they are: a product of a different time. Don’t let us use this against them, instead take it as a time capsule and see how the world looked at certain things at that time. These comics are artifacts and reveal social attitudes. Because “society’s entertainment reflects and influences that society” (Darowski, 2011, p. 11).

Beginnings

An interesting thing I discovered during my research is that Marvel could publish only a limited amount of comics per month. Before 1961 Marvel was known as Atlas. At that time they lost their distributor and were forced to join Independent News which owned and distributed National Allied Publications. This company was founded 1934 and would later be known as DC Comics. Marvel’s comics were not that good a seller as the 1950s ended. This may be the reason why their new distributor could easily limit the number of comics Marvel was allowed to publish. This number was initially at eight comics per month. But as the quality of the stories increased, so did the number of comics sold. With that in mind, Marvel was allowed to publish more and more issues. After the contract ended, they joined forces with another distributor and could finally release the amount they wanted.

In a two year period, they only released thirteen issues of The X-Men. Beginning with The X-Men #14, because of the new distributor, they could release the series monthly.

Another thing is that Stan Lee wanted to name the book “the mutants.” Unfortunately, he was declined the name by his publisher Martin Goodman, because nobody would know what a mutant was. Brian Hiatt tells the origin of the X-Men in a Rolling Stone article: After being declined the title “the mutants,” Lee settled with X-Men, because he “figured, they have extra powers, and their leader is Professor Xavier.” In addition to that, he gave them the powers by birth, which meant he didn’t need any fancy origin stories for each character.

Brad Ricca points out in his article Origin of the Species that “the word ‘mutant’ actually was in fairly widespread use at that time, appearing not only in popular science magazines, but in the New York Times, largely in articles concerning atomic age radiation fears [Ricca, 2014, p. 6].” For anyone who is interested in this topic, I can recommend reading the article of Ricca. She paints a compelling picture of the 1950s and 60s, what some scientists wanted to accomplish, and points out, that the idea of a Homo Superior, as Magneto puts it, is not that far-fetched as it may seem. Especially the concepts of Hermann J. Muller are described in detail there.

One last thing about the publication before we move on to the artwork. In the beginning, I was not aware of this, but it makes sense: There is a difference between the cover date and the actual release date. Maybe because I read so many comics in retrospect (be it collected in TPB or a bunch of single issues) and rarely when they are actually released. Nevertheless, I think it is an important thing to mention:

“Throughout this work the cover date on comic book issues will be used to refer to when the comic book was released, though the cover date does not exactly match the month a comic book was published. According to Brian Cronin, in the early 1960s, there was usually a four-month gap between the official cover date and the ship date. In the 1990s two months was made the official gap between cover date and ship date by Marvel an DC Comics. However, there have almost always been variations in the exact difference between the two dates, even within those general guidelines. Because of this difficulty the cover date will be cited as the date a comic was published throughout this entire dissertation [Joseph Darowski, 2014, p44].”

Artwork

The X-Men were not solely created by Stan Lee. A significant contribution came from Jack Kirby and his incredible talent. Today one artist is mainly dedicated to doing one series, drawing one issue per month. “The King” managed to do up to five pages a day and designed the character on the flow, as he drew the stories, Lee gave him [Hiatt].

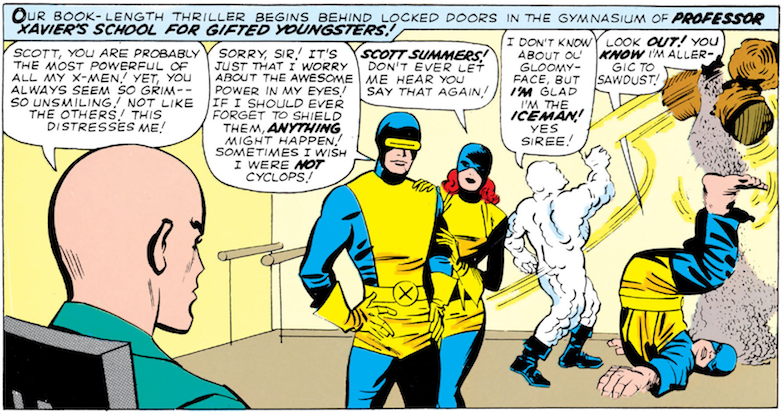

I like the drawings of this time very much. During the training sessions of the X-Men (I will talk about them a bit later on) you get a sense of movement within the panels. The focus is clearly on the characters and Kirby gave them room to act. The background is not that important. Sometimes it doesn’t even exist: just a background color to fill the white space. However, it can also be very detailed if necessary. Each character comes with his or her unique look, gestures and facial expressions. To come up with all of those things while drawing the story is remarkable. Plus the design for the clothing, the rooms and the features of the surrounding areas are simple but effective.

