Homer Jay Simpson first appeared on television sometime in 1987. The fact that his is the face that most often comes to mind when the name is mentioned probably vexes students of the classics. The older Homer, alleged Greek poet of THE ILIAD and THE ODYSSEY — also known as texts that form the bedrock of Western culture — simply doesn’t register as often as he ought to. The blame for this rests solely on the access or absence of information. Almost nothing certain is known about the poet: where or when he was born, what he was like, or when he died, as compared to his obese namesake whose visage is as ubiquitous as the donuts he consumes in copious quantities.

This is what makes the work of Gareth Hinds so important. As an illustrator who is possibly capable of working on anything under the sun, Hinds has spent years rendering literary classics into more palatable versions for young readers. This isn’t to say his editions of The Odyssey and The Iliad, ROMEO AND JULIET, KING LEAR, MACBETH, or THE MERCHANT OF VENICE are simplistic. In fact, his predilection for a faithful rendering is often surprising for a medium that often prefers the language of Charles and Mary Lamb to Shakespeare.

The Lamb siblings are to be credited for the fact that their TALES FROM SHAKESPEARE has never been out of print since its first appearance in 1807. It is also testament to Shakespeare’s enduring appeal the world over that his work so readily lends itself to all kinds of adaptations.

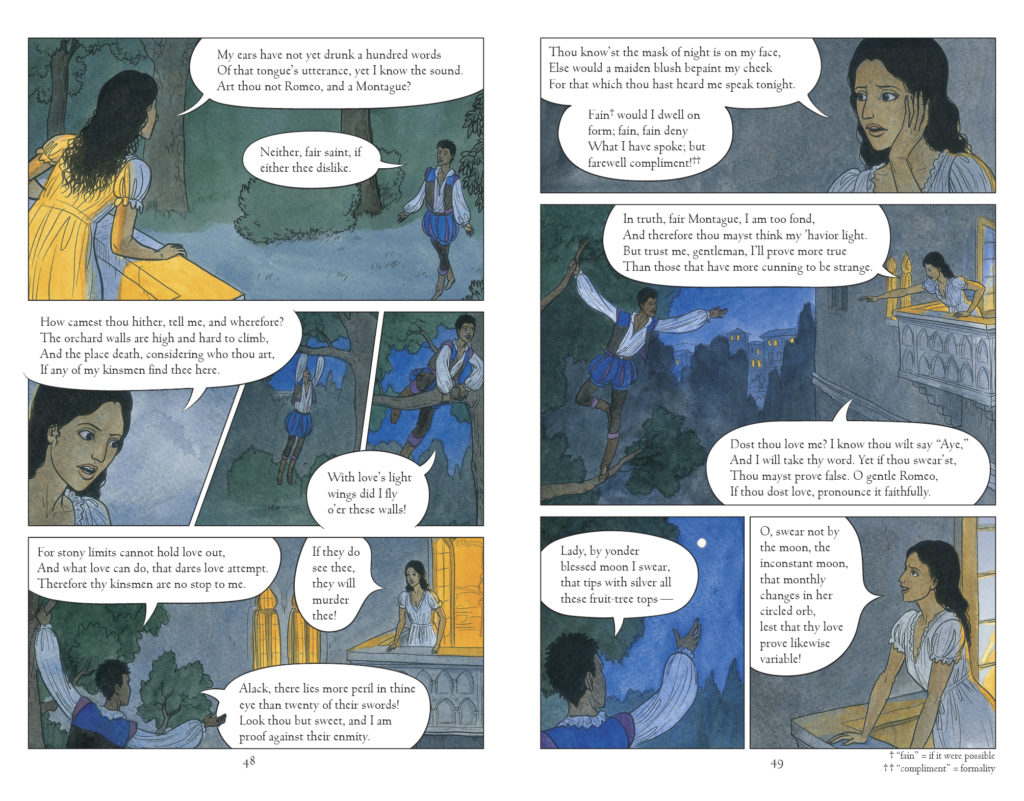

What Hinds does, in his graphic retellings, isn’t simply the addition of visuals to overfamiliar text. His skills as a writer allow him to merge dialogue that is a few hundred years old (or a few thousand, the minute anything in Greek pops up) with sensibilities that are decidedly contemporary. His Montagues and Capulets aren’t from Italian towns that don’t matter, for example, but from countries with political histories that are still being written. The characters are the same, but their backstories are not. It makes for a beguiling mix of ancient and modern that seems effortless, but never is.

