The 1960s were the heyday for horror when it comes to Hammer Film Productions. They practically became a household name, at home in Britain and abroad, by breathing new life into a stagnating genre.

But it wasn’t just their mainstay franchises, Frankenstein and Dracula, which earned them this reputation. The studio was a workhorse from the late-’50s through the ‘60s, pumping out film after film with surprisingly consistent quality. They would shoot movies back-to-back using the same sets, casts, crew and costumes while still creating markedly individual works. They worked on shoestring budgets and tight timelines to maximize profits, and for the most part it also seemed to maximize the creativity in the various productions.

Of course, a production style like that could never last.

Eventually their own output and influence became a detriment to them. How could you make the fourth Mummy film interesting? (Or the seventh Frankenstein? Or the ninth Dracula?) How could you compete with British and American films coming out that were inspired and invigorated by your own innovations? When you build an entire style of sexual subtext and creative gore, what do you do when laxer ratings standards allows the subtle to become overt?

The answer, unfortunately, is carry on for about another ten years with diminished results and only a small number of standouts.

Before moving on to those final years I’d like to spend this article and the next discussing the last remaining standouts of those golden years. Next article will discuss Hammer’s work adjacent to or outside of the horror genre, but for now I’m going to highlight some notable horror titles.

As mentioned before, with the amount of work churned out it was necessary for Hammer to have a dedicated and reliable cast and crew. A few of these films star or feature our boys Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, while other Hammer mainstays like Oliver Reed, Michael Ripper, Patrick Troughton and Barbara Shelley make appearances. Behind the scenes, Terence Fisher and producer Michael Carreras were responsible for some of the best — and worst — entries in this.

Hammer’s horror influence reaches far beyond their incarnations of Dracula and Frankenstein. Hammer reinvented, reinterpreted and created some truly influential creatures and premises. Some of them more influential or more successful than others, but all of them worth at least a passing glance.

The Mummy (1959)

This October was only the second time I had seen Hammer’s version of The Mummy. My first time through I had been fairly underwhelmed. It seemed as if the story stopped and started in fits and the whole production paled in comparison to Horror of Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein despite sharing the same leads and reinterpreting a classic monster tale. For some reason I built it up in my head that it was going to be a chore to sit through this time around.

I couldn’t have been more wrong the first time through.

Lower expectations surely helped, but The Mummy is a surprisingly slick and fleet film, even in comparison to other Hammer films. There’s only one flashback slowing the pace, while still remaining compelling, and the rest of the film has almost no fat on its bones. As is the way with Hammer, there are a small number of sets, with only the archaeological dig and the flashback taking the action away from England. And of course, by this point, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee were experts at their respective archetypes.

Cushing’s strengths are really highlighted in this role, arguably even more than his work as Baron Frankenstein or Dr. Van Helsing. As John Banning, archaeologist and prospective mummicide victim, he’s relegated to the Bland Leading Man role that most Hammer films — or horror films in general — feel like they need to have. His character doesn’t even get much of a twist or particularly standout dialogue. There’s nothing dark or obsessive to cling to like Baron Frankenstein and he’s not an expert of the occult like Van Helsing. Which is why it’s so impressive that Cushing remains captivating as the lead. His intensity comes off as warm and, as usual, he throws himself into every action beat possible.

It helps when he has someone like Lee to work against. By virtue of height and presence alone, Lee is an intimidating presence. Even with his face bandaged and mud-caked, frozen like stone, his eyes express more than most actors can manage. An eye-roll or a purposeful stare clearly expresses conflict or anger or dispassionate bloodlust. His power as he slams through the door of a house and deliberately stalks after his victim is truly startling. If Lee’s Mummy wasn’t a large influence on Halloween’s Michael Myers or Friday the 13th’s Jason Voorhees I’d be truly surprised.

The Mummy is absolutely a film worth of standing alongside the Hammer classics. Its production design is simple and unique — the murky swamp is a particularly original standout — and is a perfect example of Hammer’s strengths and ingenuity.

The Curse of the Werewolf (1961)

Oliver Reed was a fantastic actor who had a great career that I’d argue should have been even greater. Reed had the screen presence of a leading man, the dark and brooding looks of a classic silver screen heel, and almost supernaturally intense eyes. Reed ended up becoming a Hammer mainstay throughout the ‘60s, featuring in Captain Clegg, The Pirates of Blood River, The Scarlet Blade, Paranoiac and The Damned, among others. There’s no mystery why Hammer would continue to use Reed, just as there’s no mystery why Reed had a very successful career post-Hammer.