Throughout all of Jack Kirby’s issues (and his successor), you never think of inconsistency or major disruptions. Though sometimes the narration gets in the way of the artwork. In those days, the characters often stated the obvious or – put another way – the artwork and the dialogue/narrator were repetitive. When something is shown in one panel, it is also explained or pointed out by the characters or the narrator. But that is also the charm of those issues.

If you compare it with today’s comics, you get a lot out of these comics. What they say, what they think and how the narrator talks about the characters in combination with the artwork, tells a rich and meaningful story.

But who were the original X-Men?

The X-Men

Scott Summers aka Cyclops, Warren Worthington III aka The Angel, Hank McCoy aka The Beast, and Bobby Drake aka Iceman are the first students of Professor X. In the first issue, after a short introduction of their abilities and who they are, they are joined by Jean Grey aka Marvel Girl.

An unusual aspect of this roster is that they are not a family like the Fantastic Four. This sets them apart from other teams from the 1960s. Although, as Andrew Wheeler points out in his three-part article-series Mutant and Proud, one could assume they were at least cousins because all of them are white, heterosexual, privileged kids. This goes against everything one would expect from a comic book series that is said to be famous for representing women, LGBTQ+ characters as well as black people, and other minorities through a so-called mutant metaphor. The origin of this little group must be read differently than their second genesis in 1975 when Chris Claremont restarts the series.

When we look at the mutant metaphor, we have to look into the very lives of the character and how they represent queerness. Because typically mutants (like queer people) don’t usually come from mutant/queer families [Wheeler].

“Like LGBT people, mutants are not necessarily born of mutants. Their siblings are not necessarily mutants. Their children are not necessarily mutants. They are not born into mutant communities. They are not born into a mutant culture. They are anomalous even within their own families. Like LGBT people, mutants face a heightened fear of being hated by the people who ought to love them the most [Wheeler, 2014].”

But the similarities go further. As drag people, the X-Men take on new names and dress differently when accompanied by fellow mutants [Wheeler]. Sometimes someone has to state the obvious for you, and from that point forward you cannot not see it – as it was the case for me, regarding those similarities of these communities. Big fans, especially when there is a community as big as the X-Men’s fandom surrounding such a medium, we tend to analyze things over. In my opinion, that is often the case, but it is interesting to take those parallels and lay it onto the first X-Men series. I don’t think it was intended by the creators – it is just a coincidence. That is the beauty of stories, and I mentioned it above: different people, take a different meaning from them.

But let’s get back to the original X-Men. Another thing is that at the beginning the characters were mostly white and their mutations were hidden features and not that visible (Beast and Angel both could hide their mutations with gear and clothes) [Darius]. With minimal effort, they all can pass as ordinary human beings and walk around public places, without being detected. Another thing they have in common with queer people. I will talk more detailed about the mutant metaphor and how it changed in the past decades, in a separate article.

The Characters

A recurring theme of Stan Lee’s X-Men run are the training sessions they have at the beginning of nearly every issue. Scott, Bobby, Hank, and Warren are even introduced through one of such sessions. This way we get to see their abilities and determine there camaraderie. How they interact with each other and what their relationship is. It also seems like a very militaristic approach to the story, because Professor X gives them time and again precise timeframes they have to meet. He would say things like “you have three seconds,” “you have exactly 15 seconds” or something like that.

The abilities of the kids get clear very early on. In contrast to them, the Professors capabilities seem to grow or fade – always to suit the story. First, it appears like he just has mental abilities to read minds. But they are sometimes expanded to the point, where he can erase memories. Can he control people like in the movies? This question is unfortunately not answered in those early issues. However, he has another ability that is concerning: astral projection.

The first time I encountered this ability in another way was during the first seasons of the TV series Charmed, where Prue develops this skill. When she does it, she can deactivate her projection at any time, which seems plausible, because it is a mental enhancement of the mind and not fixated on any physical object. The professor’s astral projection, however, must return to his owner, before it can be deactivated. It is also interesting that Magneto seems to have mental abilities as well – at least to a certain degree.