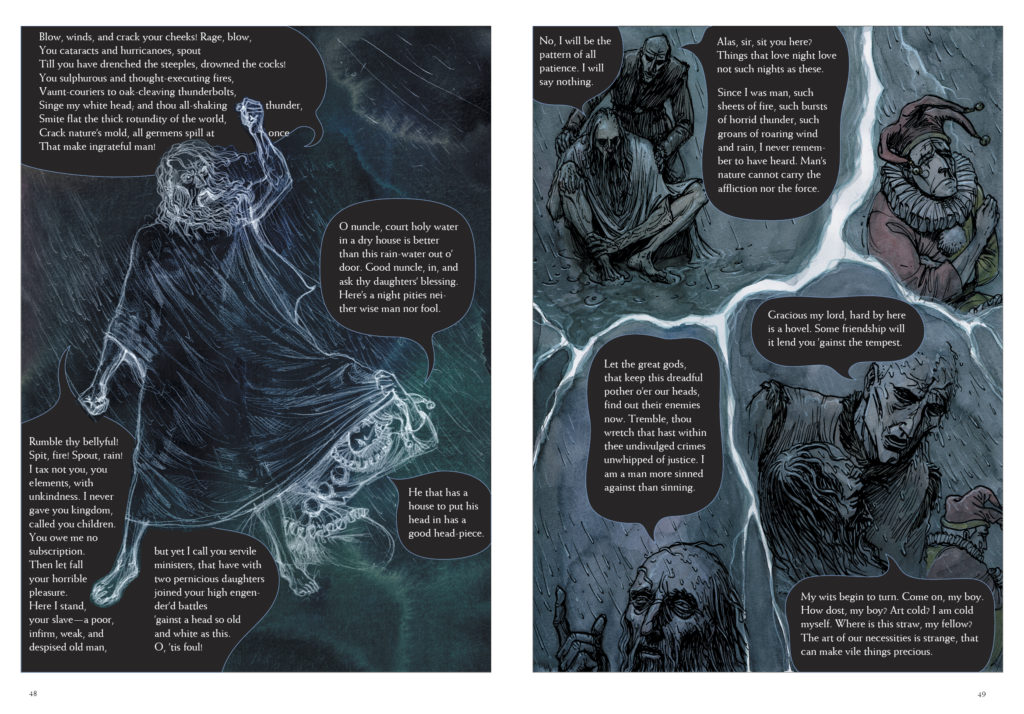

Hinds’s version of Lear is a great introduction to his versatility as an artist because the panels function in much the same way as what is described in literary criticism as the “objective correlative” — a group of things or events that systematically represent or reflect the emotions a writer intends to convey. For Shakespeare, this means placing Lear in a heath as he rages against the gods. For Hinds, the images evolve from bright to dark, sweetness to anger, as Cordelia is asked to leave and Lear begins his painful descent into a kind of madness. It is a powerful complement to the language used in the original play, much of which is deliberately retained.

