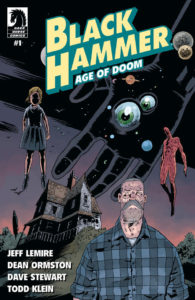

Black Hammer: Age of Doom #1

Writer: Jeff Lemire

Artist: Dean Ormston

Colors: Dave Stewart

Letters: Todd Klein

Publisher: Dark Horse

A review by Jim Allegro

Jeff Lemire’s Black Hammer series takes a generational turn in Black Hammer: Age of Doom. Released on April 11 by Dark Horse Comics, the first issue of the second season of this Golden Age allegory focuses on our new, young protagonist, Lucy Webber, who picks up the cosmic hammer after the death of her father. Lucy’s struggle to lead the collection of aging heroes out of the dimension in which they are trapped provides fertile ground for the core themes that characterize Lemire’s body of work, such as the relationship between identity and memory, a sense of place, and the line between real and not real.

Jeff Lemire’s Black Hammer series takes a generational turn in Black Hammer: Age of Doom. Released on April 11 by Dark Horse Comics, the first issue of the second season of this Golden Age allegory focuses on our new, young protagonist, Lucy Webber, who picks up the cosmic hammer after the death of her father. Lucy’s struggle to lead the collection of aging heroes out of the dimension in which they are trapped provides fertile ground for the core themes that characterize Lemire’s body of work, such as the relationship between identity and memory, a sense of place, and the line between real and not real.

But, above all, this is a comic about aging, family, and loss. Black Hammer is the story of growing old. The impotence of old age is clear in the opening panels of Age of Doom, in which Barbalien, Golden Gail, and the other heroes of a bygone era sullenly rail at the fact that they stuck on a farm in a small town that does not know heroes. Their paralysis is a parable for our aging parents and grandparents. They are our Baby Boomers, who, with the Cold War over and their work done, i.e., defeating the anti-God, flail against the demons of their pasts as they quest for meaning in a society that no longer knows them.

Lucy is key to this search for meaning. The all-new Black Hammer is our Millennial. Diverse, confident, and impatient for change, this young black woman embodies hope for the future. She knows why they are stuck on the farm and how to get off. But, before she can offer that information, she is transported against her will to a strange world. Rescuing your elders from irrelevance is hard, maybe impossible, she learns as she rushes to escape the broken heroes, punk rock malcontents, weird bartenders, and others who populate this eerie maze. Her trial embodies all of our struggles to escape youth and assume the responsibilities of adulthood. Even if it means confronting what I suspect is the lesson of Lemire’s story: coming into your own means being more potent than the loving adults who raised you.

Lucy is key to this search for meaning. The all-new Black Hammer is our Millennial. Diverse, confident, and impatient for change, this young black woman embodies hope for the future. She knows why they are stuck on the farm and how to get off. But, before she can offer that information, she is transported against her will to a strange world. Rescuing your elders from irrelevance is hard, maybe impossible, she learns as she rushes to escape the broken heroes, punk rock malcontents, weird bartenders, and others who populate this eerie maze. Her trial embodies all of our struggles to escape youth and assume the responsibilities of adulthood. Even if it means confronting what I suspect is the lesson of Lemire’s story: coming into your own means being more potent than the loving adults who raised you.

The artwork of Dean Ormston’s penciling and Dave Stewart’s coloring reinforces this melancholy point. The confusion and disappointment arising from a mismatched family trying to adjust to a generational changing of the guard is clearest from the long shadows often cast by the characters onto each other’s faces and bodies. These are self-absorbed figures that do not see each other for what they are, and, as such, they do not see Lucy, whose face and figure are almost always impeded in her initial meeting with her dead father’s colleagues. Only when she is alone in the bizarre maze, at the staging ground of her own awakening, do we catch a full glimpse of our protagonist. And, even then, the gloom still trails her.

And, the same shadows no longer impede our aging superheroes in the last act. The fact that the first issue of Lemire’s and Ormston’s Black Hammer: Age of Doom glimpses our heroes coherent and calm, banding together as surrogate kin intent on escaping this dimension, testifies to the power of youth and change embodied by Lucy’s character. I have every confidence that this awkward family will surmount whatever obstacles await them as they struggle to accept the inevitability of the life cycle. Lemire’s stories are often brooding, and haunting, but they are not without hope.

Verdict:

Buy It! The Black Hammer universe remains fertile ground for Lemire’s homage to Golden Age comics.

![[REVIEW] THE POWER RETURNS IN ‘MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE: REVELATION’ PART ONE](https://geekd-out.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/D719EA5C-86A4-48BC-A3A2-6C89B9A0676E-150x150.jpeg)