This would suggest that they are somehow related, which would have been a twist, I would not have seen coming. But the professor is related to another mutant: The Juggernaut. He is his stepbrother, and his name is Cain Marko (Cain; as in Cain and Abel – get it?). Cain got his powers from a temple of dark magic and the magical item of Cyttorak. He is an unstoppable force. The two-part story (#12 and #13) are one of my favorite issues from that period. Especially #12 is orchestrated like a horror movie and reminds me a bit of alien. The professor knows what is coming and lets his students make preparations as the Juggernaut approaches. But we never see him directly; he is just hinted at. Jack Kirby did an incredible job. Very suspenseful storytelling and it is a bit frightening as well, although everything happens in broad daylight.

The X-Men #12 is also a great example of the teamwork of the children. They have trained very hard and can now profit from this vigorous efforts.

Unfortunately, Jean Grey is not treated well in the first couple issues. And by a couple, I mean about 14 of them. It starts in the first three issues and from that point on just gets creepier and creepier. Her supposed friends call her gorgeous, beautiful, and have the obsession to touch her vigorously. When she is not around (and sometimes even if she is), they fight each other to figure out should be her boyfriend. It is very frustrating to see her treated that way – like she has nothing to say in that matter. But the most awkward moment of them all happens during a dialogue in the third issue when the professor thinks: “As though I could help worrying about the one I love! But I can never tell her! I have no right! Not while I’m the leader of the X-Men, and confined to this wheelchair!” [Issue #3]

As John Darowski writes in his essay “Evil mutants will stop at nothing to gain control of mankind!”, Marvel Girl has to fulfill different kinds of roles. Be it mother, sister, or girlfriend – she is what the story needs her to be [Darowski]. This is even displayed during the training sessions. While the others do dangerous and physically exhausting exercises (jump around in the room and avoiding flames and pits), she has to handle books (letting them levitate) or works on the precision of her ability (using needle and thread). In case the exercises get too exhausting, she faints or has to be saved by Cyclops. All this in spite of her excellent introduction. The first few pages she manages to handle herself against the boys and is capable of using her powers. She is a confident young girl. This image of her is rendered useless very quickly, as the quote mentioned above of Professor X proves. It is not until the fourteenth issue or so when she is back in control and develops a real personality. In the end, she is equal to the others.

Bobby, Warren, and Hank don’t have such a development during these issues. They train, they handle themselves pretty well during their missions but other than that they don’t have that kind of struggle. Although they each get a personal problem.

Hank, for example, saves a child at one point of the story. But he doesn’t get to be the hero. Out of nowhere a mob literally, attacks him. Before this incident, it is never established, that the general society hates or even knows about the X-Men. Via a direct link to the FBI, the Professor also handles missions for the government. It is not clear, if the world hates or loves the X-Men or if they just decided to ignore them.

Warren, on the other hand, has a more personalized problem. His parents visit the school and are quickly taken prisoners by Magneto. It is another parallel between the queer community and the X-Men. His parents don’t know about his “condition,” so they try to keep it a secret. It is a very emotional issue and the only development he makes, during the first 19 issues.

Bobby can develop his powers a bit. In the beginning, he can transform himself literally into a snowman – covering his whole body with fluffy snow. Because of the training sessions, the snow becomes denser, and he can form a more crystallized “skin” around his body.

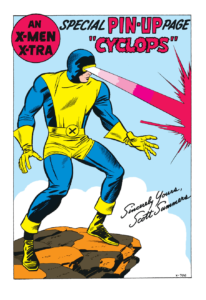

Scott is the one with the most development, I think. At the beginning and during the whole run to be exact, he struggles with his abilities. The destruction his laser-eyes can cause is a real threat. The Professor makes him nevertheless his successor and Scott can handle himself well in situations when his mentor is not around. It would have been great if Kirby and Lee focused the love story on Scott and Jean. They seem to be a perfect couple. But the comments, fights, and behaviors mentioned above make it weird. They could have supported each other.

Friend or Foe

With every issue there comes a new mutant. And with every mutant, recruitment plays a significant role. The introduction of Cerebro, a device that can detect other mutants, was very unsatisfying. In the movies, Professor X has to be connected to it, for Cerebro to work. But in the comics, it’s an independent device. And built into a desk, a wooden desk. There is nothing majestic or impressive about the machine. But you have to begin somewhere, right?