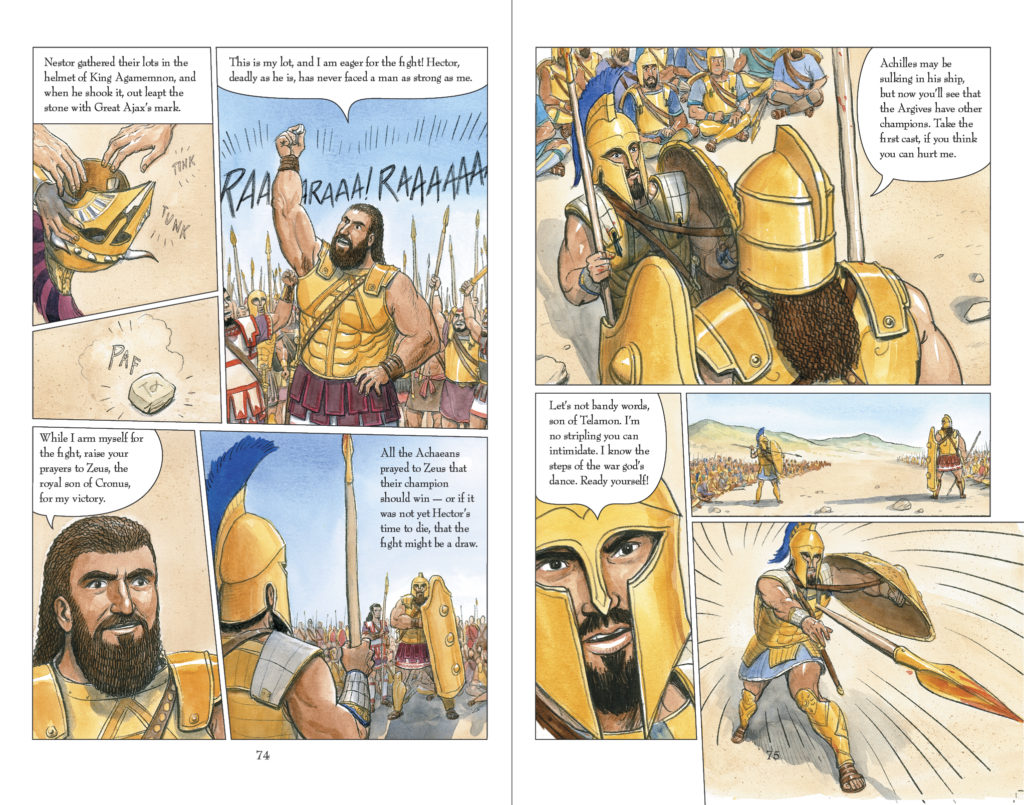

It is with Homer’s epics that Hinds truly shines though, breathing life into tales that sometimes seem to be as old as time itself. From the siege of Troy and the kidnapping of Helen to the colorful adventures that befell gods and heroes like Achilles and Odysseus, so much of it has seeped into our collective consciousness that these morals, victories, and tragedies often risk losing their potency. Hinds creates sweeping panoramas, windswept oceans, and intimate panels of watercolors that range from the merely pretty to the often awe-inspiring, to make sure the stories still seem alive. They also give his work a kind of emotional heft that appeals to readers far older than the teenagers he claims to address.

The Iliad and The Odyssey are dense works, crowded not just with a host of major and minor characters, but chock full of metaphors and parables that have been argued over and dissected for centuries. The scale is staggering when one considers that The Iliad alone is a poem that extends over 16,000 lines. Hinds condenses them into narrative comics that rarely go beyond 250 pages, offering his readers annotations, character guides, recommendations for scholarly readings, and explanations for his edits.