It’s just unfortunate that he has to start in The Curse of the Werewolf.

Werewolf stories are among my favourite when it comes to classic horror monsters. There’s something especially tragic about a good person being cursed to become their feral id. It’s a very basic and effective tale that’s been told extremely well and frustratingly poorly. While The Curse of the Werewolf has a lot in it to like, it leans closer to the latter category.

The story plays out more like a fairy tale than other versions I’ve seen. There’s an evil Marques, an abused beggar, a mute servant. The origin of a werewolf bloodline plays out like a Spanish legend that would be told to children to frighten them. And that part’s actually fairly compelling. The problem is the length. There’s so much backstory and preamble before Oliver Reed’s Leon shows up as an adult that we barely get to spend any time with him. If a worse actor than Reed had been playing the role the whole film may have been a disaster. As is, the finale seems to come and go too quickly for us to even get a good read on it.

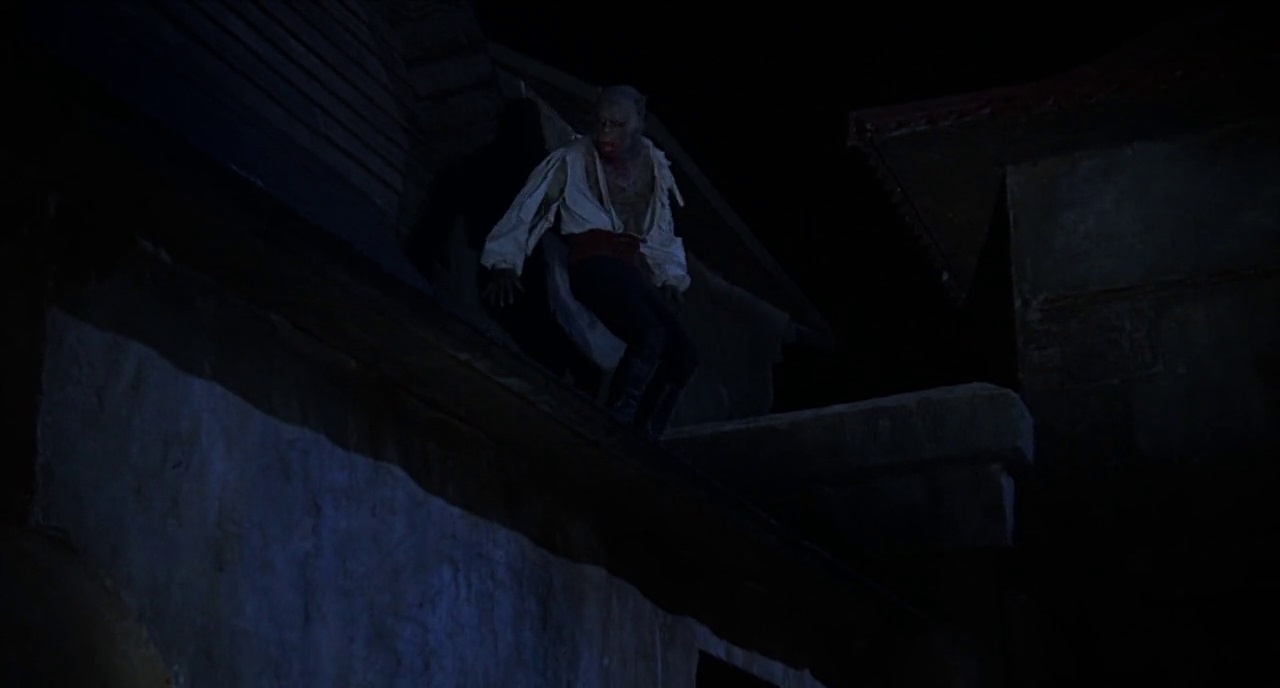

When it comes to the production design, The Curse of the Werewolf is top notch. It spans decades, different counties and towns, without ever showing its limited budget. The finale, with a transformed Leon jumping and climbing across rooftops, is solid and thrilling. The creature effects aren’t the best werewolf design put to film but they’re serviceable and sold aptly by Reed’s performance.

I just wish we’d gotten more of it. Even 15 minutes less backstory and 15 minutes more of a full-grown Leon would have helped with pacing, balance and characterisation. Taken on its own I’m not surprised that there were no sequels. The movie wraps itself up in a tragic, self-contained manner — not that that’s ever stopped a Frankenstein or Dracula movie — but most importantly there just wasn’t enough life in the overall production. What little thrills come from The Curse of the Werewolf unfortunately come too little too late.