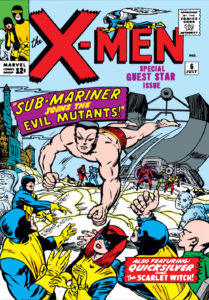

With the question of recruitment and finding other mutants, one cannot ignore some discrimination. They are very rigorous about their new members. A topic that disturbs me is this: We have the X-Men on one side and the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants on the other side. Magneto founded the group, and the initial members are The Toad, Pietro aka Quicksilver, Wanda aka Scarlet Witch, and Mastermind. Again and again, the two teams fight for recruits. The problematic thing about this is that there seems to be no alternative to those two.

Mutants either join them or – well – what exactly? I don’t know what will happen if they don’t want to join the teams, but it always sounds like an ultimatum. Take the Blob for example. The X-Men approach him so carelessly, no wonder he doesn’t want to join either team. After their initial failure, they attack him, and, of course, he fights back. In this situation, the actual threat were the X-Men themselves. And the biggest mistake of their approach is to give him their real names immediately. No secret identities, no costumes or something like that – just their real names and casual clothes.

Here are some examples of characters, Charles and Magneto (we never learn his real name during these 19 issues) fight over: Prince Namor/Sub-Mariner (who bends the laws of physics and not in a good way), Unun (who is defeated by his own powers), Ka-Zar aka Lord of the Jungle (who lives in a secret land underneath Antarktika) and some others. Two of the most intriguing villains of this era (besides the Juggernaut and the Brotherhood as mentioned above) are The Stranger and Lucifer.

Yes, you heard right, they even fight Lucifer himself. Or at least Charles Xavier does. He is the one who put the Professor into the Wheelchair (I like the movie version better; X-Men: First Class) and now he has returned for revenge. In this issue, the X-Men also have to fight the Avengers, because if they defeat Lucifer too soon, a bomb will go off. It is a great issue, and I don’t think that Lucifer is a mutant. But a mere man with a lot of time and recourses. Is he Batman? Just kidding.

The Stranger is also very intriguing. And, interestingly, not even a mutant but an alien.

This eleventh issue is also the source of an exceptionally excellent quote (Attention! Sarcasm!) by a civilian: “Someone get a doctor! Women are faintin’ like flies around here!!” – Beware the two (!) exclamation marks at the end, which are needed for such a great statement. Besides that, the issue is a good read. The Stranger is from another planet who recruits mutational creatures to study them – he takes Magneto and The Toad with him and leaves Mastermind in stasis. This ending was very surprising, and either side cannot really fight The Stranger. He is just that powerful. I could be wrong, but I think this might also be the first issue which ends with a teaser at the end! Or at least it felt more like a cliffhanger/teaser than in the previous issues.

Conclusion

Once you start looking for sources you can use for articles such as this, it can quickly seem like a bottomless pit. One thing leads to another, and you have dozens of essays, books, and articles to read and summarise, so you don’t forget to mention this topic or that clue. I am a perfectionist, and especially the first article in this series should be intriguing.

I wanted to give you an overview of the X-Men’s origin as well as the way they were portrayed. To do that, I focused on a handful of sources and my interpretations of the material. One thing I want to mention though is this: I did not talk about the Cold War references because others already did that way better than I ever could. I didn’t feel like I could bring something new to the table. Instead, it was necessary for me to talk in-depth about the original run from another perspective and provide, hopefully, some inspiration for you as a reader to go back and read these early issues as well.

The next article will focus on the Comic Book Authority, and then we will continue our journey with Neal Adams and Roy Thomas (issues #55 to #66).

Sources

- Darius, J. (Sep 25, 2002). X-Men is Not an allegory of racial tolerance (blog post). Retrieved from sequart.org

- Darowski, J. (2011). Reading The Uncanny X-Men: Gender, Race and the mutant metaphor in a popular narrative (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from etd.lib.msu.edu

- Wheeler, A. (2014). Mutant & Proud (blog posts). Retrieved from comicsalliance.com

- rayrayheyhey (2015). How did DC limit Marvel’s distribution from 1957-1968? Retrieved from reddit.com

- Hiatt, B. (May 26, 2014). The True Origins of ‘X-Men’ (blog post). Retrieved from rollingstone.com

You can find further information on the projects own website: everythingxmen.com

3 thoughts on “Everything X-Men: Kirby and Lee (1963-1966)”