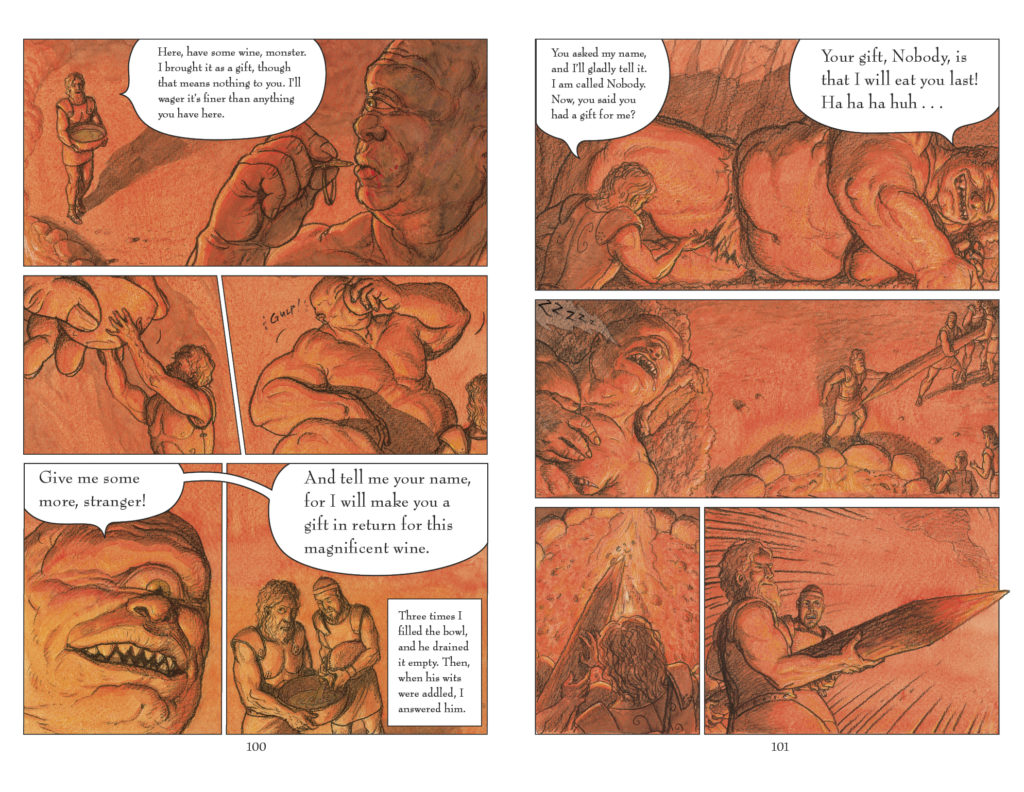

Much can also be said about his use of color. When Odysseus is trapped by the Cyclops, for instance, the panels are awash in orange, presumably to reflect the claustrophobic heat of the cave. Out at sea, hues of blue start to dominate, representing the vastness of the ocean that can be beautiful as well as empty depending upon whether one is a witness or a homesick soldier desperate for a sight of land.

An interesting thing about both epics is how they move effortlessly from personal to political, and from humankind to the divine. This makes for great visual cues, of course, because few illustrators will shy away from an opportunity to render the Cyclops Polyphemus, or his father Poseidon, God of the Sea, or the Scylla and Charybdis that Odysseus and his men must navigate between.

Conversely, holding on to that narrative thread becomes difficult because Homer uses these devices as moving parts of a larger whole. The reader can’t forget that the ultimate goal is Ithaca, where Odysseus has a wife and son waiting for him, along with armed suitors in no mood to let him take control after decades of being presumed dead. Hinds moves it along, allocating just the right amount of space to each adventure while employing flashbacks to remind readers of parallel storylines. It makes for a work that is gritty as well as moving.

Between 1998 and 2013, the Boston Public Library instituted a Literary Lights for Children Award, honoring outstanding authors as part of a program introducing young readers to great works of literature. Hinds was an honoree alongside other notable names such as Neil Gaiman, Rick Riordan, Brian Selznick, and M.T. Anderson. I thrust copies of Hinds’s work into as many young hands as I can because the classics deserve to be known at least as well as animated sitcoms. Also, because a world that roots for the right Homer is a smarter one.

![[REVIEW] HOW DOES A GRAPHIC NOVELIST MAKE MARCEL PROUST RELEVANT AGAIN?](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/proust2-150x150.jpg)