The Phantom of the Opera (1962)

This film has always had a weird feel to it. Like everyone involved was just going through the motions and adapting The Phantom of the Opera because it was expected of them. Which isn’t to say that the everyone phoned-in their work — Terence Fisher, as usual, does fine work as director — but something about the story, structure and execution feels by-the-numbers.

This adaptation keeps the broad strokes of the original novel while loading it up with some solid Hammer details. Set in 1900 London, this Phantom is a vengeful and almost righteous figure, most of the controversial deeds in the film are pawned off to his caretaker/minion, The Dwarf. It was an odd decision, splitting what should have rightfully been one role with one set of motivations and actions into two different parts. Due to that decision neither Ian Wilson’s Dwarf (which is all he’s offensively credited as) or Herbert Lom’s Phantom feel complete. The sympathetic Phantom was an artist, wronged by Michael Gough’s amusingly caddish Lord Ambrose, disfigured and doomed to live life secluded from society. The Dwarf, however, does all the killing and messing up for the both of them, making nonsensical decisions and giving us no insight into what makes him tick.

Apparently Cary Grant was interested in playing the lead role in Hammer’s adaptation of Phantom. Whether this role was the Bland Leading Man or the Phantom himself isn’t really confirmed, but if it were the Phantom then it would explain the odd choices in the script. I can see why they’d want to make Grant more heroic and pass the more horrific duties onto a side character. Unfortunately, this is a bad decision that hobbles the film. Ultimately what The Phantom of the Opera needed was another pass at the script. Leaving aside the issues with the Phantom’s characterisation, the finale and the Phantom’s heroic death are both oddly staged and way too broadly drawn. It feels like they shot a Wikipedia summary of a finale instead of an actual script.

Despite all of that it’s still worth a look. The Phantom’s lair, while underseen, looks great. And, as mentioned above, Fisher does a solid job again behind the camera. The off-kilter cold open is really effective and the freeze frame on the Phantom’s eye leading into the credits is the scariest his lame mask looks throughout the entire film. Lom does a solid job with what he’s given, but the script never lets him do anything interesting, which is a shame.

The best reason to watch the film is Michael Gough. It was nice seeing him pop up in a Hammer film again, this time getting to be as slimy and evil as he can while clearly relishing every second of it. He’s fantastic and his lack of an actual comeuppance is another big deficit in the final act of this film.

The Gorgon (1964)

When I think of classic Hammer horror films The Gorgon is one of the first ones to pop into my head. I’m actually surprised that it was made in 1964 because it feels like it was made alongside Horror of Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein.

The Gorgon is another film starring Cushing and Lee, with Cushing in full-on asshole mode while Lee plays the wise old expert role which he rarely gets to bust out. Working with them is one of the most solid supporting casts in any Hammer film. Barbara Shelley, Richard Pasco, Michael Goodliffe and Patrick Troughton (who also had a hilariously short-lived appearance in The Phantom of the Opera as The Ratcatcher) and there isn’t a single weak-link in the bunch.

Another great and unique touch to the film is updating a Greek myth for the basis of its story and monster. The imagery and destructive power of the Gorgon is so good that it fits perfectly alongside the likes of the Mummy or Werewolves or Vampires. It was a smart decision to adapt that creature to the Hammer pantheon.

The story cruises along at a solid pace with enough action beats along the way to keep us interested, and enough variety within those beats to keep them unique. The Gorgon doles out its revelation of the title monster in perfect chunks leading up to the full reveal. It doesn’t fall into the trap of revealing the monster too late for us to really care (The Curse of the Werewolf) or too early, giving its subsequent appearances diminishing returns. The design of the creature itself is good and understated, working extremely well in reflection and from a distance. The snakes in the hair come off as kind of plastic-y and goofy in some of the close-ups, but not enough to ruin it.

By the time we get to the finale there are three characters converging on the creature with similar yet opposing goals. It’s extremely solid writing. As usual Cushing throws himself into his action scene, sword-fighting Pasco’s Paul Heitz with aplomb.

There’s also some honest enjoyment at seeing a film end with Lee’s character being the only one who doesn’t die.

The Gorgon is great and belongs up at the top of the Hammer Canon alongside Horror of Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein. Easily one of the best works from all involved.

The Plague of the Zombies (1966)

The amount of influence The Plague of Zombies has had on popular culture can’t be undersold. George A. Romero considered it an influence while making Night of the Living Dead and its sequels, which in turn laid the foundation for the majority of zombie media you see to this day. So it’s an odd combination of influential and underseen, which is something that should be corrected.

A small English village is a standard Hammer location — so much so that the film was shot back-to-back with The Reptile using the same set — and Plague makes good use of it. When André Morell’s Sir James Forbes and Diane Clare’s Sylvia Forbes arrive in town the place feels lived-in. Plus they’re accosted by a gang of fox-hunters. More movies should have evil fox-hunters.

Plague is relegated to only a few sets but the film makes the most out of them. One in particular, the “abandoned” mine, is used particularly well for a solid jump scare and the fiery finale. Overall the film uses trippy imagery and dream sequences much more than Hammer films had prior to this. Not only is it effective but it sets it apart from its contemporaries.

The cast of Plague does well, with Morell and John Carson as the nefarious Squire Clive Harrison (how great is that name?) especially standing out. When we first see the zombies — dead villagers turned undead using Haitian voodoo — their grey complexion and pale, white eyes stand out in a shocking way. The finale downplays their effectiveness, these aren’t the brain-eating and flesh-tearing zombies we’re used to, and instead focuses on Squire Clive Harrison as the nemesis to beat. It works well. What we lose in being visually frightened by the zombies we more than make up for with the fiery set piece.

The Witches (1966)

The Witches is an interesting, if not entirely successful, departure from the regular Hammer house style. The present day setting, occult weirdness and rustic countryside locations put it more in the vein of folk horror. Joan Fontaine’s fantastic lead performance is also the type of barely-held-together paranoia and mania we’d expect from a Hitchcock protagonist. So The Witches really sets itself apart from what we’ve come to expect from Hammer horror.

I believe a lot of that has to do with the film’s writer, Nigel Kneale. I’ll discuss him further next week in Part 4, but Kneale is the creator of the Quatermass films and a prolific screenwriter who was tasked to adapt The Devil’s Own by Norah Lofts. He did an admirable job, turning in an unsettling, slow-burn thriller. Kneale said his work was changed when they filmed it, but he always comes off as a little curmudgeonly in interviews, so it’s hard to tell to what extent that’s true.

What the filmmakers definitely got right was the atmosphere. As Fontaine’s school teacher character enters the rural village we see everything from her perspective. When strange things start occurring — voodoo dolls, mysterious deaths, etc. — and Fontaine investigates further we experience the uneasy, feverish feelings of madness that she’s experiencing as well.

The Witches has a great build-up throughout its runtime. Enough intrigue and weirdness happens at a steady clip to keep us as off-balance as the lead. Where it falters is the finale. It’s weird and abrupt and tonally inconsistent with the rest of the film. If they had made the final coven ritual even more over the top it may have been enough to make it an interesting juxtaposition, but as is the finale just doesn’t play well. And the final scene is so quick and cheery that it seems like an odd joke they tacked on.

Ignoring the limp ending, The Witches is definitely worth watching. Kneale’s writing is always great and Fontaine is fantastic as the lead. While it doesn’t stick the landing, this movie deserves to be mentioned, if not alongside the best of Hammer, then definitely among the most interesting.

The Devil Rides Out (1968)

There are few things I love more than a good Satanic Cult story. It’s a great excuse for all sorts of ridiculous stuff to happen, which is evident in The Devil Rides Out. Christopher Lee is our hero, playing the goateed Duc de Richleau, and it’s nice to see Lee in a purely heroic role. His imposing figure makes him perfectly authoritative. You believe some crazy shit is going down by how shocked and appalled he is at finding a basket full of chickens in the closet.

Trusty Hammer helmer Terence Fisher was behind the camera on this one and it shows. The movie immediately gets in on the action with Lee and his dumb, useless friend Rex rescuing their friend Simon from the devil-worshiping cult he’s gotten himself involved with. FIsher’s steady hand steers the proceedings enough that the movie glides by with no real speed bumps or dull moments.

He’s helped along in this endeavour by the script, an adaptation of Dennis Wheatley’s book, by Richard Matheson. Matheson is a well-deserved horror and sci-fi icon and he delivers in this script, knowing exactly when to pace the set pieces and exactly how goofy the dialogue can be before we laugh or roll our eyes.

Lee’s supporting cast are all passable-to-fine except for two standouts. The first is Sarah Lawson as Marie Eaton. She doesn’t play much of a part in the proceedings until later on but Lawson is captivating. She plays a multitude of layers throughout the film, going from down-to-earth to terrified to possessed to entranced. And she makes it all seem natural. The other standout is Charles Gray’s Mocata. The veteran actor is a great counterpart to Lee and he looks like he’s having a blast as the hypnotic cult leader.

Some of the final act effects don’t hold up, some compositing and wirework showing around the seams, but the acting and direction help to gloss over any rough patches. There are also some effects which still work surprisingly well despite the age and hokiness. Also, like The Gorgon, it was nice seeing Lee play an undeniable hero.

Plus, Baphomet gets blown up with a thrown crucifix. How could you not love that?

The Vampire Lovers (1970)

The Vampire Lovers signals a change of pace for Hammer film going forward. At this point Hammer had been head of the class in the genre for over a decade. But times were changing and their competition was spurned on by Hammer’s seductive flirting with the limits of the ratings board. Movies had gotten gorier and more sexually explicit and Hammer decided they needed to keep up in order to remain relevant in the b-movie marketplace.

They had mixed results, unfortunately.

The Vampire Lovers is about as successful as they got while trying to stay ahead of the curve and “shocking”. It’s the story of lesbian vampires told in a fairly standard, Hammer way. Luckily we have Peter Cushing on-board to help ease the transition from class Hammer horror to the new, lesser standard the ‘70s would entail. Cushing is a supporting character, a kind of counterpart to this movie’s version of Van Helsing, Douglas Wilmer’s Baron Hartog. Hartog gets a solid action beat near the beginning, and some spooky imagery with the shrouded vampire, but his narration kills a lot of the tension and we get a shorter, unnecessary recap of the opening later on in the film.

But the stars of the film are Emma, played by Madeleine Smith, and Mircalla Karnstein, played by Ingrid Pitt. They both do a pretty good job. Smith doesn’t get much to do besides play the victim but she manages to wring some actual fear out of the situation. Pitt is perfectly cast as the seductive Mircalla, easily slinking her way into situations that allow her to feed off of innocents. The downside is it makes literal what has always been arguably subtle in previous vampire tales. Someone who is afraid of Christian norms, who enters your room at night to nuzzle your neck and turn you “impure”, is fairly blatant without exactly broadcasting it in big neon letters. The Vampire Lovers takes away the thin layer of pretense and doesn’t really replace it with anything more interesting than random nudity.

Overall it’s skillfully shot and has some striking visuals. The story is a slight letdown though, never reaching for much beyond the surface level when there’s a lot you could sink your teeth into when it comes to the concept of lesbian vampires.

The Curse of the Other Movies You Should Watch

Obviously the standard-bearer when it comes to werewolf cinema is 1941’s The Wolf Man, but the tragic story of werewolves easily lends itself to drama. The Wolfman from 2010, starring Benicio Del Toro and Anthony Hopkins, is a solid remake of the ‘41 film with more than a little bit of Hammer influence flowing through it. There’s also a great, underrated Canadian film from 2000 called Ginger Snaps which takes a decidedly feminist view of lycanthropy, something so smart yet seemingly obvious that it’s a wonder it hasn’t become the go-to for werewolf stories.

I mentioned folk horror earlier in regards to The Witches, but even The Plague of the Zombies has a bit of that flavour. Check out The Wicker Man (the 1973 version, of course) and 1970’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw for more of that uneasy, creeping dread set against the backdrop of the English countryside. If satanic cults are your thing — which, why wouldn’t they be? — there’s a fantastic movie starring Warren Oates and Peter Fonda called Race With the Devil. If you want a movie where the leads are being pursued by a satanic cult while they try to outrun them in an RV then there literally is no other movie for you.

When it comes to the remaining films in The Mummy series they all range from skippable to passable. Losing Terence Fisher, Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing for the remainder of the films was basically a death blow, with only 1971’s Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb attempting to rise above that. The Vampire Loves was the first film in “The Karnstein Trilogy” and probably the best. The sequel, Lust for a Vampire, is a solid b-movie setup executed poorly. The third film, Twins of Evil, is watchable if you’re into the more overtly lurid and campy direction Hammer eventually took.

Coming Up in Part 4 . . .

Hammer Film Productions became defined by its horror output, and for good reason, but they continued to put out films in a wide range of genres and styles. Next time we’ll cover a few of the standouts.

In Case You Missed It . . .